The Best Current Sources of Retirement Income

Treasury bonds, TIPS ladders, or annuities? None are perfect, but each can be useful.

Three Retirement-Income Options

Aside from Social Security and other pensions, retirees may obtain guaranteed income from 1) traditional bonds, 2) inflation-protected bonds, or 3) annuities. For ease of presentation, this article narrows the list to one version of each: 1) Treasury bonds, 2) ladders of Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, and 3) single-premium immediate annuities, also known as lifetime annuities.

(Strictly speaking, only Treasury bonds deliver pure “income,” as TIPS ladders and annuities also return investor principal. But that same argument also applies to Social Security receipts, which are universally called “income.” So there.)

None of these choices is ideal. If retirees could receive guaranteed income by buying additional Social Security payments, which is an idea advanced by Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler, they most certainly should. Lacking that option, however, they must devise an alternative solution.

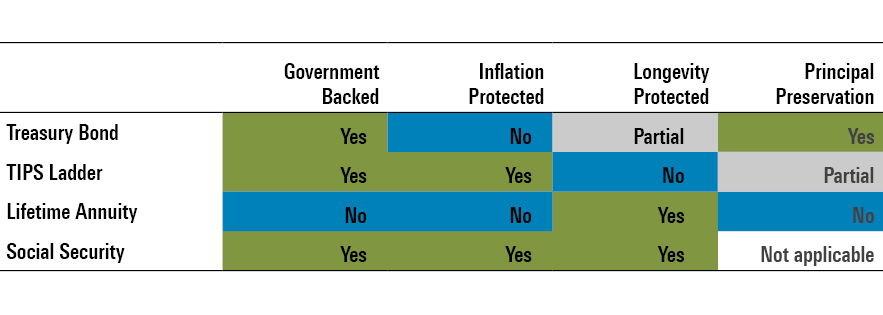

Salient Features

As shown by the chart, Social Security disbursements protect against all major investment-income risks during retirement. They will not default, being impeccably creditworthy. (Never mind debt-ceiling squabbles or debates about Social Security’s finances.) They compensate fully for inflation, as evidenced by their 8.7% cost-of-living adjustment for 2023, a raise far above what American workers received. And, like the Terminator, they absolutely will not stop, ever.

Not so for the investment substitutes. True, each offers safeguards. Treasury bonds and TIPS ladders are backed by the United States government. In addition, TIPS ladders forestall inflation, while annuities ease the danger of outliving one’s money. However, each also has drawbacks. If inflation is high, the value of the Treasury bond and annuity payments erodes, sometimes severely. And TIPS ladders are self-liquidating. When they reach their expiration date, they neither possess assets nor continue their payouts.

For Example

Let’s consider a typical case. A woman who retires at the conventional age of 65 has a life expectancy of almost exactly 20 years. We can therefore fairly compare her return on an intermediate annuity with her receipts from either a 20-year Treasury bond or a 20-year TIPS ladder. (The exercise would be similar for a single man or married couple, but the periods would be 17 and 26 years, respectively.)

The nominal payments for each investment can be easily found. At the time of writing, the yield on a 20-year Treasury bond was 4.05%, the distribution on a 20-year TIPS ladder was 5.89%, and the top annuity rate from a major insurance company for a 65-year female was 7.13%. Unfortunately, those comparisons are apples, oranges, and bananas. They cannot be directly analyzed.

Specifically, the Treasury bond and annuity payments are nominal, while those from a TIPS ladder are inflation-adjusted. Another complication is that each investment’s principal behaves differently. An annuity has no capital worth at all. As previously stated, TIPS ladders are self-liquidating. They retain most of their original price in the early years, reaching zero on their expiration date. Finally, Treasury bonds repay their principal in full.

Good luck evaluating the trade-offs solely through intuition. Besides the investment differences, determining which will be the most profitable strategy also requires answering two insoluble questions: 1) What will the inflation rate be? 2) How long will the investor live? We cannot know those answers in advance. However, we can assess the possibilities.

