Retirement: The Other Economic Gender Gap

Women lag behind men in building retirement assets. But the gap is starting to narrow, reports contributor Mark Miller.

The gender pay gap is a hot topic these days, but it's not the only economic gender gap. Women also are lagging behind men in building retirement security.

Lower pay translates into a gap for women in retirement security, reducing Social Security benefits, pensions, and retirement saving. At the same time, women enjoy greater longevity, which means resources often must be stretched over a longer retirement.

"Americans generally are facing a crunch when it comes to retirement--it will impact men and women," says Mark Browne, head of North America Channel and global institutional and retirement marketing at BNY Mellon Investment Management. "But for women, there is a compounding effect."

There are some hopeful signs that the gender gap in retirement security could shrink in the years ahead. Women are working longer, and their participation rate in workplace retirement plans is rising. And more women are boosting their Social Security income by delaying their claim of benefits.

Retirement Headwinds Many women will need to stretch their savings over a longer retirement than men. The average 65-year-old woman is expected to live to 88.8, compared with 86.6 for men, according to the latest mortality tables from Society of Actuaries. Compared with the tables from 2000, the figures are two years higher for men, and 2.4 years higher for women.

Meanwhile, income inequality remains a huge structural economic problem. A woman who works full time over a 40-year period loses $435,480 in lifetime income (today's dollars) due to the gender gap in pay, according to the National Women's Law Center, a nonprofit legal and advocacy group. Put another way, the typical woman needs to work 11 years longer than the typical man to achieve accumulated income parity.

Some--but not all--of the gap can be chalked up to one word: caregiving. Women tend to take time out of the workforce to care for children, parents, and spouses. Those career interruptions have real economic consequences. A MetLife study estimated the total lifetime impact for the typical worker at $324,000--a figure that includes lost Social Security and pension benefits.

The average Social Security benefit in 2014 for women older than 65 was $14,234 a year, compared with $18,113 for men, according to Social Security Administration data. A study on women and retirement security (based on U.S. Census data) by the National Institute on Retirement Security found that men receiving defined benefit pensions received $17,856 in median income in 2010, compared with $12,000 for women.

The NIRS found that women are 80% more likely than men to be impoverished after age 65, and women age 75 to 79 are three times more likely than men to live in poverty.

Signs of Progress Despite these disturbing statistics, there are signs that things are getting better. According to the NIRS study:

- Women are working longer. Labor force participation among women ages 55 to 64 hit 61% in 2010, up from 53% in 2000. That should be a plus over time, as women build greater Social Security credits, savings, and pension benefits.

- The retirement plan coverage gap has narrowed. Forty-six percent of women participated in a workplace retirement plan in 2012--the same rate as men. As recently as 1998, there was a five percentage point gap, with just 41% of women participating. And Vanguard reports significantly higher deferral rates for women than men among participants in workplace plans that it administers.

- Social Security claiming ages are rising. The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College has reported that average retirement ages (for men and women) have risen about two years over the past 25 years. And in 2010, 11% more women were waiting to claim Social Security at their full retirement age than in 1985; 9% were claiming at age 70 or higher. That's good news, especially for middle- and lower-income women: In households with incomes less than $80,000, older women depend on Social Security benefits for a majority of their income, the NIRS reported.

"Women are doing everything people are telling them to do," says Diane Oakley, executive director of the NIRS. "They are staying in the workforce longer, and working for employers who offer retirement plans at greater rates."

The data on accumulation of savings offers a mixed picture of progress.

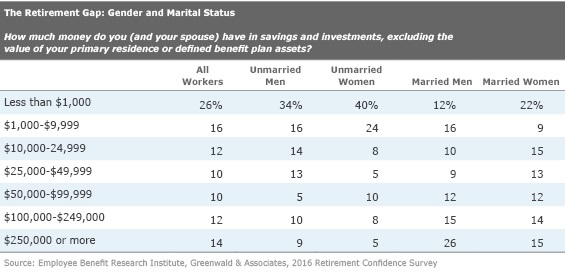

Unmarried men are more likely than unmarried women to report having saved for retirement, and 44% of unmarried women have less than $1,000 saved, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute (see chart).

