Can Dollar Stores Defy Retail's Woes?

Small tickets and low-income customers are safeguards.

Dollar and discount chains have been spared the pandemic’s ill effects on the retail sector, with their essentials-oriented store assortments, low prices, and proximity to customers propping up sales. Dollar Tree’s DLTR Family Dollar chain and Dollar General DG have shown strong to exceptional comparable sales growth through the first nine months of fiscal 2020. The two chains have outperformed namesake Dollar Tree stores, which carry more discretionary items, unlike the food, beverage, personal care, and household essentials-heavy assortments at Family Dollar and Dollar General.

Similar to their performance during the pandemic thus far, dollar and discount chains have defied the sluggishness endemic in much of brick-and-mortar retail over the decade leading up to the outbreak, opening new stores and delivering top-line growth in an environment that has stressed large swaths of the rest of the conventional channel. Dollar General and the Dollar Tree banner have consistently posted strong top-line growth, spurred by significant store footprint expansion. We ascribe the growth to the chains’ ability to address customer demand for convenience and the unique needs of lower-income shoppers.

The chains’ business models differ somewhat but nevertheless focus on delivering an array of branded and private-label items at low absolute dollar prices through a dense network of stores. Their value proposition is consistent with the retail zeitgeist, catering to time-starved customers’ rising demand for convenience. In PwC’s 2018 Future of Customer Experience survey, respondents indicated that efficiency and convenience were among the top four most important factors in the customer experience. Those surveyed also cited efficiency and convenience as the top two factors they would be willing to pay more to receive, ahead of characteristics like friendly service, easy payment, a loyalty program, or personalization.

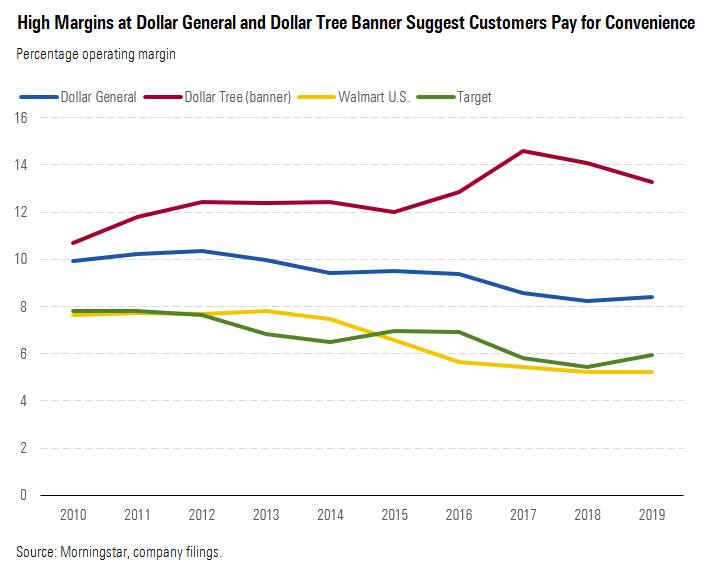

The survey data is borne out in Dollar General and Dollar Tree’s normalized operating margin performance, with high-single-digit and low-teens figures at the operating level, respectively, that are well in excess of larger general merchandise retailers such as Walmart WMT and Target TGT.

We believe the convenience trend will prove durable, with drivers such as faster-paced American lifestyles spurred by digitization and increasing demands on children’s time (requiring parents to shepherd them from activity to activity) re-emerging after the pandemic, joining ongoing pressure to meet rising education, housing, and healthcare costs.

We do not expect the pandemic to materially alter these long-term trends, particularly as the dollar and discount stores respond to the unique needs of lower-income households. Despite a fairly robust economy, we estimate that in 2019, approximately 30% of American households (or about 37 million) fell below the roughly $40,000 income threshold that Dollar General’s management cites as the upper bound of the cohort for which it believes it adds the most value. The proportion has held fairly steady; adjusted for inflation, the share was around 40% in 2008, even as the American economy emerged from the financial crisis and ensuing recession. However, the severity of the pandemic’s economic consequences could skew the share higher near term.

