The Problem for Active Management Isn't Indexing

Instead, it is that there are too many active managers.

Across the Board Vanguard recently published a short paper called "MYTH: Active management performs better in certain market segments." Taken literally, that claim is untrue. Over any time period, some categories of active funds fare better than others. Thus, per Morningstar's Active/Passive Barometer research, three times as many actively run emerging-markets stock funds beat their benchmarks over the trailing 10 years as did active large-blend U.S. stock funds.

The title isn’t fully accurate at the next level of abstraction, either. Not only do some categories of active funds outperform others over a single time period but extending those studies also uncovers some persistence. Active emerging-markets funds routinely give indexers a stronger fight than do large-blend U.S. stock funds. Small-company stock funds have more relative winners than do blue-chip funds.

But I accept the thesis at its highest level: No matter what the investments, or where their location, active managers face similar issues. They must overcome their cost disadvantage by outsmarting other market participants. However, today’s participants are better prepared than ever before, which means that active managers can no longer succeed by being very good, or even excellent. To succeed, they must be outstanding.

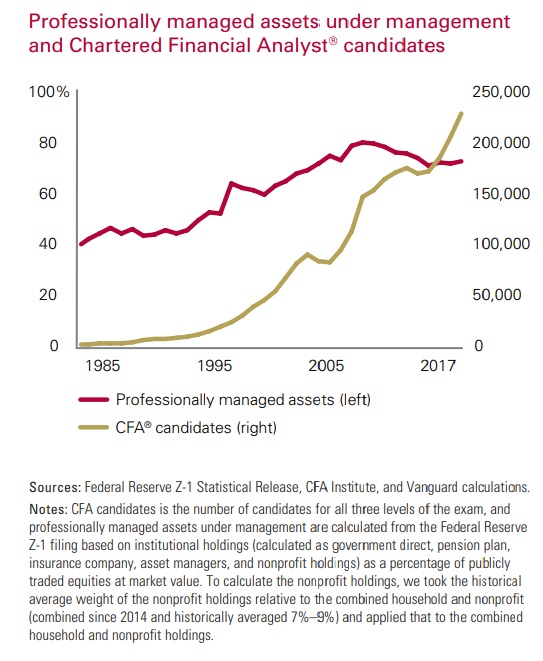

Getting Crowded The Vanguard paper graphically supports that point. Ignore the red line on the diagram below; we'll address that subject shortly. The gold is what matters. It represents the number of candidates registered for the Chartered Financial Analyst exams. To be sure, earning the CFA designation is but one way to attain investment training; it is not as if the industry was bereft of professionals before 1985. But without question, the field has become more crowded.

Source: Vanguard

The CFA effect has been wide-ranging. When the program started, it only taught equity analysis exclusively to Americans. That raised the level of investment competition for U.S. stock funds but left other investment categories untouched. Over time, though, the CFA Institute expanded the curriculum to cover bonds of all flavors, alternative investments, and asset allocation. It also went international. This year, 75% of CFA candidates live outside the United States. Wherever the financial market, it has plenty of local experts.

The question then becomes, what are all these trained investors doing, when indexing has become so popular? After all, index funds require few CFAs. They demand careful operational attention and a portfolio manager to oversee the results, but they need no research staff. The chart’s gold line seems to have headed in the wrong direction. As indexing has grown, the number of investment professionals should be shrinking.

Active Abounds Well, here's the thing: Indexing is not as prevalent as is commonly believed. Last week, my co-workers circulated a 2017 report from BlackRock that I had missed, "Index Investing Supports Vibrant Capital Markets." (Now there's a dull title.) Rather than look only at public U.S. funds, which is typically how active management versus indexing studies are conducted, BlackRock measured how all investment assets are deployed. And those numbers are ... remarkable.

Returning to Vanguard's chart, the red line shows that since the early '80s, the percentage of U.S. assets managed professionally has risen to almost 80% from 40%. The pattern is similar outside the United States. One might think that development is linked to the boom indexing. But that is not so. On the contrary, BlackRock's paper demonstrates that most of the red line's movement owes to growth in active management.

Within U.S. equities, BlackRock reports that 12.4% of the stock market’s capitalization is held by index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. (Those figures are from December 2016; they are somewhat higher today.) Another 16.8% is possessed by active funds, which means that publicly registered funds hold just over 28% of the U.S. stock market. The remaining 72% operates largely in the dark, as there is only limited information about how those assets are invested. Pretty clearly, though, much if not most of those monies are actively run.

Active management is more prominent yet when viewed from the global perspective. Doing so required BlackRock to make a host of assumptions; therefore, its estimate may be off by a few percentage points. But even so, the conclusion is unmistakable. BlackRock finds that less than 17.5% of the world’s equities are indexed, either directly through funds or indirectly as part of an institution’s investment strategy. The vast majority is managed actively.

What’s more, those active assets affect the stock market's pricing much more than do the indexed assets. Not only do the indexers take the quotes that the markets give them, rather than sway prices by buying those securities that the active manager finds appealing and selling those that she does not, but they are also much less likely to trade. Annual turnover for actively run U.S. equity accounts is 80%, writes BlackRock, as opposed to 7% for the indexing average.

Look Within Indexing, justifiably, dominates the headlines. For many years now, index funds have dominated the sales charts, with their actively managed rivals in net redemptions--a pattern that shows no sign of slowing. But indexing is not yet large enough to distort the financial markets. The challenge for active managers is not from the outside. It comes from within. It comes from the many tens of thousands of investment professionals who have raised the level of skill required to succeed at active management--and from the tens of thousands of new entrants who join the industry each year.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)