U.S. Oil & Gas Producers Could Face $4.8 Billion in Methane-Related Charges, Study Claims

Trouble ahead for Diversified Energy, ConocoPhillips, Occidental, and CRC?

Curbing global warming is hellishly difficult, but one way is to slash emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas that is about 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Methane emissions are on the rise and, according to a new study of satellite data, are more than 10 times larger than companies report. Under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, that could lead to higher-than-expected fees for a range of U.S. oil and gas companies, including Occidental Petroleum OXY and ConocoPhillips COP.

New Efforts to Slash Methane Emissions

At the COP28 climate summit, 50 oil companies representing nearly half of global production, including ExxonMobil XOM and Saudi Arabia’s Aramco, pledged to reach near-zero methane emissions and end routine flaring in their operations by 2030.

In addition, the Biden administration unveiled rules to crack down on releases of methane by U.S. oil and gas companies. They are part of a promise that nations including the United States made two years ago on slashing emissions by 30% from 2020 levels by 2030.

Among other things, the Environmental Protection Agency would require oil companies to monitor for leaks and use remote sensing to detect large methane releases from so-called super-emitters.

Inflation Reduction Act Methane Fees Kick In

Separately, the Inflation Reduction Act, the landmark law that promotes the use of renewable energy, imposes a charge on methane emissions from facilities required to report their greenhouse gas emissions to the EPA. The charge starts at $900 per metric ton of methane, increasing to $1,500 after two years. It is the first time the federal government has directly imposed a charge on greenhouse gas emissions.

Efforts to hit the 1.5-degree Celsius global warming target set by the historic 2015 Paris Agreement are now unlikely, scientists say. The oil and gas industry is one of the largest methane emitters, through leaks throughout the natural gas production chain and companies venting gas from oil wells, storage tanks, and other production-related equipment.

Cutting Methane Has Powerful Short-Term Impact on Emissions

“If we want to do something [about global warming] that will have an impact on our kids and grandkids, reducing methane is probably the only thing we can do now,” said John Streur, chairman of Calvert Research & Management, which sponsored the study. Calvert is owned by Morgan Stanley MS.

Oil and gas firms are self-reporting their methane emissions, but evidence shows they may be severely underreporting them, according to the new study by two climate data and analytics providers, Geofinancial Analytics and Signal Climate Analytics, and sponsored by the Calvert Center for Responsible Investing.

Enter satellites.

The study analyzed data from direct satellite observation of 150,944 active wells operated by the top 25 listed U.S. producers, each observed an average of 53 times over the 12 months ended March 31, 2023.

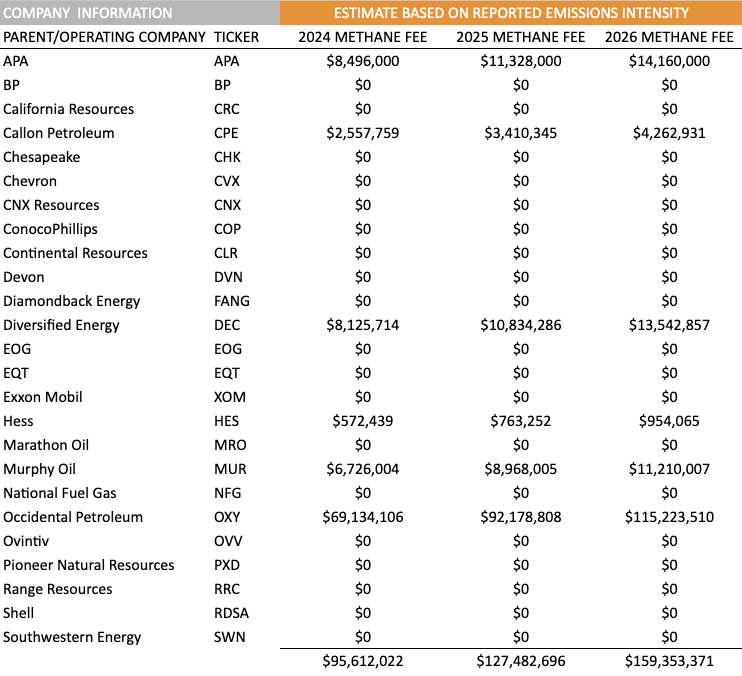

Existing emissions, the satellites observed, would result in roughly 12 times the amount of methane fees that people expect for the 25 largest U.S. producers. Based on self-disclosed emissions, the producers would have to pay methane fees of about $400 million to the U.S. government between 2024 and 2026, the authors estimate.

