Where Do Bank-Loan Funds Go From Here?

The bank-loan Morningstar Category has experienced volatile trends in flows over the past few years.

A version of this article was published in the August 2016 issue of Morningstar FundInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of FundInvestor here.

These are interesting times for bank-loan portfolio managers. Bank-loan funds have proved to be especially prone to whipsawing views about the path of interest rates. Like high-yield bonds, bank loans, also referred to as floating-rate loans, are usually issued by below-investment-grade companies, so credit risk is still high, and returns typically display a higher correlation to equities than traditionally safe-haven bonds like Treasuries. If the economy is weak or in recession, this asset class may not perform well. For example, the bank-loan Morningstar Category fell 29.8% in 2008 (it also surged by 41.8% in 2009).

However, bank loans are higher in the capital structure compared with traditional corporate bonds and are also secured by assets of the issuing firm, whereas bonds are typically unsecured. In other words, in the event of bankruptcy, bank loans come first, thus making them safer bets with regard to credit risk. This means that bank loans should hold up relatively well compared with high-yield corporate bonds in the case of a default or general economic weakness, even though they may still experience losses.

There's a strong case that bank loans can help insulate investors from the price declines that traditional bonds would experience when rates rise. The interest paid by bank loans is determined in part by Libor rates (typically between 30-90 day Libor, depending on the individual loan), and the floating-rate nature of these loans means that income payments should actually increase when that key interest rate rises. There is a catch, though: Libor floors. Most bank loans issued post-financial crisis include a floor, around 1% on average across all outstanding bank-loan issues, that Libor rates must surpass before income payments adjust upward.

Despite these seemingly attractive qualities, investors have fled the category en masse over the past two years. Bank loans gained attention in 2013 when former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke suggested rates could increase following the end of the Fed's quantitative-easing program. Following this "taper tantrum," assets under management in the bank-loan category doubled from $75 billion at the start of 2013 to almost $150 billion by March 2014. Since then, investor sentiment toward the category has reversed, and persistent outflows caused categorywide assets to plunge back to just $89 billion at the end of June 2016.

Weakening fundamentals, especially in the energy and commodity sectors, likely drove some of these outflows. However, a shift in interest-rate expectations may have played a larger role in driving outflows. Longer-term rates, like 10- and 30-year Treasury yields, have surprisingly declined despite Bernanke's 2013 proclamation. And while Libor rates have increased lately because of reforms in money market fund regulation (the three-month Libor stood at 0.80% as of Aug. 19, 2016, for instance), this important interest rate still remains well below many bank loans' 1% Libor floors, so income payments have yet to adjust upward.

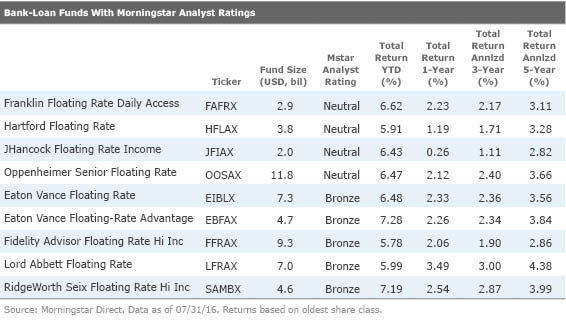

The Federal Reserve has regularly indicated a desire to increase rates but has yet to follow through because of uncertainty in the global economy, which has worked against bank-loan funds. Liquidity is also particularly troubling for bank loans, because of archaic trading traditions that cause settlement times (the time between when a manager sells a loan and actually receives cash for it) to increase to as long as 14 days, if not longer. This liquidity dynamic is the primary reason Morningstar's bank-loan category does not have any funds with a Morningstar Analyst Rating higher than Bronze.

In the current economic environment, where growth is stable but not strong enough for the Fed to raise rates, it's possible that high-yield bonds may continue to outperform bank loans. Over the trailing five-year period ended July 31, 2016, the bank-loan category returned an annualized 3.5%, while the high-yield bond category returned 4.9%. However, if the economy is strong enough that the Fed does raise rates, or if Libor rates surpass the 1% Libor floor present in most loans' terms, bank loans may provide some downside protection relative to other, more interest-rate-sensitive fixed-income sectors.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5WSHPTEQ6BADZPVPXVVDYIKL5M.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BNHBFLSEHBBGBEEQAWGAG6FHLQ.png)