Demographics Will Weigh Heavily on China Over Next Decade

Changes to fertility, age composition, and urbanization will influence China’s economy in the decade to come.

This article is the first in a four-part series on China’s next 10 years. Subsequent articles will discuss growth and productivity, rebalancing, and debt.

The influence of demography is often imperceptible quarter to quarter or year to year. But over the long term, it can prove decisive. For much of China’s past 30 years, demography aided extraordinary growth and supported an increasingly investment-heavy economic model. In the next 10 years, we expect demographic change will drag on growth rather than drive it and radically reshape China’s economy. The seemingly limitless supply of “surplus” rural labor, which fueled rapid urbanization and productivity gains, will begin to dry up. The working-age population will contract just as the senior population surges. China’s unusually high support ratio--the number of working-age adults for each child and senior--will collapse, draining the huge pool of savings that funds outsize investment outlays but stabilizing consumption growth as the overall economy slows. Below, we detail how changes to fertility, age composition, and urbanization will influence China’s economy in the decade to come.

Fertility: Looser Family Planning Laws Will Not Avert an Eventual Plunge in Births If demography is destiny, the future begins with fertility. Many of the demographic changes China will experience over the next 10 years--slowing population growth, a shrinking labor force, and a rising support ratio--are consequences of a premature fertility crash caused by harsh family planning laws.

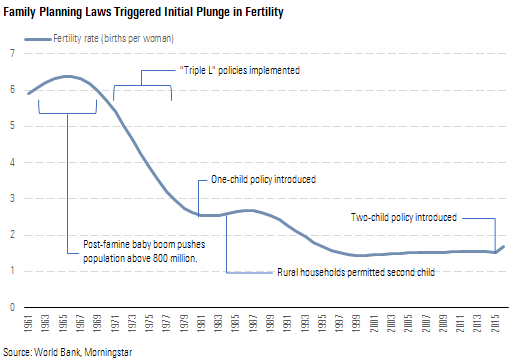

The Chinese government has a long history of meddling in reproductive decisions. Initial efforts to manage population growth began in the early 1950s, shortly after China’s population eclipsed the 500 million mark, but had little effect. A renewed push to curb births came in 1970 with the introduction of policies that prescribed late marriage, long birth intervals, and small families. From 1970 to 1980, China’s total fertility rate (the number of births a woman might expect to have in her lifetime) plunged from 5.7 to 2.6, an unprecedented drop for a what was still a poor and largely agrarian country. The one-child policy, implemented in 1980, had comparatively less impact on fertility, which fluctuated between 2.5 and 2.6 births per woman in the following decade. Then, from 1990 to 2000, despite no major further tightening of family planning laws, fertility fell again, slipping to 1.45 in 2000. Fertility fluctuated between 1.5 and 1.6 for most of the 2000s, well below the replacement level of 2.1 births.

Persistently low fertility prompted concerns that China would grow old before it grew rich. In the past few years, the government began to loosen restrictions. Beginning in 2016, the two-child policy went into effect, contributing to an 8% increase in births (from 16.6 million to 17.9 million) and boosting fertility to 1.7. Relaxed family planning laws have prompted some to speculate that China’s fertility rate will continue to rise.

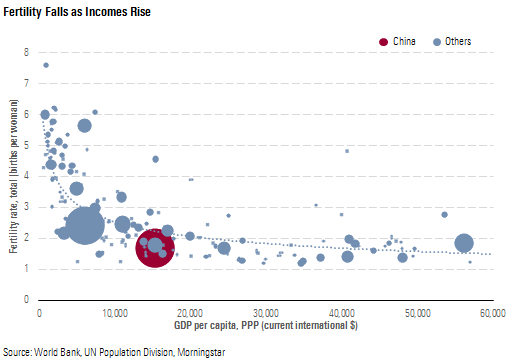

We’re more circumspect. Surveys of Chinese couples’ childbearing intentions suggest economic considerations, not legal restrictions, largely explain China’s low fertility rate today. China would not be unusual in this regard. Rising incomes are associated with falling fertility globally. This is a consequence of a variety of factors. For example, female workforce participation and college education facilitate income growth but also tend to depress fertility by delaying marriage and births. Urbanization and industrialization are also linked with income growth and falling birth rates. For agricultural households, larger families can be advantageous, since children can be put to work on the family’s plot. For urban households where education is a prerequisite to success, larger families can be a disadvantage as they have less to invest in each child. For China, decades of high-income growth and urbanization have changed the economic logic of family size.