Lower-income households’ economic situation creates needs that are not necessarily met by large general merchandise sellers. For one, the need to minimize absolute dollar expenditures necessitates smaller pack sizes than cost-conscious customers generally prefer, as a lower-income shopper cannot necessarily afford to tie up scarce funds in building an inventory of items, even if a multipack offers a better per-unit value. As such, customers delay purchases to as close to the time of need as possible, increasing the premium put on convenience, as the timing of shopping trips for staple items becomes considerably less flexible. The trips themselves are a challenge, with inflexible, inconvenient, or costly transportation options (with shoppers facing either the hassle and difficulty in carrying large orders on public transit or the cost of fuel and vehicle operation for those driving) compounded by often minimal scheduling flexibility for individuals in hourly paid jobs.

Additionally, the stores balance their assortments between branded and unbranded products, with all items at low absolute dollar prices (even if in somewhat smaller formats). The chains’ extensive array of branded items is a benefit despite low-income customers’ limited funds. Particularly in categories in which consumption is conspicuous (such as beverages), social pressures can push shoppers to favor branded items. Furthermore, the branded assortment offers a trade-up option for flush shoppers who have just received a paycheck. Around 20%-30% of the assortment at Dollar General and Family Dollar (the two chains that cater most to lower-income households) is unbranded, while Dollar Tree’s more nonconsumable and discretionary lineup approximates 40%.

In our view, dollar and discount stores’ core customers are among the least likely to exhibit lasting change in their commuting habits as a result of the pandemic, suggesting that the convenience dynamic should hold. Entering the pandemic, lower-income shoppers had considerably fewer work-from-home options, and we do not believe the dynamic has changed materially. As blue-collar positions generally require physical labor, with an employee spending the workday at the jobsite, we expect such shoppers to continue to value the convenience that the chains’ dense store networks provide.

Unlike other segments of retail, the relationship between seller and customer can be a lasting one, as core dollar store shoppers have few trade-down options, while convenience can lead to continued sales even if the buyer’s state improves.

Although the channel’s ability to address the needs of lower-income families distinguishes it from more broadly oriented, mass-market general merchandise sellers (or higher-priced convenience stores), the chains’ convenience and value proposition can also draw customers from different income strata. Dollar General’s staples-heavy, value-oriented lineup generated around one fourth of its prepandemic sales from households with an income of $75,000 or more, a threshold around 20% higher than the national average. The chain’s income distribution had gradually been shifting higher before the outbreak, as households with incomes over $50,000 (more than its core customer’s up-to-$40,000 mark) constituted its fastest-growing customer cohort. The trend has likely accelerated during the pandemic, as customers with moderate incomes look to conserve funds. Although both banners’ core customers are in lower income brackets, we expect Dollar General to better cater to shoppers of more considerable means than Family Dollar, particularly in light of its 2019 partnership with FedEx, which has select rural Dollar General stores serving as package pickup and drop-off points. The arrangement should bring new shoppers initially drawn to a more convenient shipping location and subsequently exposed to Dollar General’s high-value branded lineup (particularly more impulse-friendly items whose appeal cuts across income strata). Additionally, Dollar General stores are often located in rural areas with few other sizable retail options (regardless of target income level) nearby, leading individuals in remote communities into the store for essentials regardless of their economic situation. We consider the isolated locations of many of Dollar General’s stores a significant source of competitive advantage.

The Dollar Tree banner is more broadly distributed, targeting middle-income suburban customers with a lineup that includes more discretionary items and is less suitable for the fill-in visits (between larger grocery shopping trips) that constitute Dollar General’s and Family Dollar’s primary target. This broadens the chain’s addressable market, but we believe it also exposes the Dollar Tree banner to more competition than Dollar General.

