What Investor Biases Are Open Investors Most Prone To?

Contributor Michael Pompian shares the results of his new study of personality traits and investment biases.

This is the 11th article in a series focusing on the Big Five personality traits and how they relate to behavioral biases of investors. Over the years, I have followed a debate between the effectiveness of the Myers-Briggs test versus another widely used personality test, the Big Five. More recently, the debate has intensified, and I decided to conduct a study of the Big Five. Specifically, I studied 121 investors, examining the relationship between the Big Five and investor biases. Why? Because taking the time to understand the underlying personality of the investor leads to better advice and results. This month's article examines openness.

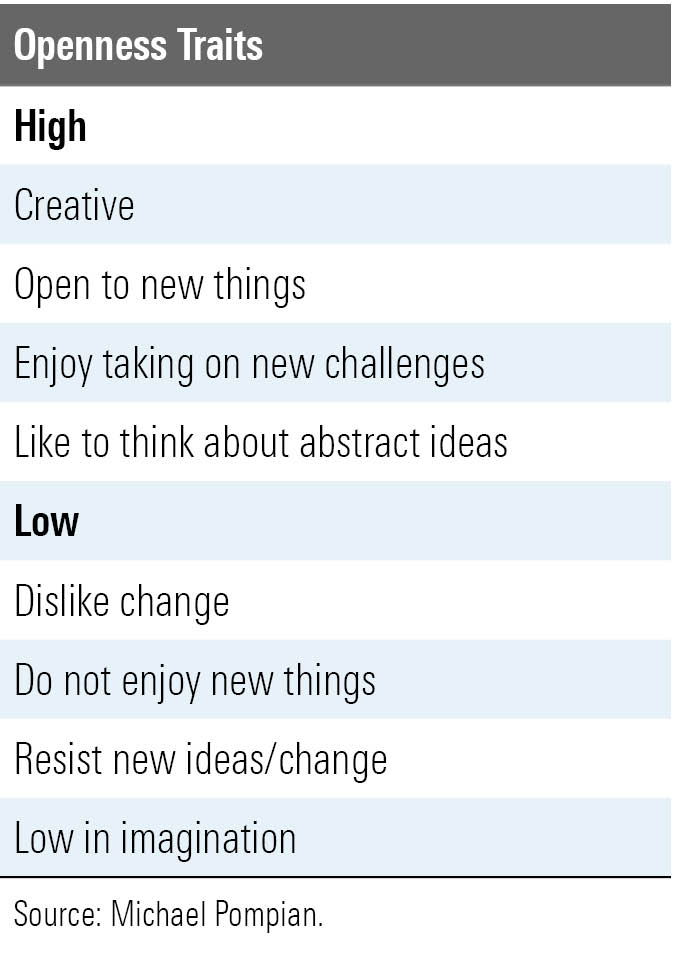

Openness This trait's primary characteristics are imagination, curiosity, and creativity. People who are high in openness tend to have a broad range of interests and skills. They are inquisitive about the world and other people and are eager to learn and experience new things. "Open" people tend to be adventurous and creative. People low in this trait are more traditional and may struggle with abstract thinking.