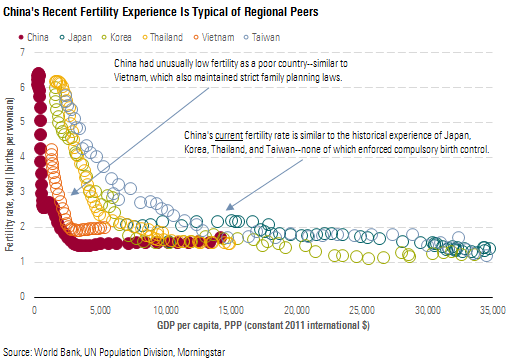

While Chinese fertility (1.7) is somewhat low for a middle-income country (2.2 is the norm), it’s typical of neighboring countries’ historical experience. Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand, none of which enforced compulsory birth control, had similarly low fertility rates at comparable points in their economic development.

Had the government liberalized family planning laws in the 1980s or 1990s, it might have been reasonable to expect a sustained fertility increase. That seems unlikely today. Although we expect 2016’s fertility gains will be largely maintained in 2017 as pent-up demand for a second child is released, those gains are likely to prove temporary.

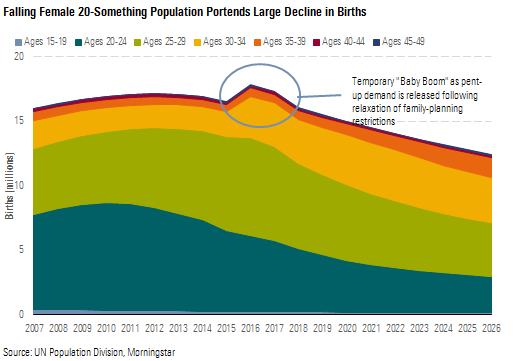

While we don’t forecast a significant drop in China’s fertility rate, a major decline in births is nonetheless likely. That’s because the population of childbearing-age women is set to fall over the next 10 years, with losses concentrated among 20-something women. By 2026, China’s population of 20- to 29-year-old women will fall by more than one third. That’s significant because the birth rate among 20- to 29-year-olds is roughly 5 times that of 30- to 39-year-olds and 50 times that of 40- to 49-year-olds.

Applying our forecast for age-specific fertility to the projected population of childbearing-age women, we estimate 20 million fewer babies will be born over the next 10 years than in the past 10 years (145 million versus 165 million), a decline of 12%. We forecast births will have fallen to 12.4 million by 2026, down 30% from the 17.9 million births in 2016.

Age: Graying Population Will Unwind Many Long-Standing Economic Trends Decades of falling fertility set in motion a long-term demographic transformation that will continue to unfold in the next 10 years. Population growth, already slowing, will nearly grind to a halt by 2026 amid falling births and a steady rise in mortality. The age composition of China's population will change dramatically over the next 10 years.

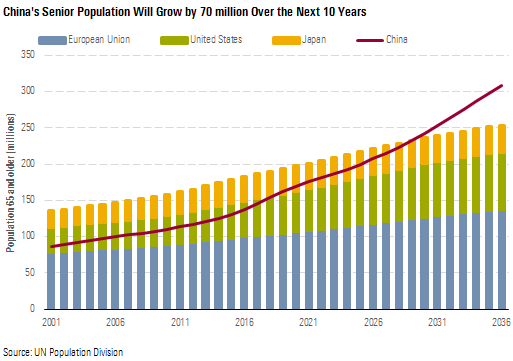

Seniors will be by far the fastest-growing age group. By 2026, China will have 207 million people who are 65 or older, up 50% from 138 million in 2016. A few years after that, China will have more seniors than the United States, the European Union, and Japan combined. And by 2036, there will be nearly as many Chinese 65 and older than there will be Americans of any age.

