What the Last Year Taught Us About Low-Volatility ETFs

Are they living up to expectations?

A version of this article previously appeared in the June 2021 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of Morningstar ETFInvestor by visiting the website.

The past year has been a reality check for investors holding low-volatility exchange-traded funds. While most of the global market sprinted back from the depths of the coronavirus-driven sell-off, low-volatility strategies chugged along at a slow jog. They appreciated in value but failed to keep pace with the market’s aggressive tempo.

The numbers paint a pretty stark picture. IShares MSCI USA Minimum Volatility Factor ETF USMV, which has a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Silver, trailed the S&P 500 by 25.9 percentage points over the 14 months from April 2020 through May 2021. Similar deficits were observed for other low-volatility strategies focused on foreign developed and emerging markets.

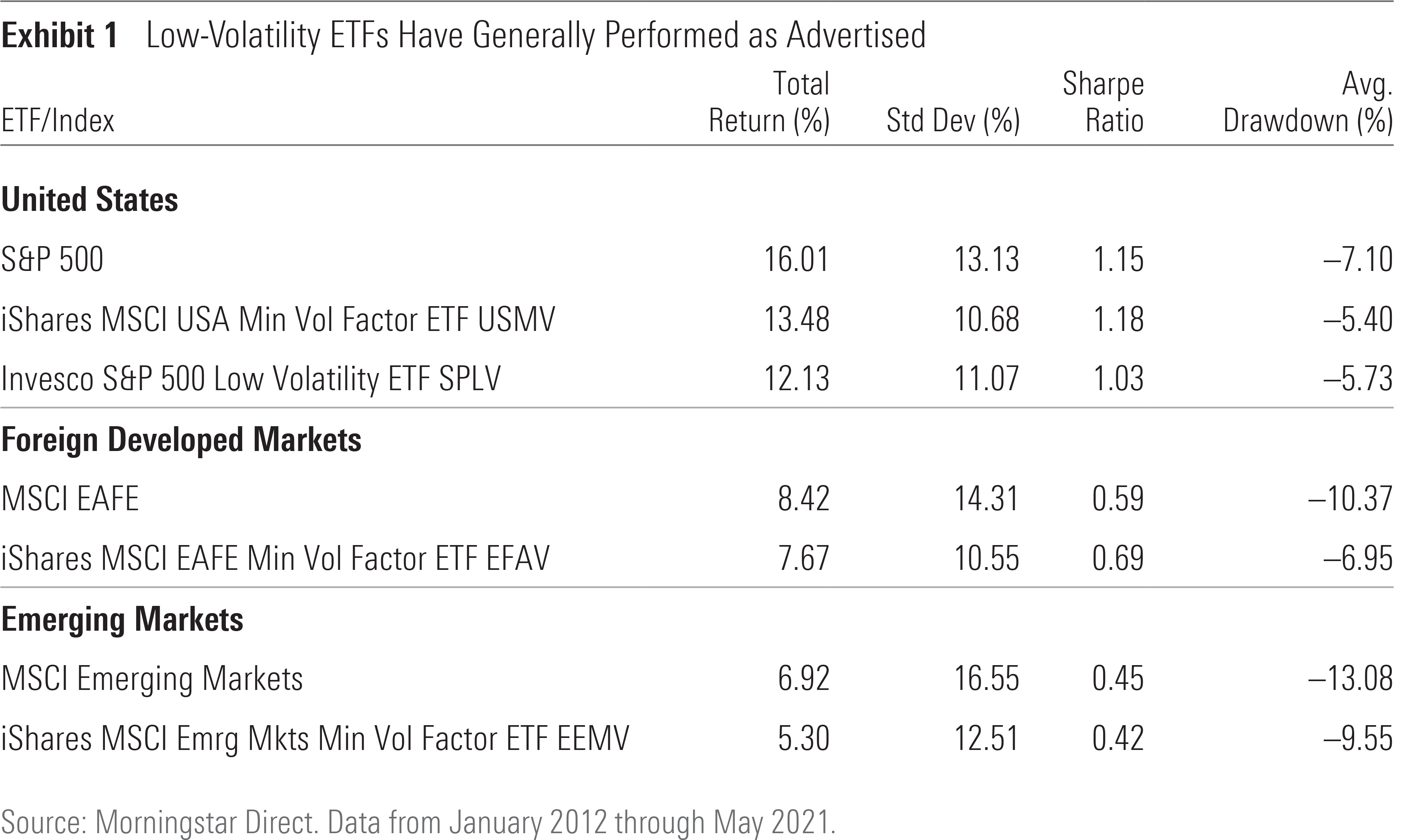

Over the long run, low-volatility strategies have proved effective at cutting back on statistical measures of risk. But they differ from many other strategies in that they aren’t designed to beat the market. Instead, the expectation is marketlike total returns with less risk, which sets them up for better risk-adjusted performance. Cutting back on risk may make them an easier stock strategy to stick with, but they come with trade-offs and are by no means a substitute for cash or bonds.

There’s No Free Lunch