Online Growth Unlikely to Disrupt Sector Even before the pandemic, explosive e-commerce growth had reverberated through the brick-and-mortar retail landscape, leaving the likes of Payless, Sears, and Toys 'R' Us shuttered or near their demise. While we do not expect brick-and-mortar retail to vanish, we do believe virtually all growth in the broader sector will come from the digital sphere, despite such sales only constituting a low-double-digit percentage of overall prepandemic U.S. retail revenue. Digital shopping's growth has accelerated dramatically in the months since COVID-19 gained a foothold in the country, and while most store traffic should return after conditions normalize (likely in mid- to late 2021 as vaccines and improved treatments lead the pandemic to ebb), a portion of the shift is likely to endure as customers initially forced into the channel by stay-at-home orders embrace the convenience that e-commerce offers.

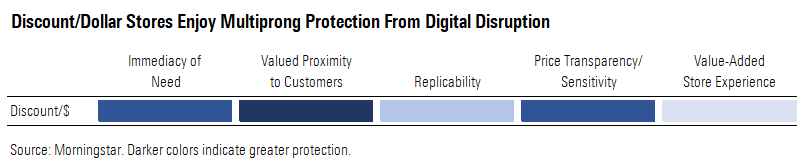

However, we do not believe all brick-and-mortar retailers share the same fate. In November 2019, we identified discount/dollar stores (along with home improvement chains, auto-parts sellers, and off-price apparel merchants) as likely to thrive despite the change roiling the broader sector. Our proprietary framework identifies five factors that can characterize digital-insulated retailers: ability to address immediate shopper needs, valued proximity to customers, a difficult-to-replicate business model, limited price transparency or consumer price sensitivity, and a value-added store experience. Discount/dollar stores scored particularly high on their proximity to customers and, for consumables-heavy chains like Dollar General and the Dollar Tree banner, their ability to meet immediate customer needs. Pricing dynamics also favor the sector.

Dollar General, Dollar Tree, and Family Dollar each have broad national networks of locations, averaging one store for every 20,200, 43,900, and 42,300 people, respectively, in the United States (as of the end of fiscal 2019). Around 75% of Americans live within 5 miles of a Dollar General store, and while Family Dollar is less dense (and has been culling stores as it rebanners certain locations to Dollar Tree and closes other underperforming units outright), its skew toward urban and suburban areas boosts its reach. While an online purchase may seem more convenient than even a visit to a nearby store, lower-income shoppers face particular challenges, such as inflexible work schedules with long hours and inconvenient package receipt if the parcel can’t be left at the door.

From the standpoint of meeting immediate shopper needs, the chains cater to lower-income households that must minimize absolute dollar spending. Since such households cannot invest in large package sizes and often must make purchases close to when a need arises, the cohort has a relatively high immediacy of need for the household and personal care and food staples that the chains stock. Small pack sizes and modest incomes also lead to low average normalized tickets, and our research indicates shipping costs (charged by the dollar/discount stores or other leading omnichannel or brick-and-mortar sellers) can range from 40% to 75% of the average purchase. With customer dollars scarce and normalized retail operating margins thin (low to mid-single digits for branded food items, by our estimate), we see little room for lower-income shoppers or sellers to take on shipping costs, particularly as the customer set is generally well outside of Amazon Prime’s AMZN wealthier main demographic. Although Walmart’s recently introduced subscription service more directly targets dollar and discount stores’ core customers, its $35 order minimum for free grocery delivery (which can be 3-4 times the sector’s average ticket size) is likely to keep those smaller-box alternative chains high on target shoppers’ lists for the fill-in trips that constitute the bulk of their sales. Combined, we believe these factors should keep the channel relatively well protected from digital disruption.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/05-09-2024/t_fab10267147f40fb93a1deb8a0b6553b_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/E3DSJ6NJLFA5DOKMPQRAH5STMU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)