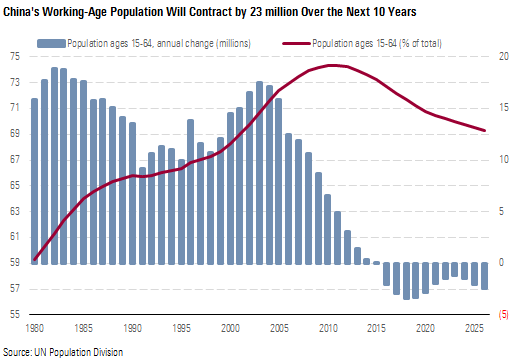

China’s working-age population, those aged 15-64, will contract by over 20 million over the next 10 years. While not an especially large drop for a country of China’s size, this will mark a significant trend reversal. Since 1980, China’s working-age population has expanded by more than 400 million (from 582 million to over 1 billion).

A shrinking workforce will have a modest negative impact on GDP growth. We estimate reductions to China’s labor supply will subtract, on average, about 0.1% from GDP annually over the next 10 years. By comparison, labor supply growth added about 0.4% annually to GDP in the 1990s and 2000s. However, increased human capital per worker should at least partially offset the falling number of workers. The population entering the workforce will be far better educated than the population that will retire.

While labor supply contraction is unlikely to dramatically alter the trajectory of China’s GDP growth, it will have profound implications for the country’s GDP mix. To begin with, China’s shrinking working-age population portends upward pressure on wages. Although we do not expect wage growth to accelerate in the next 10 years, we do expect it will continue to outstrip GDP growth. As a result, the household income share of GDP, which had been falling for most of the 2000s, is likely to climb in the next 10 years.

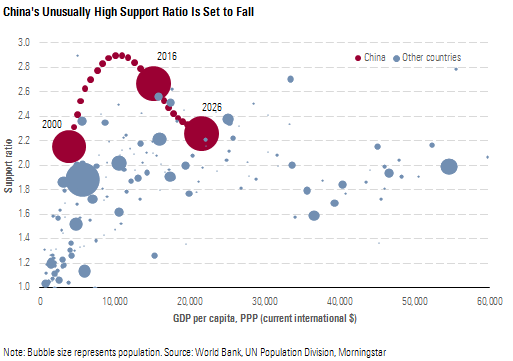

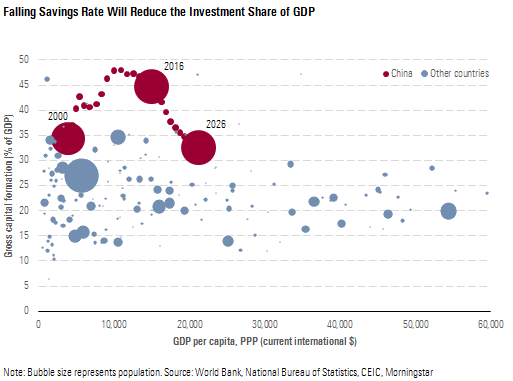

China’s extremely high household saving rate is likely to fall as the population ages. A big reason China’s households save a lot is because, compared with the typical country, China has a lot more working-age adults (net savers) than it does children and seniors (net spenders). This demographic support ratio will fall considerably over the next 10 years. Just as China’s household saving rate increased in near lockstep with a rising support ratio over the past couple of decades, it is likely to decline as the support ratio falls.

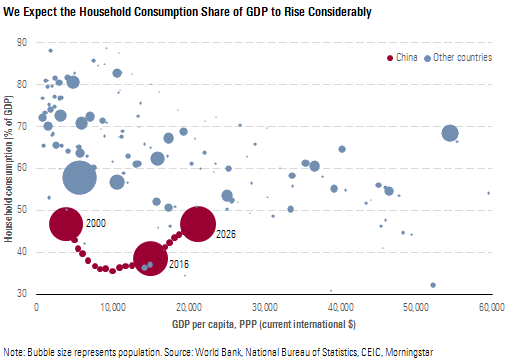

A falling household saving rate combined with a rising household income share of GDP should support robust household consumption growth in the next 10 years, even as the economy slows. While the household consumption share of GDP has climbed in recent years, from a trough of 36% in 2010 to 38% in 2016, Chinese households still consume far less of their country’s output than counterparts globally. We expect that gap to close considerably by 2026.

A falling household saving rate will drain the pool of funds available for investment spending. Households contribute roughly half of national savings and serve as a major net lender to China’s heavily indebted corporate sector. To a considerable extent, the duration and magnitude of China’s investment boom has been made possible by rapid demographic transformation. Absent a high and rising support ratio, it’s inconceivable that China’s saving rate would have been high enough to sustain the country’s increasingly profligate level of investment. As the support ratio falls, once-plentiful domestic funding will dry up, and China’s extremely high investment share of GDP will come back to earth.

