Why the Gender Pay Gap Remains Wide

Plus, some advice for women investors.

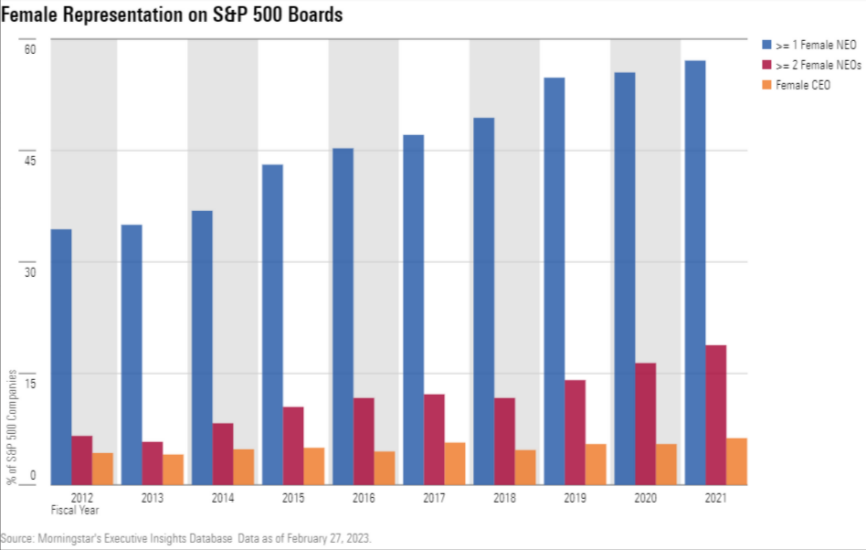

As International Women’s Day rolls around again, we are reminded that more progress is needed to close the gender gap. According to Morningstar, while the number of women at the top of the corporate ladder has inched up, women will have to wait until after 2060 to reach parity with men at the present rate of progress.

This outlook is supported by data from elsewhere. According to Equileap data for 2023, globally, women in top leadership positions are still very rare. Some 6% of global companies have a female CEO, 15% a female CFO, and 8% a female chair of the board. That compares with 5% of companies globally with a female CEO, 13% with a female CFO, and 7% with a female chair the previous year, according to Equileap data.

What Jobs Are Women Doing?

Globally, women represent 28% of board members, 20% of executives, 26% of senior management, and 38% of the total workforce, according to Equileap data. Only 18 companies globally achieved 40%-60% of women at all levels (board, executive, management, and workforce).

Among S&P 500 constituents, women account for 6.3% of CEOs, up from 4.5% in 2012, according to Morningstar Sustainalytics.

What about pay? In 2021, based on 2022 disclosures, women earned a smaller proportion of what their male counterparts earned, says Jackie Cook, director of stewardship at Morningstar Sustainalytics. Variable pay linked to share performance makes up the largest proportion of compensation for named executive officers, or NEOs — the highest rung on the corporate ladder. NEOs who have a larger portion of their pay in variable components generally take home a greater overall sum.

A handful of female CEOs in the S&P 500 consistently outearned their male counterparts on average, according to Cook. Even for the upper ranks, a closer look at the data shows that average female CEO pay is pushed up by super-earners—Safra Catz of Oracle ORCL in 2020 and Sue Nabi of Coty COTY in 2021, for example. For other named officers, the wage gap persisted. “Overall, across all NEOs, women earned only 82 cents for every dollar earned by their male counterparts in 2021,” based on pay data reported in 2022, Cook said. “This is because of the predominance of men in CEO roles.”

To be sure, this isn’t the experience of a majority of the women in the workforce, as CEO pay growth continues to outpace both worker pay and the performance of the broader economy. But while different organizations calculate the gender wage gap differently, the consensus in the results is that women consistently earn less than men, and the gap is wider for women of color. The World Economic Forum’s 2022 Gender Gap Report, which looks at a range of measures including economic participation, educational attainment, health, and political empowerment, points out that at the current rate of progress it will take 132 years to reach full parity.