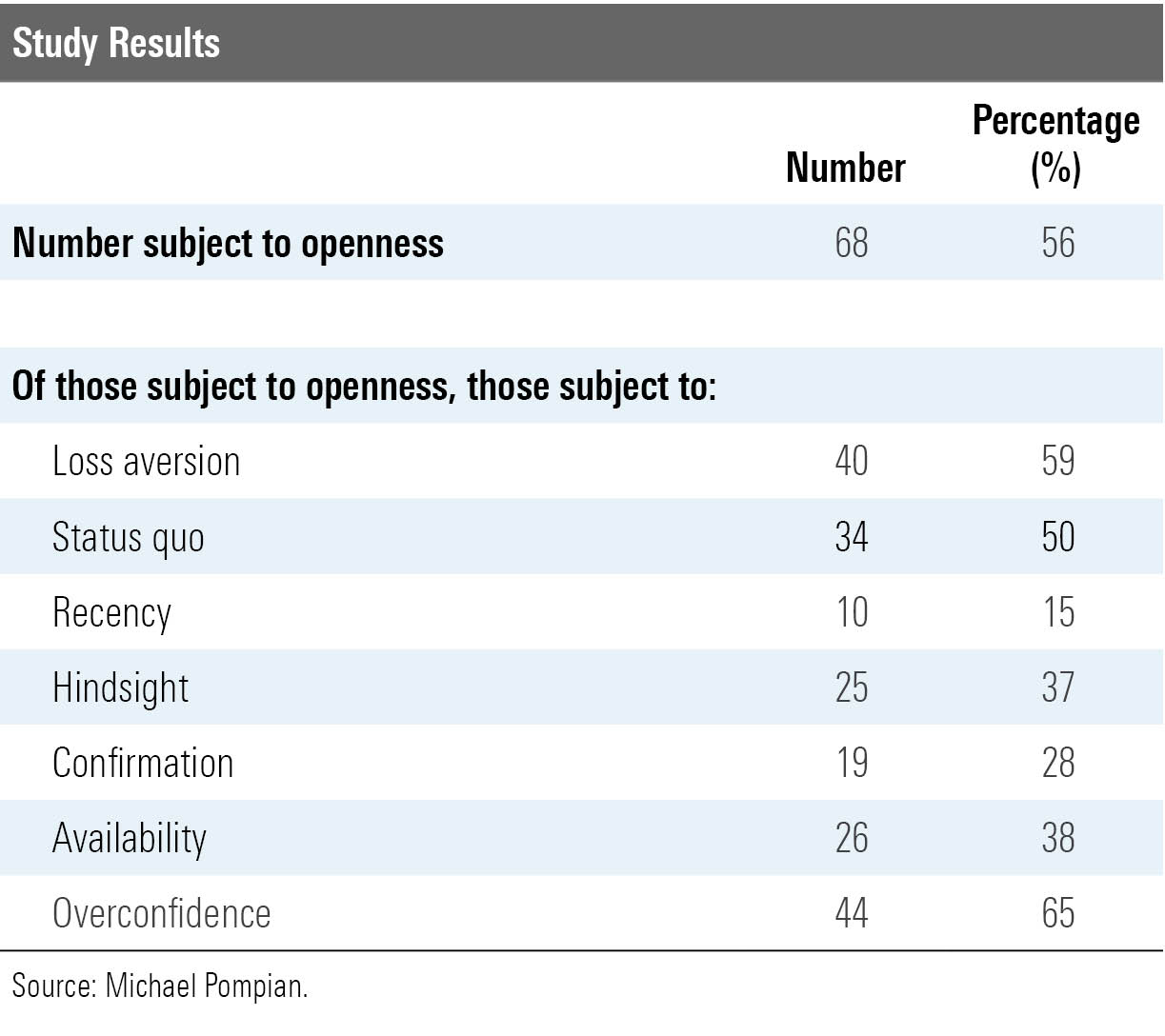

The Study I tested 121 investors for the Big Five personality traits and for the following investor biases: loss aversion, status quo, recency, hindsight, confirmation, availability, and overconfidence.

The results of the study show what percentage of the population surveyed is a) subject to each of the Big Five traits and b) subject to each of the biases. For those personality traits that have a large percentage of respondents subject to a given bias, we will discuss strategies to work with clients on these behaviors. These are the results for openness.

Per the table above, 56% of the 121 people surveyed were subject to openness. Of these 68 people, you can see the percentages of people that were subject to the various biases. The highest percentage was overconfidence at 65%. The next two most common were status quo and loss aversion. We will explore these biases now.

Overconfidence In its most basic form, overconfidence bias is unwarranted faith in one's intuitive reasoning, judgments, and cognitive abilities.

The example of a driver under the influence of alcohol illustrates this. Despite an enormous body of evidence that drinking impairs a person's ability to drive safely and react quickly, drunk people continue to get behind the wheel. If you suggest they shouldn't, the typical responses are "I'm OK," "I can handle it," or "I'm not affected by alcohol like other people." They are overconfident in their abilities to drive under the influence and assume they can beat the safety odds better than everyone else. Similarly, investors exhibiting overconfidence bias overestimate their abilities, sometimes with disastrous consequences. They buy stocks with little or no research, or try to guess the direction of the market without realizing that day to day it cannot be predicted.