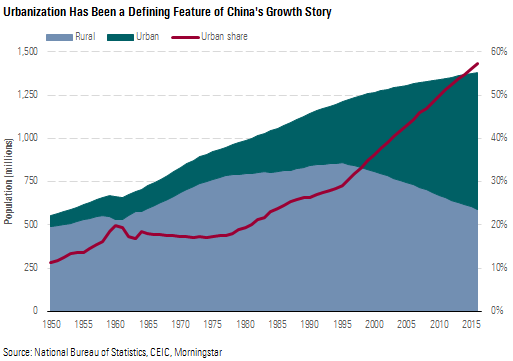

Urbanization: While Far From Over, Farm-to-Factory Migration Will Slow Considerably Urbanization and economic growth have been linked since the founding of the People's Republic in 1949. For the first 30 years under Communist Party rule, China saw little of either. In 1960, 20% of China's population lived in cities; two decades later, in 1980, 19% did. Then as central planning and stagnation gave way to reform and growth, China urbanized at a spectacular pace. According to official figures, the country's urban population expanded from 191 million in 1980 to 793 million in 2016, boosting the urbanization rate to 57%.

The narrative arc of reform-era China suggests a strong connection between urbanization and economic growth. But the extent to which urbanization has caused economic growth, or vice versa, is far from obvious. Correlation does not establish causation.

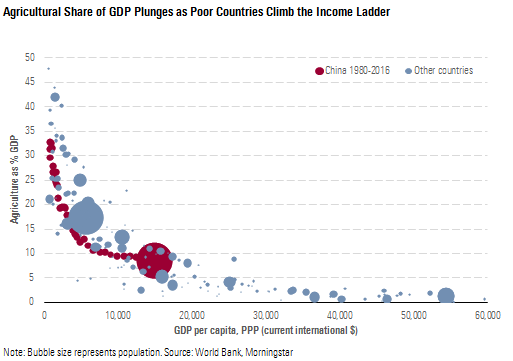

Rather, urbanization and economic growth can both be thought of as byproducts of labor migration from the largely rural agricultural sector to the largely urban industrial and service sectors. Moving workers from farms to factories and storefronts boosts productivity, expands economic output, and urbanizes the population. Spatial (from rural to urban) and sectoral (from agriculture to industry and services) labor reallocations go hand in hand.

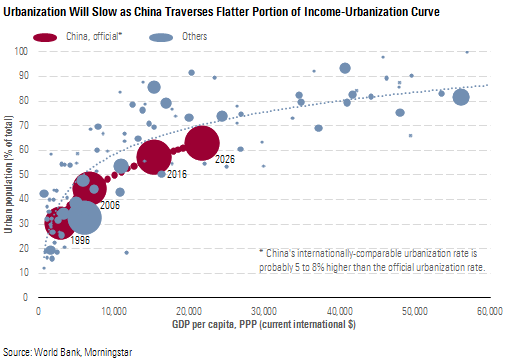

This process tends to lose steam as a country climbs the income ladder. Low-income countries, with enormous agricultural workforces, can reap enormous productivity gains by transferring labor from farms to cities. Middle-income countries, with smaller slices of their workforce engaged in farming, cannot. Consequently, labor migration and urbanization both tend to slow as incomes rise.

China appears close to exhausting the seemingly limitless pool of “surplus” rural labor that fueled rapid urbanization and productivity gains in the reform era. The Chinese economy is far less dependent on agriculture than it was when the urbanization process kicked off in earnest. As of 2016, agriculture accounted for less than 9% of China’s GDP, fairly typical of a middle-income country. Following massive migration from rural to urban areas over the past several decades, a much smaller share of China’s workforce is engaged in farming—probably about 20% based on academic studies that adjust for the overcounting of agricultural employment in official statistics.