Low-volatility strategies underreact to market movements, be they large upward moves or deep drawdowns. They typically provide some downside protection when the market goes through a downturn. The index USMV tracks, the MSCI USA Minimum Volatility Index, has largely delivered on that expectation. It beat the market when the dot-com bubble burst in mid-2000 and again eight years later when the market collapsed during the 2008 global financial crisis.

There is a price to pay for that benefit. Low-volatility strategies typically underperform during bull markets. USMV’s benchmark lagged the market during the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, the first two years of the recovery from the global financial crisis, and most recently during the rebound from the coronavirus-driven sell-off.

That pattern isn’t limited to the United States. The same expectations and performance apply to low-volatility strategies targeting foreign stocks. Two examples on the menu of Morningstar Medalists are Silver-rated iShares MSCI EAFE Minimum Volatility Factor ETF EFAV and Silver-rated iShares MSCI Emerging Markets Minimum Volatility Factor ETF EEMV. Like USMV, their target indexes held up better during the financial crisis and underperformed during the rebound.

Those trade-offs are the main way that low-volatility funds differ from their respective market, and the pattern is reflected in the historical statistics for these strategies. Exhibit 1 shows that standard deviations have been lower and drawdowns, on average, have been shallower.

Low Risk Doesn’t Mean No Risk

Long-term averages indicate these strategies have lived up to their billing. However, they are far from perfect, and long-term averages may hide short periods of undesirable performance that investors should expect but would no doubt prefer to avoid.

