The Case for Vanguard

The firm still embodies founder Jack Bogle’s spirit.

New Vanguard doesn’t look much like old Vanguard. Whether it’s selling advice, launching high-conviction active funds only for advisory clients, or offering private equity, it is different.

What's also different is that many longtime observers have now begun to question the company. Morningstar's John Rekenthaler proposed that Vanguard has lost its way, while the Wall Street Journal's Jason Zweig charged it in at least one instance with failing the small investors whom Vanguard founder Jack Bogle championed. One financial advisor has even suggested that Bogle would roll over in his grave if he knew what was happening.

While critics have drawn attention to issues that would have irked Bogle and problems that he himself had trouble taming, such as customer service missteps, Vanguard still reflects his image more than tarnishes it. Indeed, it’s still a mission-driven company whose competitive zeal redounds to investors’ benefit, and that commends a positive outlook for Vanguard.

Negative sentiments rest on two pillars: industry rivalries’ corrosive influence and present-day Vanguard falling short of its former self. Despite some merit, both pillars struggle to bear the weight placed upon them.

Critics Are Wrong About Corrosive Competition

Owned by its U.S. funds and indirectly their shareholders, Vanguard has provided them with strong investment options for fees that keep dropping as the firm grows. Rivals who once scorned Vanguard’s pioneering indexing efforts now offer their own passive strategies, and the biggest have sought to match if not undercut Vanguard on fees for broad market exposure and single solutions like target-date funds.

True, these price wars recently led to some collateral damage. When Vanguard lowered the investment minimum for an institutional version of its target retirement series, money flooded in from a more-expensive retail sibling, triggering big 2021 capital gains distributions for the remaining taxable investors. Vanguard should have anticipated this problem and either avoided it or warned investors about it.

But Vanguard has also saved its investors lots of money in taxes through eliminating index funds' capital gains (using the exchange-traded fund share class and in-kind redemptions). And overall, lower costs have been great for investors, while the competition hasn't cost Vanguard its integrity.

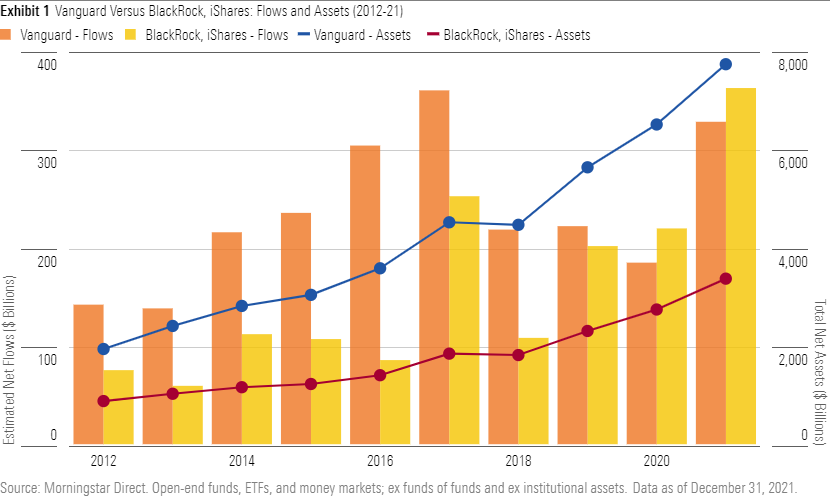

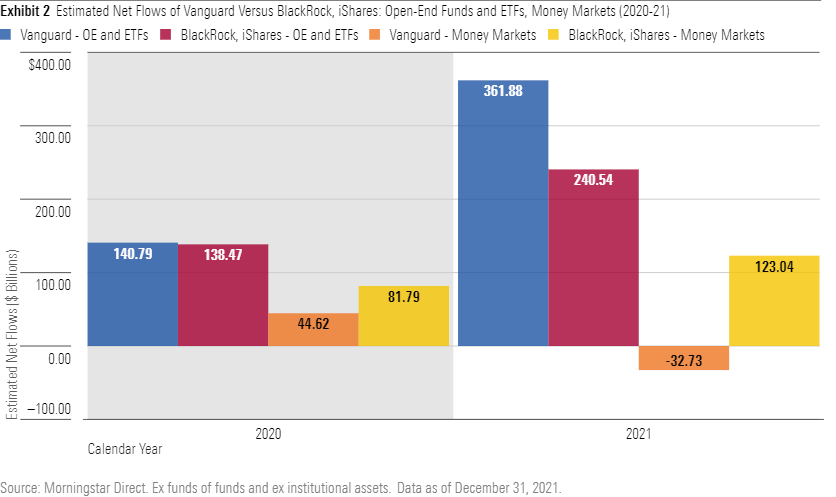

Consider that only BlackRock’s new U.S. retail money flows can compare with Vanguard’s, thanks to their leadership in investors’ current vehicle of choice, the ETF. Also, for two years in a row, BlackRock and its iShares business have edged Vanguard, with others far behind. Including money markets, BlackRock’s 2021 inflows totaled $363 billion, versus Vanguard’s $329 billion. Fidelity finished third with $127 billion.

