Bonds’ Pain Is Retirees’ Gain

Fatter bond yields permit higher portfolio-withdrawal rates.

The Silver Lining

One of my salient memories as a mutual fund analyst came when interviewing a bond-fund manager in 1994 after that year’s fixed-income “massacre.” (Little did we know: Compared with bonds’ recent thrashing, that was a sandbox tussle). Other portfolio managers bemoaned the capital losses. Not Dan Fuss. He celebrated his fund’s prospects. Now it could offer high yields, for a long time.

And it did. Each year over the next decade, Loomis Sayles Bond LSBRX paid at least 7% of its assets as income. That occasion reinforced what can easily be forgotten during bear markets: From investment troubles arise opportunities.

A 16-Year High

That bromide merits consideration today, when long-bond yields are 5 times higher than their 2020 trough. The table below shows 1) the lowest yield on 30-year Treasury bonds over the past decade, 2) the average yield, and 3) the current yield. The latter, from Friday’s close, is the highest since July 2007.

Long Treasury Yields

(30-Year Treasuries, Oct. 7, 2013-Oct. 6, 2023)

| Low | Average | Current | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Yield | 0.99% | 2.80% | 4.95% |

| Real Yield (Assuming 2.3% Inflation) | -1.28% | 0.49% | 2.59% |

Accompanying those amounts are the bonds’ real yields, assuming annualized inflation of 2.3%. (Real yields are usually obtained by subtracting inflation from nominal yields. However, I used the true formula, which stipulates division; that is why the numbers do not sum.) By that math, long-bond owners not only settled for a scant gain throughout the decade but at times paid the federal government to hold their money. Now at last, they are receiving a meaningful wage.

Inflation Forecasts

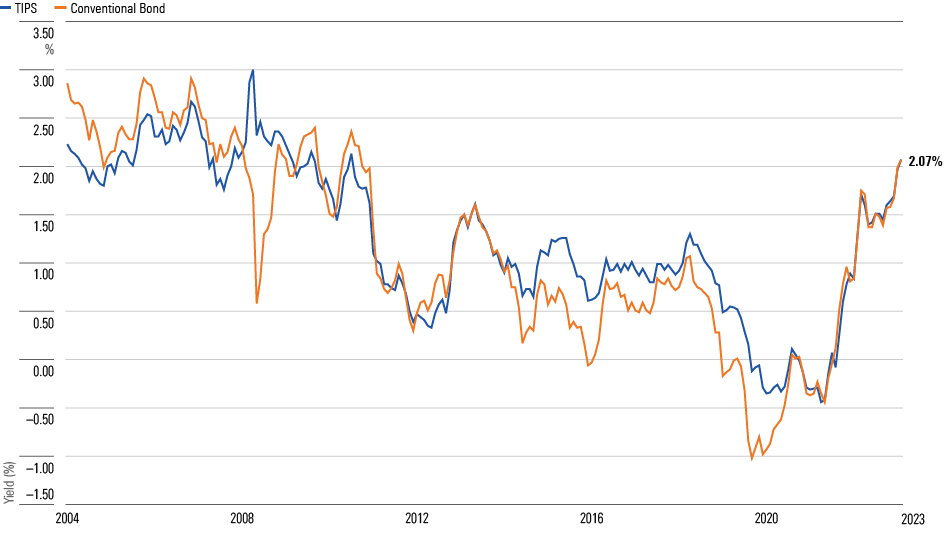

The argument against that proposition is that inflation outlooks are unstable, which makes evaluating nominal yields with a fixed inflation forecast inaccurate. By that logic, Treasury yields have spiked because investors have revised their inflation predictions, anticipating much higher future rates. But that has not been the case. The 30-year Treasury “breakeven rate,” which provides the marketplace’s implicit inflation expectation by comparing the yields on long nominal bonds against those of long Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, has barely changed since May 2021.

Indeed, the marketplace has assumed something close to a 2.3% rate for most of the past two decades. The following illustration compares the yields on 1) 30-year nominal Treasuries with those of 2) 30-year TIPS plus a 2.3% assumed annual inflation rate. (Well, actually 2.29% … it’s a long story.) With the brief exceptions of the 2008 global financial crisis and the late 2010s, the two lines have acted in tandem. The upshot: Real yields on Treasuries have moved much more than inflation expectations.

Real 30-Year Yields: TIPS and Conventional Bonds

Whether the collective is correct in discounting the possibility of high long-term inflation is another question. I confess to being an inflation skeptic myself. Those who feel more strongly than I do about the subject—my distrust is mild—will no doubt avoid long nominal bonds entirely despite their increased yields.

Fair enough. However, there is also logic in accepting the market consensus. For example, in summer 2012 bond yields plummeted, sparking articles that lamented the formation of a “bond bubble.” The concern turned out to be valid for 30-year bonds but not for intermediate-term securities. By the time the forecast bear market arrived, a decade had passed. The notes had matured.