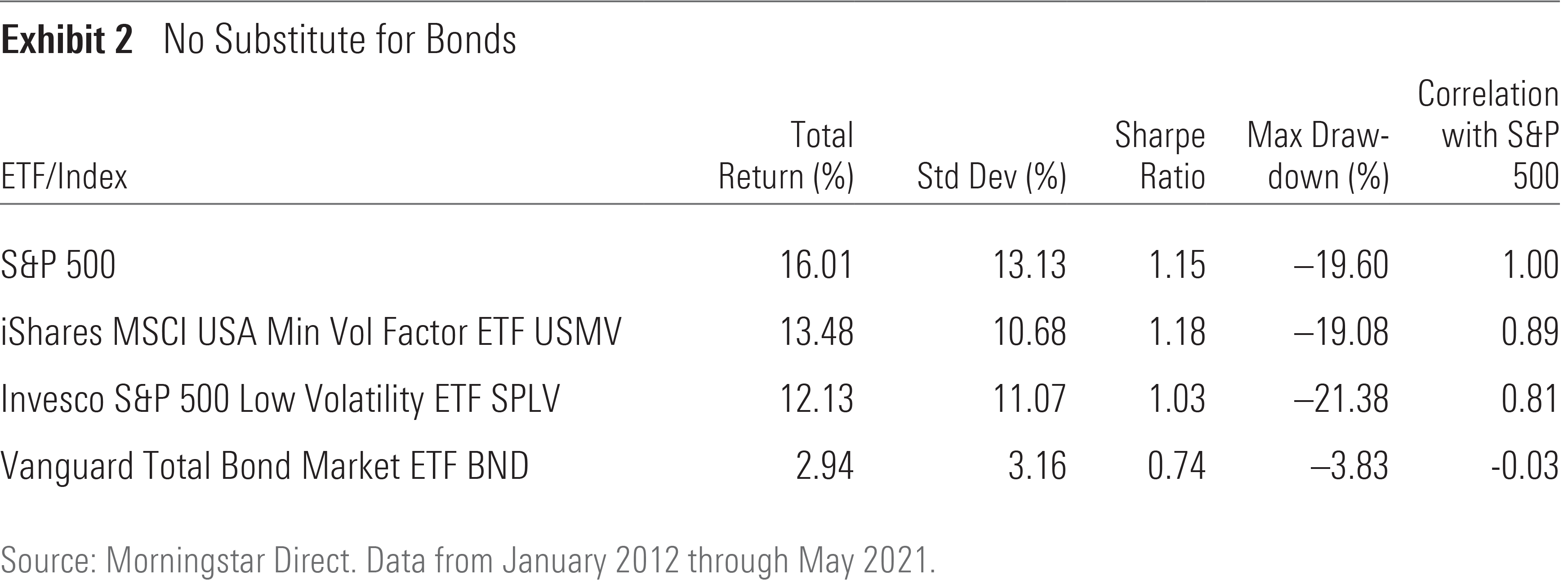

One such instance occurred during the pandemic sell-off. Low-volatility strategies should have provided some downside protection, but Invesco S&P 500 Low Volatility ETF SPLV and USMV did not. The S&P 500 declined by 33.8 percentage points between Feb. 6 and March 23, 2020. USMV shed 33.2 percentage points, while SPLV lost more than 36. Both failed to deliver when it mattered most.

Even when they successfully provide downside protection, low-volatility funds are still subject to substantial declines. For example, the S&P 500 lost 51% between October 2007 and February 2009, as the financial crisis put the global economy on ice. The index that USMV tracks declined 41% over that same period. It outperformed the market but still incurred a fairly sizable drawdown.

Circumstances like that are a reminder that USMV, SPLV, and their overseas counterparts are still fully invested in stocks. By design, they take some risk off the table, but they are still quite volatile and are not suitable substitutes for more stable assets like bonds and cash. Exhibit 2 shows the standard deviations of the S&P 500, USMV, SPLV, and Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF BND over the past 10 years. USMV and SPLV had lower standard deviations than the market, but they were nearer to the market than a broad basket of investment-grade bonds.