How Companies Self-Report Methane Emissions

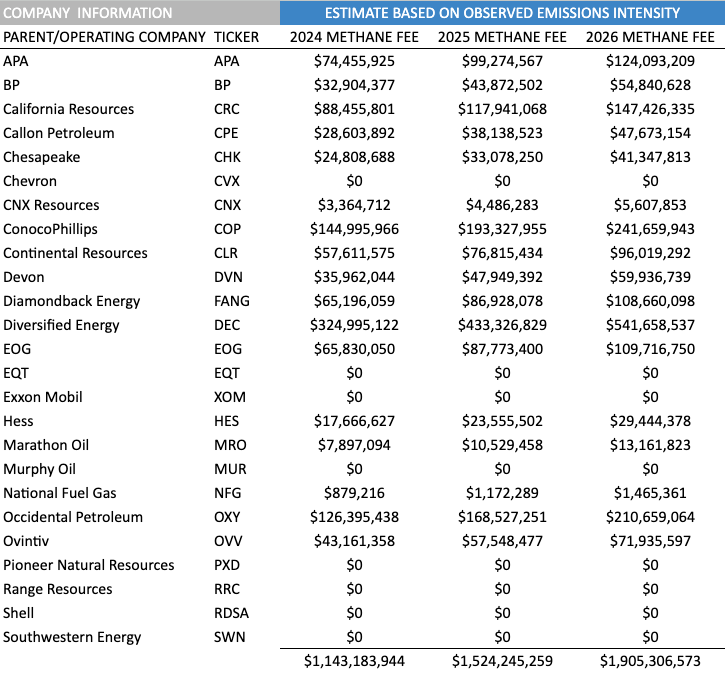

However, based on the satellite findings, the fees would be an estimated $4.8 billion—more than 10 times larger. The largest fees would be owed by Diversified Energy DECPF, ConocoPhillips, Occidental Petroleum, and California Resources CRC. Indeed, the gap between self-reported and satellite-observed emissions is large, especially for seven of the top 25 U.S. producers. The estimates assume no change in emissions level from those observed by satellite.

Methane Fees, Based on Satellite Data

“Highly reducing methane and other short-acting greenhouse gas emissions would result in a 13% reduction in temperature rise by 2100, versus the status quo scenario,” wrote Mark Kriss, CEO of Geofinancial, in an email.

“We see a significant opportunity to work with oil and gas companies, improve their methane tracking and reporting and work with them to urge them to reduce their emissions,” says Streur of Calvert. “There’s momentum within the oil and gas industry to address this.” According to the study, in addition to curbing global warming, reducing methane leaks would lower regulatory risk and fine exposure and help companies capture new markets requiring lower carbon intensity.

Low Costs to Cutting Methane Emissions

Oil and gas methane emissions represent one of the best near-term opportunities for climate action because the pathways for reducing them are well-known and cost-effective, according to the International Energy Agency. “Based on average natural gas prices seen from 2017 to 2021, around half of the options to reduce emissions from oil and gas operations worldwide could be implemented at no net cost; implementing these would cut oil and gas methane emissions by around 40%. Based on the record gas prices seen around the world in 2022, around 80% of the options to reduce emissions from oil and gas operations worldwide could be implemented at no net cost; implementing these would cut oil and gas methane emissions by more than 60%,” the agency writes.

Smaller producers are “identified with less effective methane management,” according to the Geofinancial and Signal Climate study. “Perhaps smaller firms not only lack the resources to manage methane emissions efficiently, but further … to accurately compute the facts on the ground, even compared to the underreporting across the sector in general.” The exception is Occidental.

“Dramatically reducing methane emissions and other short-acting gases between now and 2030 would flatten the greenhouse gas curve until 2050,” according to the study.

Correction: Owing to an error in Geofinancial Analytics’ database, an earlier version of this story displayed incorrect data and estimates for EQT’s methane exposure in two tables. The tables have been updated to reflect accurate data.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/d53e0e66-732b-4d50-b97a-d324cfa9d1f8.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PJQ2TFVCOFACVODYK7FJ2Q3J2U.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PVJSLSCNFRF7DGSEJSCWXZHDFQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/d53e0e66-732b-4d50-b97a-d324cfa9d1f8.jpg)