Advice: I have seen overconfidence in action many times. To counteract this behavior in my clients, I often recommend they establish "mad money" accounts. This involves taking a small portion of one's wealth for "overconfident" trading activities while leaving the remainder to be managed in a disciplined way. This approach scratches the itch that many investors have to trade their accounts, while at the same time keeping the majority of the money intelligently managed.

Status Quo Status quo bias is an emotional bias that predisposes people facing an array of choices to elect whatever option ratifies or extends the existing condition (that is, the status quo) in lieu of alternative options that might bring about change. In other words, status quo bias operates in people who prefer for things to stay the same. There have been numerous studies testing the idea that people would rather leave things the way they are instead of making a change. These studies have been performed in the realms of politics, ethics, health, and investments, to name a few.

For example, a study was completed with patients taking a certain medication for asthma, and they were offered the chance to try a new medication with potentially better effectiveness. Most participants in the study decided to stick to their original medication instead of trying the new one. Why? In some ways, the status quo bias can be boiled down to the adage of "the devil you know versus the devil you don't." Sometimes we humans stick with things even though we know they may be flawed. This, of course, is not a rational way of behaving.

Advice: I have a status quo bias problem I am dealing with. Until recently, the 60% S&P 500 stock and 40% bond blend performed extremely well for about a decade. Why would anyone have wanted to change their position on this asset mix? The reality is that both asset classes became expensive over that same period of time--and perhaps clients should have considered some changes. This illustrates the danger of status quo. Without warning, the outlook for a given investment can change, and we as advisors need to be ready. Because status quo bias is an emotional bias, it is exceptionally strong and is often difficult to overcome. Educating your clients is essential to overcoming this bias.

Loss Aversion There are many facets to loss aversion, but the most basic and important aspect is that investors feel the pain of losses more than the pleasure of gains, and they will go to potentially irrational lengths to avoid losses.

Imagine you've taken your friend out for a birthday dinner. When you get home, you look at the bill and discover that the waiter charged you twice for the $10 slice of birthday cake that you bought your friend. You immediately call the restaurant back but get voicemail. You decide to call the next day and get a refund. Now imagine the same scenario, but instead of getting charged twice you discover that the restaurant didn't charge you for the birthday cake. Do you call the restaurant? Do you track down the manager the next day because you simply must say "thank you?" Probably not. Why?

A number of studies on loss aversion have given birth to a common rule of thumb--psychologically speaking, the possibility of a loss is, on average, twice as powerful a motivator as the possibility of making a gain of equal magnitude. That is, a loss-averse person might demand, at minimum, a $2 gain for every $1 placed at risk. In this scenario, risks that don't "pay double" are unacceptable. While people are risk-seeking in the domain of losses, they prefer not to take risk in the domain of gains. A rational person, however, would be indifferent between these domains of gains and losses.

Loss aversion is widespread among investors and is probably the most common bias of all. Investors will often sit with losing investments for long periods of time to avoid taking losses and moving on. Beware that this is one of the worst strategies, because holding losing investments for too long can be harmful to your clients' investment health.

Advice: An effective remedy for this affliction is to ask your client, "If you were starting with fresh cash, would you buy this investment?" If the answer is no, then ask your client, "Why would you want to hold the investment?" This is normally enough to cause a change in your client's decision-making pattern. Step two is to find a higher-returning investment (something with good prospects) and ask your client if he or she would rather have that investment than the losing investment. Again, this usually works well to change this type of behavior.

Michael M. Pompian, CFA, CAIA, CFP is an investment advisor to family office clients and is based in St. Louis. His book, Behavioral Finance and Wealth Management, is helping thousands of financial advisors and investors build better portfolios of investments. Contact him at michael@sunpointeinvestments.com.

The author is a freelance contributor to Morningstar.com. The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect the views of Morningstar.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)