The Payoff

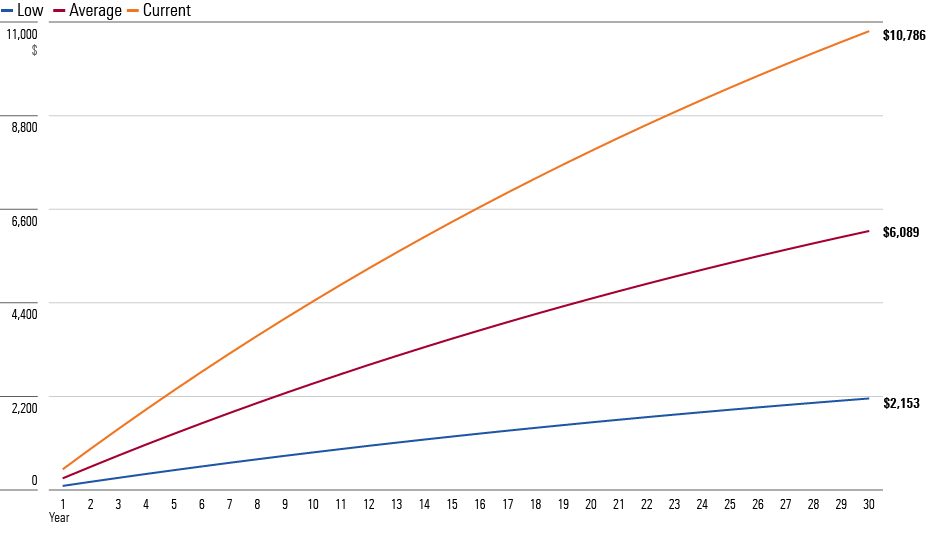

For those willing to trust the wisdom of the crowd, the reward for owning long bonds has greatly increased. That insight, admittedly, is not particularly deep. Still, it’s worth seeing the numbers. The next chart depicts the inflation-adjusted value (using the 2.3% inflation assumption) of the cash received from a $10,000 investment in the three versions of the 30-year Treasury bond—the low yield of 0.99%, the average yield of 2.80%, and the current yield of 4.95%.

Total Real Payments

That is quite the disparity! Investors who buy long Treasuries today will receive more cash than their capital investment after accounting for the effect of inflation. (Once again, that statement is based on an inflation rate of 2.3%.) In contrast, the unfortunates who acquired the same security in March 2020 will collect just 20 cents on the dollar when all is said and done.

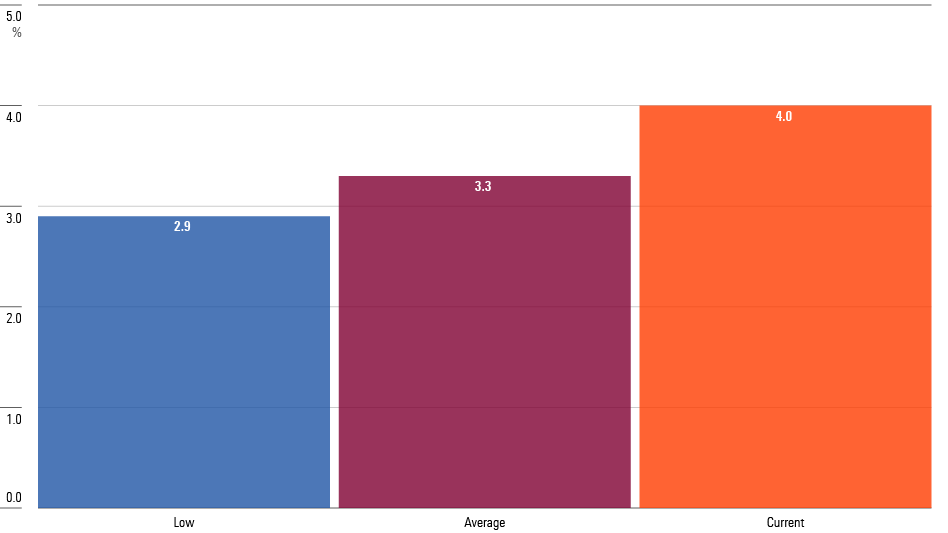

Let’s consider how those yield differences might affect a retiree’s income. For this exercise, I used the model underpinning Morningstar’s annual “The State of Retirement Income” report, which determines the highest inflation-adjusted spending rate that retirees can safely withdraw from a portfolio over the next 30 years. When I plugged the current yield on 30-year Treasuries into the program, it recommended a 4.0% withdrawal rate for a balanced portfolio that consisted of 50% stocks and 50% fixed-income securities.

(Note: This was merely a test case prepared for this article. The next version of the paper, which will be released in November, will carry the official results.)

The Effect on Portfolio Withdrawal Rates

Changing the Treasury bond yields dramatically affected the recommendations. Substituting the average 30-year Treasury yield over the past decade of 2.80% for today’s 4.95% figure slashed the approved withdrawal rate to 3.3% from 4.0%. Using the 10-year low yield of 0.99% further reduced the withdrawal rate to a paltry 2.9%. The bottom line is that, thanks to sharply rising bond yields, retirees are much better off today than they were three years ago.

Wrapping Up

There are two caveats. One has already been addressed: the unreliability of the inflation estimate. The consensus is correct more often than investment pundits like to admit, but it certainly is not infallible. Rising bond yields could indeed reflect the likelihood of greater future inflation rather than the very pleasant circumstance of steeper real yields.

The other catch is that today’s higher yields are immaterial unless investors can take advantage of them. Regrettably, retirees who already hold large positions in long bonds cannot improve their situations. Which brings up another investment lesson: the importance of dry powder. Even though current yields on long bonds look attractive, I would not commit all of one’s fixed-income capital to them. After all, they can always go higher yet.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)