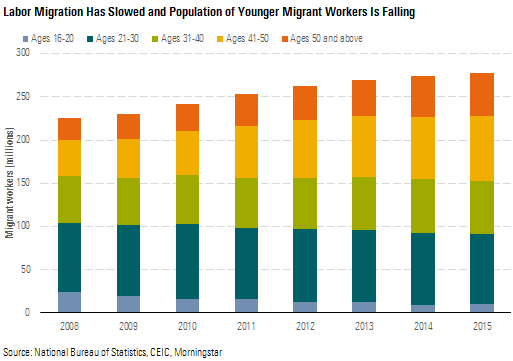

Data on migrant labor also suggest China’s rural labor surplus is drying up. Labor migration has slowed meaningfully in recent years to 4.2 million in 2016 from an average of 10.9 million in 2010-12. The aging of the migrant workforce points to a similar conclusion. The population of migrant workers under 30 years old has been declining since 2008, slipping from 104 million to 92 million. In this case, the data would seem to support anecdotal evidence of a barbell age distribution in China’s rural villages: children and older adults with no younger adults in between.

The tendency for urbanization to decelerate among middle-income countries like China is also evident in the global relationship between income and urbanization. The link between urbanization and income is not linear. A country that doubles its GDP per capita from $2,500 to $5,000 is likely to see a 31% increase in its urban population. Doubling incomes again to $10,000 is accompanied by 24% growth in the urban population. The next doubling generates a 19% increase in urbanites and the next, a 16% increase. Over the past 30 years, China traversed the steeper portion of the income-urbanization curve as it moved from low-income to middle-income status. Going forward, the country will move along the flatter portion.

Although the process of moving farmers to factory floors and storefronts is far from over, it is likely to slow over the next 10 years. Accordingly, we expect China will continue to urbanize, but at a decelerating pace. We project urban population growth of about 100 million over the next 10 years, a huge figure, but considerably less than the 209 million expansion of the past 10 years.

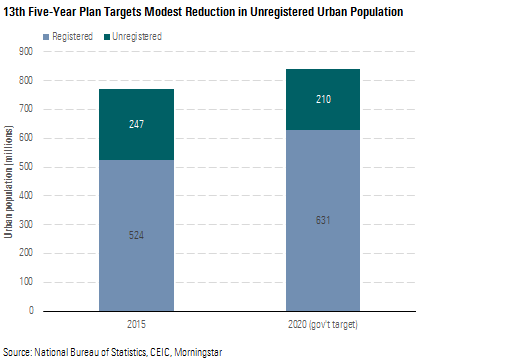

While fewer migrants will move to cities, the quality of life for those who do is likely to improve. Reforms of the household registration, or hukou, system will see more of China’s estimated 245 million unregistered migrants gain access to publicly funded healthcare, education, and pensions and increasingly spend like full-fledged urbanites.

But hukou reform is likely to be slow and uneven. Extending full and immediate rights to all migrant workers and their families would be unpopular with many registered urban residents. Public schools and hospitals would be unprepared to accommodate a massive increase in system usage. Local governments balk at the cost, estimated at between 1.2% and 4.5% of GDP per year. There are also fears that full liberalization might trigger a flood of migration to urban areas, disrupting social stability while exacerbating any service capacity and cost problems.

Sustainable Growth Will Require Reform The government's gradual and often halting approach to hukou reform reflects the conflicting goals that have hindered the broader reform program. On one hand, policy-makers clearly understand the prospective benefits of reform, especially as it concerns China's long-term term development. The 13th Five-Year Plan, covering 2016-20, attests to at least a theoretical commitment to aggressive reform on a wide variety of subjects.

But reforms by their nature involve risk: to economic growth, social stability, and state control. The disappointing (and sometimes backward) pace of reform under the current leadership reflects an acute sensitivity to those risks. Premier Li Keqiang expressed the dominant mindset in his March 2017 speech to the National People’s Congress, asserting “stability is of overriding importance.”

But as we’ll argue in a forthcoming article on the 10-year outlook for growth and productivity, short-term stability comes at a steep cost to China’s long-term growth trajectory by exacerbating many of the country’s underlying problems. Reforms must accelerate if China is to boost flagging productivity and climb the income ladder. If it does not, the middle-income trap looms.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ecf6f262-5697-406a-a91d-cd20ff52a617.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2a921230-1c64-42c5-8f93-672d46002cce.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GJMQNPFPOFHUHHT3UABTAMBTZM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZYJVMA34ANHZZDT5KOPPUVFLPE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ecf6f262-5697-406a-a91d-cd20ff52a617.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2a921230-1c64-42c5-8f93-672d46002cce.jpg)