Yet beneath the surface of what has become a two-way race are signs of Vanguard’s discipline and Bogle’s influence. Although Bogle passed on creating the first ETF in the 1990s because he feared investors would use them to speculate--as many have--Bogle later conceded, “Yes, broad-based stock and bond ETFs, used properly as long-term investments, are good for investors.”[1]

Vanguard’s 56 U.S. ETFs largely lend themselves toward sound long-term investing. Apart from some sector, size- and style-focused, and dividend ETFs, most track diversified benchmarks. BlackRock’s 378 U.S. iShares ETFs include many diversified ones, too, but also lots of niche regional and thematic products, like iShares Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Multisector ETF IRBO, which enable betting on slivers of the market.

Vanguard might have also continued to beat BlackRock’s U.S. retail business on flows had it not been for an investor-friendly but marketing-unfriendly decision. In August 2020, Vanguard renamed its then-$125 billion prime money market fund Vanguard Cash Reserves Federal Money Market VMRXX to signal its narrowed government securities mandate. Rather than risk breaking the buck by chasing commercial paper’s paltry yield, Vanguard changed the fund, which has since seen more than a fourth of its assets withdrawn. Excluding those withdrawals and money markets overall, Vanguard’s flows again outpaced BlackRock’s open-end lineup and iShares ETFs in 2020 and 2021.

Critics Are Right About Vanguard’s Customer Service

Critics are on point about Vanguard's customer service difficulties. Vanguard has sought to nudge its 30 million investors toward digital engagement, but website glitches have sometimes made that difficult. A late-2021 hack of a third-party service provider impaired delivery of statements, confirmations, and tax forms for days. Client holdings and online transactions weren't affected, according to a firm spokesperson. But the problems may have contributed to Vanguard's December inflows being its worst since 2010.

Vanguard’s nonadvisory clients who prefer or need human interaction too often experience long wait times, which has pushed some toward Vanguard Personal Advisor Services for better access. In fact, a Vanguard advisor recently told an acquaintance considering PAS that he was tired of apologizing to callers and complaining to his manager about Vanguard’s poor phone service and tech stumbles.

It's been suggested, but is unlikely, that Vanguard's low-margin products preclude affording the extra costs of higher-touch service for clients who don't pay PAS' 0.30% annual charge. Vanguard could always forgo further fee cuts to raise money. It also sold at reportedly favorable terms $3 billion of private placement debt in 2020 to invest in its business. Vanguard's renewed efforts to improve client experiences since 2017 simply haven't made enough progress.

Vanguard must overcome persistent struggles to meet customers’ needs amid business growth. Indeed, former company leaders have indicated these struggles trace deep within Vanguard’s history, while Bogle’s employee speeches contain many references to them over the years.[2]

Old Vanguard Versus New Vanguard

Vanguard’s historic customer service difficulties are one of many features that temper idealistic portraits of its past, which some use to criticize present flaws and initiatives. Bogle may have mutualized Vanguard at its mid-1970s founding, launched the first retail index fund, and helped spearhead direct distribution, but those moves weren’t purely altruistic. Rather, each occurred during his fierce, career-defining battle with four Boston-based rivals who had ousted him from his CEO role at Wellington Management.[3]

Thus, competitive motivations coloring Vanguard’s initiatives aren’t unprecedented. While two of my prior articles have raised some concerns regarding Vanguard’s private equity entry and high-conviction active Advice Select funds launch, there are also illuminating similarities between old and new Vanguard.

Indexing and Private Equity: Bringing Institutional Approaches to the Masses

Like private equity today, indexing in the early 1970s was an institutional approach. Bogle initially pursued it not because he was hoping to revolutionize the retail world, but because it was Vanguard’s only option. Vanguard was then a fledgling administrative offshoot of Wellington, which alone retained investment management duties in their relationship. Bogle, however, argued to his board successfully (albeit somewhat disingenuously) that as indexing entailed tracking a benchmark rather than picking stocks, it was an “unmanaged” strategy and thus didn’t infringe on Wellington.[4]