But Vanguard reports that women with incomes below $100,000 actually are saving more than men--despite their lower incomes. For instance, women earning $30,000 to $50,000 have average account balances that are 18% higher than their male counterparts, and median balances that are 50% higher.

Policy Changes Eliminating the gender pay gap would be a game changer in improving retirement prospects of women. The Obama administration and Congressional Democrats have tried to push federal law and policies in this direction, but policymakers also should consider a range of sensible Social Security reforms that would address the gender gap. These include beefing up Social Security survivor benefits, providing benefit credits for caregivers, and providing a bump in benefits beyond age 85.

Requiring employers to open up workplace retirement saving plans to part-time workers also could help. Another good idea: improve the Saver's Credit, which is a nonrefundable tax credit up to $1,000 for low-income workers ($2,000 for couples) who contribute to workplace plans or IRAs. Many policy experts would like to see the credit made refundable--currently it is not available to workers who do not have a federal income tax liability.

Reforms in the long-term care insurance market are long overdue and would benefit women disproportionately--they often play the role of primary caregiver themselves and outlive spouses. Policy ideas are emerging that would make private long-term care policies easier to purchase and, perhaps, less expensive.

Steps Women Can Take Women who don't want to hold their breath waiting for the policymakers to improve things can take meaningful steps on their own to close the gap.

Optimizing Social Security tops the list, and most married couples will benefit by doing joint planning that assumes a longer-lived female spouse. A wide array of spousal and survivor strategies can be leveraged, usually involving delayed filing by the higher-earning spouse.

It's tough to beat the return on a delayed filing credit; it translates into roughly 8% higher monthly benefits for each year of delay from age 62 to 70--risk-free. Once you do file, cost-of-living adjustments are awarded annually, and you will receive a COLA for the years that you delay.

Single women should also consider strategies for delayed Social Security filing--either by working longer, or funding the early years of retirement from saving.

In all cases, it pays to run the numbers. Help is available from a variety of sources.

Save more if you can, of course. If that's difficult due to competing demands on your income, keep in mind that you may be able to play catch-up in the years just before retirement. Contribution limits for tax-deferred retirement accounts are higher after age 50, and it's entirely possible to make headway.

Rising Value of Advice Women can also consider hiring a fiduciary fee-only planner with whom you are comfortable and can trust. Studies show that women don't trust advisors, or don't feel that they are speaking their language.

A telling statistic: Pershing LLC research found that 70% of women fire their advisors within one year of a spouse's death. A study by the Center for Talent Innovation, focused on opportunities for advisors to serve female clients, found that 67% of women feel their advisor does not understand them--or is not interested in them. This trend holds true across all subsegments of the female market, irrespective of age and asset levels.

"Either women are unhappy with the financial advice they are getting, or simply don't trust the person," says Browne.

This is where the new fiduciary regime for retirement advice will help. The "best interest" standard that will apply to all retirement account advice should make it easier for clients--women and men--to feel confident about the advice they are receiving.

Do women need planning help more than men? Not from a financial literacy standpoint. The CTI study found no meaningful gender gap in financial literacy--but women are 44% less likely than men to consider themselves "knowledgeable" about investment and finance. That, in turn, leads to excessively risk-averse investing habits that needlessly hamper long-term returns.

By the way, all those "confident" men also are more likely trade themselves into lower returns. One research paper found that men are 45% more likely to trade stocks than women--and that their trading reduced net returns by 2.65 percentage points annually, compared with 1.72 percentage points for women.

How's that for a gender gap?

Mark Miller will be speaking about women and investing at the upcoming Morningstar Investment Conference. To view the complete conference agenda, click here.

Mark Miller is a retirement columnist and author of The Hard Times Guide to Retirement Security: Practical Strategies for Money, Work, and Living. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)