Rare Events With Big Consequences

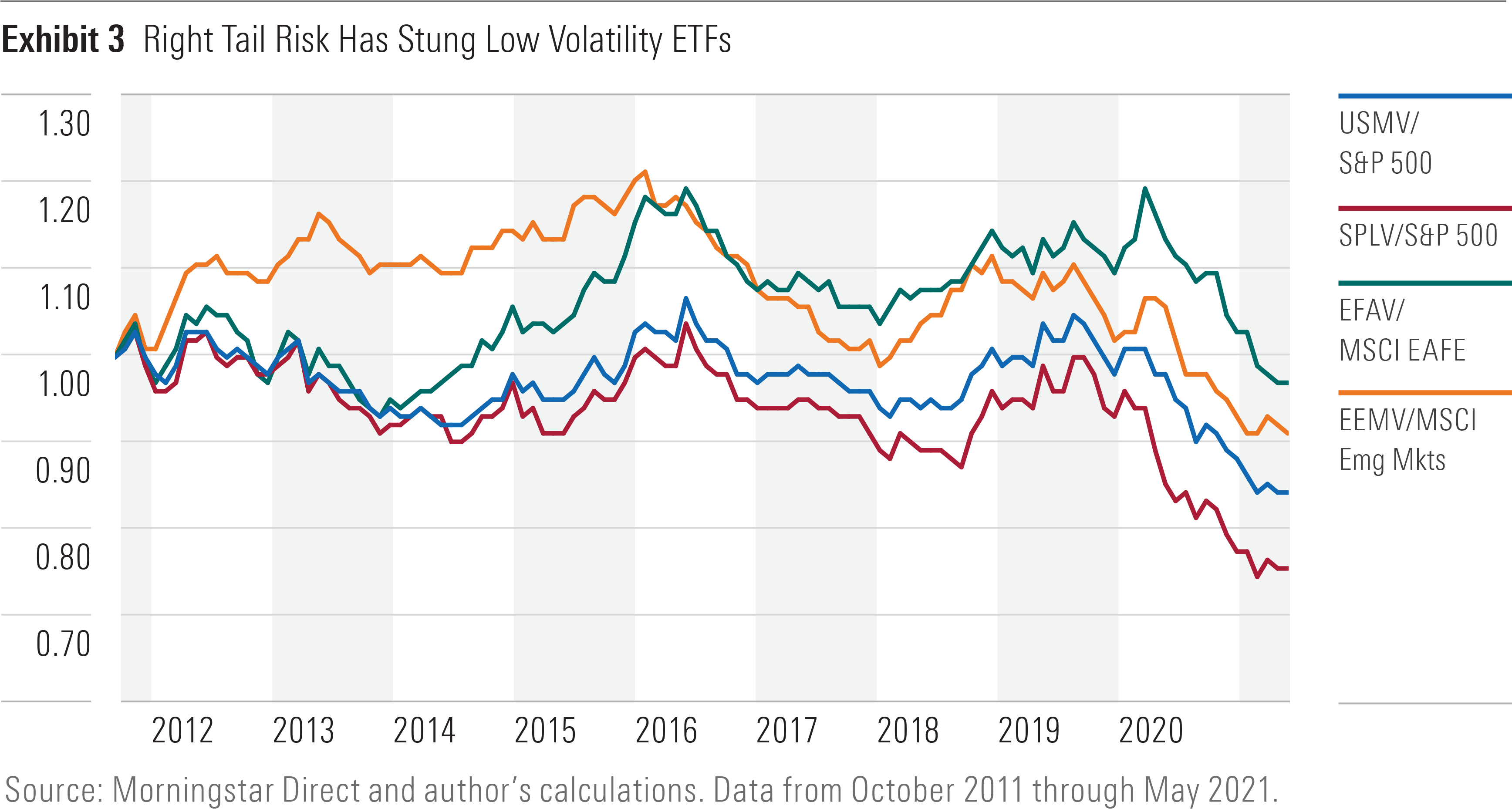

Low-volatility ETFs hummed along as expected for years leading up to the coronavirus pandemic. Periods of outperformance aligned with market dips, while lackluster returns were tethered to strong rallies.

Long-term total returns were almost too good to be true. USMV, EFAV, and EEMV earned better total returns than their respective markets from their launch in October 2011 through March 2020. USMV beat the S&P 500 by 11 basis points per year, EEMV outperformed the MSCI Emerging Markets Index by 61 basis points annually, and EFAV led the MSCI EAFE Index by a whopping 1.9 percentage points annualized. The advantage was greater overseas because foreign markets were volatile and performed poorly by historical standards.

But eventually, all good things come to an end. Starting in April 2020, most global markets went on a tear. The S&P 500 turned in one of its strongest 12-month total returns over the ensuing year. Low-volatility ETFs, with their preference for sluggish stocks, were left in the dust.

The fallout has been nothing short of incredible. USMV, EFAV, and EEMV underperformed their respective markets so severely that their long-term outperformance reversed to a deficit. USMV was among the hardest hit. Over the 14 months from April 2020 through May 2021, its 11-basis-point-per-year advantage decayed to a 2.2-percentage-point annualized performance shortfall.

The relative growth chart in Exhibit 3 illustrates their tremendous fall from grace. It plots the growth of four low-volatility ETFs relative to their respective markets. An upward-sloping line indicates an ETF is beating its market, while a downward slope represents underperformance. All four experienced modest episodes of over- and underperformance during their first eight years.

All Is Not Lost

There is still a lot to like about low-volatility strategies, so long as expectations are understood and they are used with a long-term perspective in mind. The long-term risk-adjusted performance of these strategies is where they shine brightest and underpin USMV, EFAV, and EEMV’s Silver ratings.

Risk and return are often linked in financial markets, but the connection between the two isn’t defined by rigid law. These strategies should continue to eliminate a decent chunk of risk from the market without sacrificing too much return. Investors will have to deal with lagging when the market is doing well. That’s the price for cutting back on risk.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Morningstar, Inc. does not market, sell, or make any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/24UPFK5OBNANLM2B55TIWIK2S4.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_29c382728cbc4bf2aaef646d1589a188_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)