Why Companies Need to Disclose More Gender Data

Transparency is one way to help close the gender pay gap. But according to Equileap, only 22% of companies globally publish their gender pay gap data (up from 17% in 2022 and 15% in 2021). In addition, disparities in transparency among countries remain huge: 98% of Spanish companies publish their gender pay data, compared with just 12% of U.S. companies. Under SEC rules, companies are not required to publicly disclose workplace diversity metrics or diversity-based pay breakdowns.

Why the Gender Wage Gap Matters

What causes the gender gap? At the top of the corporate ladder, it’s the consequence of bias across practices like recruitment, promotion, employee retention, and talent development. Cook says, “Beyond the traditional ‘glass ceiling’ metaphor, there are other more apt explanations for the gender imbalance at the senior level: ‘glass walls’ that refer to barriers that isolate women by blocking lateral moves; ‘the broken rung’ that refers to the phenomenon where women in entry-level positions are promoted to managerial positions at much lower rates than men; and the ‘leaky pipeline’ that refers to the decrease in the number of women employees at every stage of their career. These concepts speak to the reality that women more often hold positions that don’t take them to the top, don’t pay top dollar, and don’t offer as much of a share in the upside of corporate performance.”

According to McKinsey & Co.’s Lean In survey, only 87 women are promoted from entry-level roles to manager positions for every 100 men. At the same time, the report says, women leaders are leaving their companies at high rates, partly because they are looking for more flexible work policies, and partly because of the headwinds to advancement.

How All This Affects Women and Investing

This creates a set of investing challenges for women, who outlive men by four years on average and must figure out how to save for retirement, often with fewer resources.

As investors, women are often perceived as “‘risk-averse’ or less aggressive than men in investing,” says Morningstar’s director of personal finance Christine Benz. Yet a closer look at the data suggests that women’s lower average incomes—rather than gender-related risk preferences—are the key driver behind their lower average allocations to stocks. Unsurprisingly, people with lower incomes contribute less and invest less in stocks than do higher-income people. But after controlling for income, Benz found that it appears that women contribute as much to their retirement accounts and invest just as much in stocks as men at the same income levels.

“Addressing income differences, and in turn savings rates, especially at lower income levels, is key to healing the gender gap with net worth and retirement savings. Of course, that’s easier said than done. A complex set of factors contribute to the lifetime income gap between men and women—notably, the fact that women are much more likely to serve as caregivers for children or elderly parents than are men,” Benz says.

One way to overcome the investing challenges is through lifecycle financial planning—and investing, according to my colleague, Morningstar Italy’s editorial manager Sara Silano. That’s the process in which different life stages determine specific goals.

Women often have different life stages shaped by education, family, work and aging, Silano says. During each phase, women have distinct needs and preferences that call for an investment approach that supports them in building their wealth and securing their long-term financial independence:

- Age 20-30: Women tend not to have a steady income, but it is important to start thinking about saving for retirement, because in this way they can build their wealth and secure their long-term financial independence.

- Age 30-45: Women may take a maternity break to have and take care of children, so they may need to reduce their earnings and pension contributions, which can lead to wealth setbacks later down the road. Women should ensure that their planning reflects their reduced ability to take risks during this period in order to counteract some of these effects. For example, they can focus on payout strategies.

- Age 45-60: As their careers advance, women look toward a phase in their lives in which they can generate higher income and therefore savings, so they can become more-sophisticated investors.

- Age 60+: Women’s risk tolerance declines as they rely more directly on capital income and predictable cash streams to fund their activities and living costs during their preretirement or retirement phase.

Such planning will help improve outcomes for women—and may help narrow those persistent gaps we think about each International Women’s Day.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/52a57b68-8d99-4364-96af-9ffc6a124531.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/52a57b68-8d99-4364-96af-9ffc6a124531.jpg)