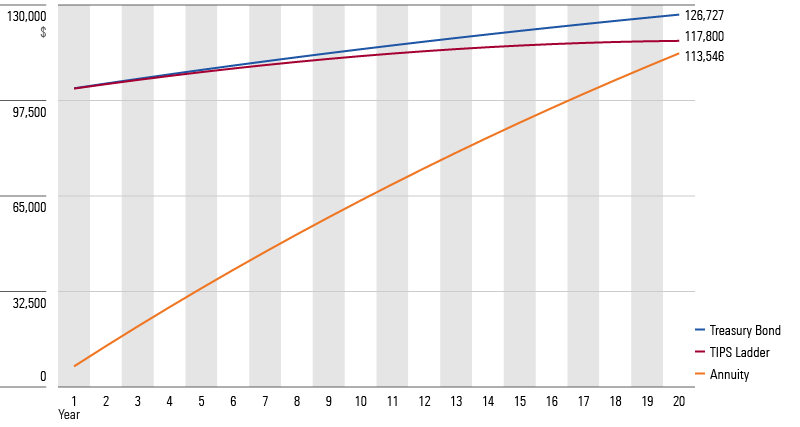

Case 1: Moderate Inflation

The chart below depicts each strategy’s net real return on a $10,000 investment from year 1 through year 20, assuming the consensus long-term forecast of 2.4% average annual inflation. (Technical detail: For this and all future calculations, all payouts are assumed to be spent on the date they are received, discounted by the inflation rate.)

Forecast Inflation

This tale is relatively straightforward. Because the evaluated time horizon extends only to the investor’s average life expectancy, the annuity is unappealing. Its advantage accrues to the long-lived. Meanwhile, Treasury bonds and TIPS ladders have roughly similar results. This happens because the prices of Treasury bonds and TIPS ladders implicitly embed the market’s overall view on inflation. The result could not be otherwise.

(Note: For simplicity’s sake, this column’s calculations use fixed par values for all securities. Changing that assumption would greatly add complexity without altering the general conclusions.)

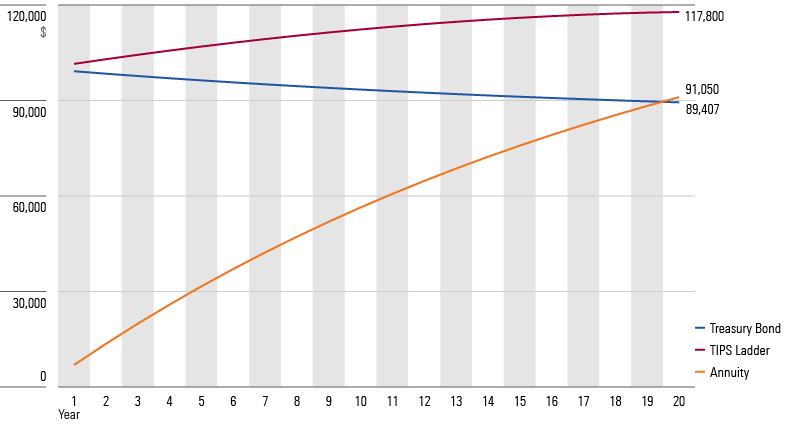

Case 2: High Inflation

The next chart looks quite different. Bumping the 20-year inflation forecast to an annualized 5%, which is less than the nation’s 20-year rate during the 1980s, highlights the strength of TIPS ladders, along with the vulnerability of Treasury bonds. Once inflation takes hold, TIPS ladders move well ahead of Treasury bonds, which in turn fall behind annuities before the 20 years are completed.