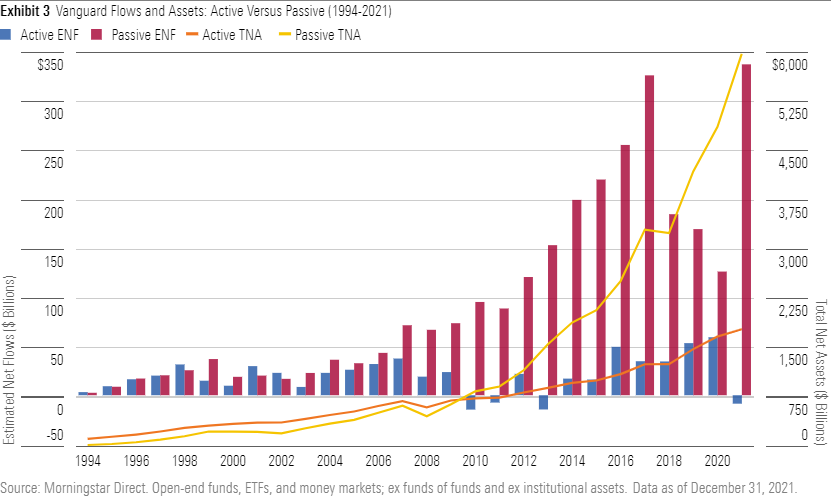

To bring indexing to the masses, Bogle then had to overcome implementation issues, an inauspicious 1976 start, and years of lukewarm interest.[5] In fact, it took until the late 1980s or early 1990s for Bogle himself to transform into a relentless passive crusader, according to a former manager of Vanguard 500 Index VFIAX (initially First Index Investment Trust)[6]. And indexing didn’t catch fire with the broader investing public until the global financial crisis’ aftermath, when Vanguard’s passive assets eclipsed its active assets and grew exponentially thereafter.

Vanguard is also playing the long game with private equity. Its initial private equity plans perished in the aftermath of the dot-com bust, but those experiences likely informed its early-2020 partnership with fund-of-funds purveyor HarbourVest, a firm with more than 30 years in the space. The partnership’s stipulations include an 8% annualized hurdle rate before HarbourVest makes meaningful money and measured asset deployment so that investors won’t have bought in at the top should the PE market implode and struggle for years.

PE's costs and complexity are an obstacle, and capacity constraints limit its democratization potential. Although Vanguard envisions potentially allocating a portion of target-date assets to private equity someday, it and other major target-date providers have yet to take that step. But with Vanguard's own tepid 10-year return expectations for publicly traded equities, it makes sense to look toward a sibling asset class whose returns don't move in lockstep with the public market and begin offering exposure to qualified clients. It would also be irresponsible not to explore broadening opportunities given that private companies can grow justifiably large before turning public, as did Meta Platforms FB (formerly Facebook).

High-Conviction Active: Horizon Funds and Windsor as Forerunners of Advice Select

Vanguard’s three newly minted Advice Select funds resemble its 1995 debut of four high-conviction active Horizon funds on Bogle’s watch. Although he later regretted marketing considerations’ role in that debut, he pointed with pride to Vanguard Capital Opportunity’s VHCAX record, one of the original Horizon funds. It has thrived over market cycles since Vanguard fired the fund’s original manager and turned it over in 1998 to a subadvisor it by then knew well, Primecap.[7]

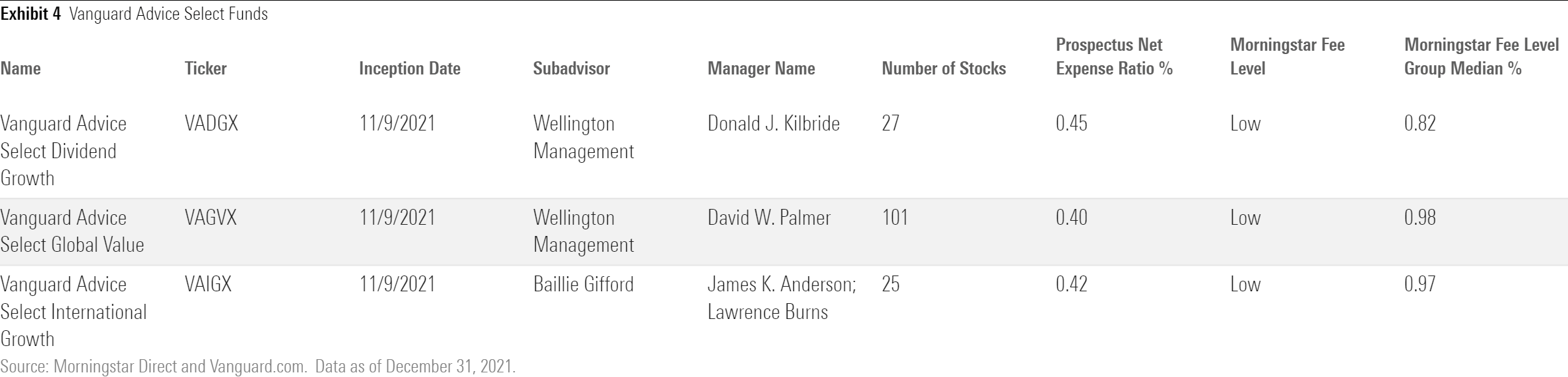

Vanguard took this Primecap lesson to heart. Although new, each Advice Select strategy builds on either an existing or prior Vanguard offering and uses proven investors from two of Vanguard’s most trusted subadvisors, Wellington and Baillie Gifford, as I’ve detailed elsewhere.