With 5% Inflation

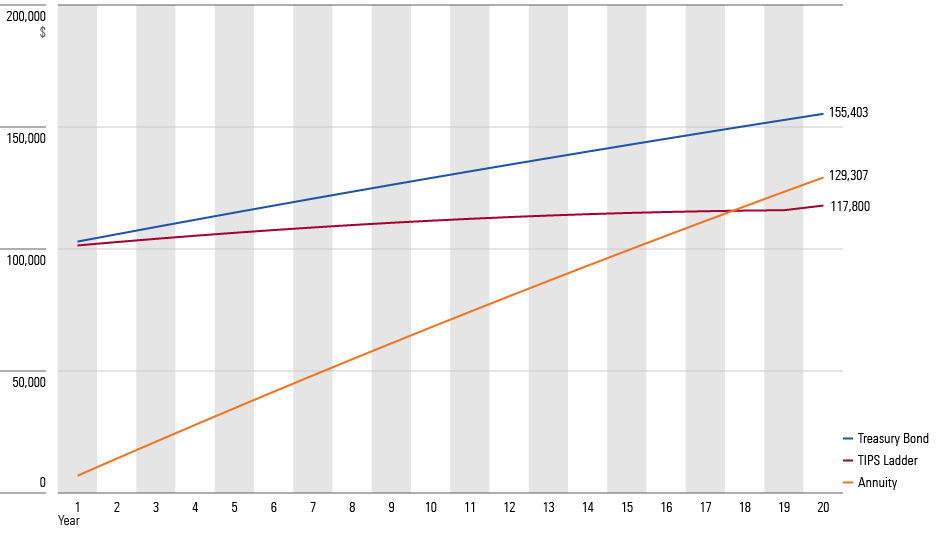

Case 3: Low Inflation

If inflation is low, the outcome reverses. Treasury bonds dominate, while TIPS ladders fall to the rear. With 1% inflation, Treasury bonds not only thrash TIPS ladders over protracted time horizons, but they also are easily ahead of annuities after 20 years. The upshot: Should you somehow know that inflation will be dormant, buy fixed-rate Treasury bonds.

With 1% Inflation

Case 4: Long Lives

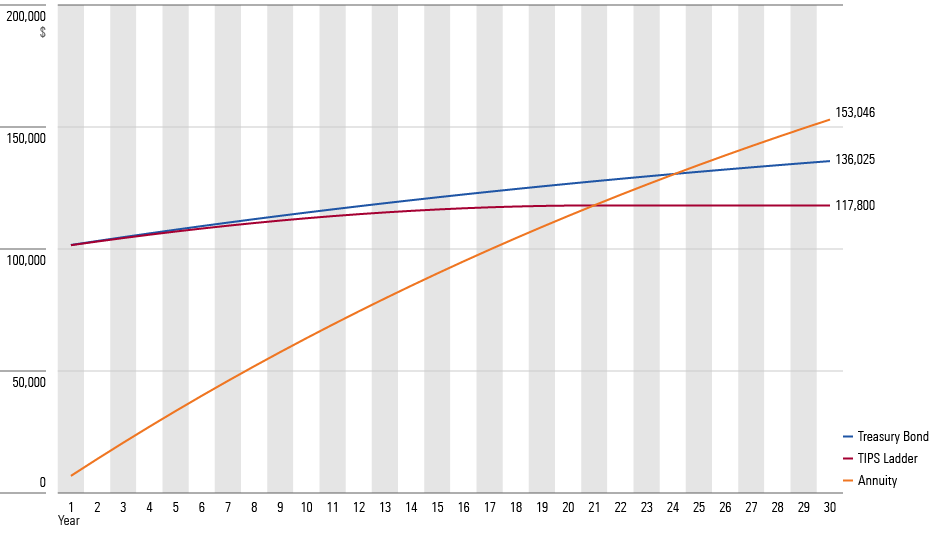

Thus far, annuities have played third fiddle, while the other two strategies have swapped leadership. This comes as no surprise, as the sole reason to buy an annuity is to protect against longevity risk, and the charts thus far have portrayed only short to average life spans. The final exhibit extends the analysis for another 10 years, using the consensus inflation forecast of 2.4%.

Forecasted Inflation, 30-Year Time Horizon

The annuity under that inflation assumption surpasses the TIPS ladder during Year 21, then Treasury bonds in Year 25. Should inflation be pleasantly low, annuities will also prosper, although they will take another few years to catch Treasury bonds. In contrast, they suffer from high inflation but nevertheless remain comfortably ahead of the worst high-inflation investment, Treasury bonds.

Conclusion

For retirees who do not live unusually long, Treasury bonds are superior if inflation is low to moderate, and TIPS ladders are strongest if inflation is high. For those who postpone their meetings with the Grim Reaper, annuities are the soundest overall bet. To be sure, they are vulnerable to high inflation, but (because their payout rates are higher) less so than with fixed-rate bonds.

In short, depending upon circumstances, each of the three retirement-income options could prove the best or worst investment choice. It seems prudent, therefore, to diversify among each. How to make such a decision, of course, is an entirely different topic—a matter for another column.

Living in the Matrix

The film “Flaming Hot” relates, per the subtitle of the book on which it is based, “the incredible true story of one man’s rise from janitor to top executive.” Most notable, we are told, Richard Montañez invented the popular snack, Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. Except … he did not. The “true story” is entirely a lie.

Explains the film’s director, Eva Longoria, “We never set out to tell the history of the Cheeto. We are telling Richard Montañez’s story and we are telling his truth.”

Can somebody lend me a red pill?

Correction: A prior version of this article had an incorrect exhibit for 1% inflation.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)