The Advice Select funds differ in their exclusivity but otherwise align with key Vanguard values. Reserving them for advisory clients helps keep capacity in check and increases the chances they will be used well, as investors must submit themselves to a risk assessment before they get in. And, if tempted to get out after poor performance, clients must speak with an advisor before potentially selling at a low.

The Advice Select funds are affordable. Including the 0.30% annual advisory charge, each still costs less than its respective peer median.

Finally, despite its passive success, Vanguard has remained committed to active management and has even tolerated highly differentiated portfolios from its most skilled investors. The Advice Select portfolios are also akin to Vanguard Windsor VWNDX when John Neff ran it from 1964 to 1995.

In Neff's last decade, Vanguard Windsor held as few as 50 stocks, and its typical materials sector overweighting reached 20 percentage points versus the S&P 500. Granted, it underperformed in those 10 years, but its results over Neff’s tenure were outstanding. Bogle himself seems to have benefited, as regulatory filings showed Vanguard Windsor was his biggest personal fund holding more than two years after Neff stepped down.[8]

Ideals Intact

No organization is perfect, and that’s certainly true of Vanguard. However, the competitive spirit and ideals of its founder, who became the industry’s conscience, remain more in place than not.

[1] Bogle, J. C. 2019. “Stay the Course: The Story of Vanguard and the Index Revolution.” (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons), P. 112.

[2] Wigglesworth, R. 2021. “Trillions: How a Band of Wall Street Renegades Invented the Index Fund and Changed Finance Forever.” (New York: Portfolio), P. 125. Bogle, J.C. 2002. "Character Counts: The Creation and Building of The Vanguard Group." (New York: McGraw Hill), PP. 69, 73, 103, 107, 108, 128, 147, 158, 221, 222.

[3] Dean LeBaron of early index provider Batterymarch, an acquaintance of Bogle in the 1970s, went so far as to say that the Boston four, not Bogle, “were essentially the founders of Vanguard, because they made him angry enough that he wanted to prove that what they thought was just the tail of the dog was going to wag the dog” (Wigglesworth, “Trillions,” P. 102). See also Slater, R. 1997. “John Bogle and the Vanguard Experiment: One Man’s Quest to Transform the Mutual Fund Industry.” (Chicago: Irwin), PP. 23-106.

[4] Bogle, “Stay the Course,” P. 40. See also Bogle, “Character Counts,” P. 7.

[5] Transaction costs sunk a 1971 attempt to replicate the New York Stock Exchange’s 1,500 issues through equal weighting. And even if a 1973 cap-weighted approach to tracking the S&P 500 proved tenable, institutional accounts trafficked in large sums that didn’t move much. It was thus an open question whether a retail version of the same could work, as dealing with lots of little accounts and daily flows was more complicated, especially with the limited computing power then available. First Index Investment Trust (later Vanguard 500 Index) raised so little money in August 1976 that initially it could afford only the S&P 500’s largest 200 stocks and an 80-basket sample of the rest. Only after a late 1977 merger with another fund did it have enough money to buy all of them, and its assets didn’t exceed $100 million until 1982. See, respectively: Bernstein, P. L. 1992. “Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street.” (New York: Free), PP. 247-248. Wigglesworth, “Trillions,” PP. 110-113. Bogle, “Stay the Course,” PP. 46-47, 58-59.

[6] Wigglesworth, "Trillions," P. 124. Bogle's transformation into the apostle of retail indexing is even more remarkable given that in his Wellington days he argued (under a pen name) on behalf of active management and against the concept of indexing. See Armstrong, J. B. [aka Bogle] 1960. "The Case for Mutual Fund Management." Financial Analysts Journal, V. 16. PP. 33-34, 36-38.

[7] Bogle, “Character Counts,” P. 176. Bogle, “Stay the Course,” PP. 104-105, 200-201, 217.

[8] In March 1998, 38.4% of Bogle's personal $35.2 million portfolio was in index funds; the rest was active, including his biggest single holding: a $4.6 million stake in the stock strategy Vanguard Windsor. See Gould, C. 1998. "An Unusual Window into Vanguard." New York Times.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/08b315db-4874-427f-b3b1-f2b84a16e609.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/08b315db-4874-427f-b3b1-f2b84a16e609.jpg)