The Power of Compounding: Manhattan, Alaska, U.S. Stocks, and Gold

Can anything grow at a double-digit rate over the centuries?

Beyond Manhattan Friday's column calculated the annualized capital growth on Peter Minuit's $24 purchase of Manhattan as 6.7%. Total return, which includes the effect of income along with capital growth, is the better investment measure, but we cannot compute Manhattan's total return. We do not know what profits the island's properties have generated for owners over the past four centuries.

That 6.7% figure seems low. After all, U.S. stocks routinely post such gains, and more. But we live in extraordinary times. The S&P 500’s annualized capital growth for the trailing decade has been 14%. Forget about earning anything like that for the truly long haul. In 1819, many American companies were worth more than $1,000. However, none today are worth anywhere near $240 trillion, which is the value of $1,000 compounded at 14% for 200 years. The feat has never been done.

Writing Friday’s article sparked my curiosity. Despite its seemingly modest growth rate, Manhattan is commonly regarded as having been a great buy (which it was). So, I wondered, what have been the returns on two other legendary purchases: 1) Seward’s Folly, and 2) American equities? As well as gold, for comparison’s sake.

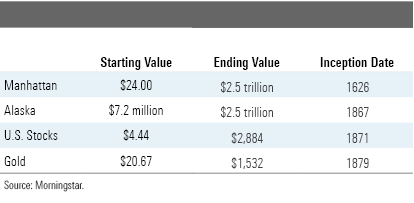

Assembling the Data Each of the four investments' starting values, ending values, and inception dates are shown in the table below. Manhattan's and Alaska's track records begin when they were acquired; the index for U.S. stocks starts in 1871, which is the initial year of Professor Robert Shiller's data set; and gold debuts in 1879, when the United States resumed the gold standard after suspending it for two decades.

The purchase prices are known for three of the four assets. The exception is Manhattan, which couldn't have sold for $24 because the U.S. dollar did not exist. However, we shall abide by the story. No current quotes, of course, are available for either the city or state. I determined their values from Internet surfing. (Not much of a source, but, as Manhattan and Alaska don't trade on exchanges and don't attract competitive bids, one must take what one can get.)

Which asset has grown the fastest? Is it better to have appreciated to $2.5 trillion when starting with $24 in 1626 or when starting with $7.2 million in 1867? Intuition fails. The two real estate deals look to have posted the highest returns, then stocks, then gold. Of that I am reasonably confident. Whether Manhattan or Alaska prevails, though, I cannot say.

North to the Future The answer, it turns out, is Alaska. Its annualized capital growth has been 8.7%, followed by Manhattan at 6.7%, U.S. equities with 4.5%, and gold at 3.1%. For capital growth, the state possessing the industrial commodity performed best, then the city that holds commercial property, then corporations (as represented by equities), and then the nonindustrial commodity. Perhaps this indicates something about asset allocation.

I think it does. If nothing else, the results demonstrate that gold--as well as any other nonindustrial commodity--is an insurance policy, not an investment. Annual inflation from 1879 through 2018 averaged 2.3%. The real capital growth of gold, therefore, was less than 1%. Worse, gold not only delivered no income also required protection. After its cost of insurance, gold would have been fortunate to break even.

True, the time period doesn’t flatter gold. Its price barely moved for the first 80 years, before leaping to $600 from $39 in a single decade. A quarter-century later, it would enjoy another decade-long surge, albeit after losing value along the way. But taking such short bursts as indications of future performances, when a much longer and less optimistic history exists, would be rash--particularly as gold has handily outgained silver.

Considering Income The outcome also suggests that, even when unleveraged, real estate can outgain equities, although that tale requires a major asterisk. That Manhattan and Alaska have been among the happiest-ever land purchases doesn't spoil the analysis because U.S. stocks have been similarly fortunate. This performance contest features the blessed against the blessed. The problem lies with that missing component: income. We lack payout data for real estate, but we possess them for U.S. equities, and they cannot be ignored.

Because the effect is huge. When dividends are considered, thereby turning the capital-growth calculation into total return, the annualized rate for U.S. equities doubles, to 9.1% from 4.5%. Once again, the computation is difficult to visualize. Doubling the annualized rate over a 148-year period will do far more than double the cumulative total--that much is certain. But how much more? Once again, intuition fails. Microsoft Excel, however, does not. It shows that when dividends are reinvested, the value of the U.S. stock market investment swells by 61,073%. (That is not a typo.)

In short, U.S. equities with dividends reinvested have slightly bested Alaska’s capital growth, even after that state was purchased for a relative song and subsequently found to have large amounts of gold and even larger oil reserves. And they have easily outshone Manhattan’s.

Who Wins? How the three investments would rank for total return, if historical income could be found for Manhattan and Alaska, is anybody's guess.

Here’s my view. Aside from the gold rush, Alaska’s income was modest for the first 100 years of its history. Its total return, therefore, isn’t much above its 8.7% capital-growth rate. In contrast, Manhattan has created substantial income for its property owners, though not much in its early years. Overall, a 2.5% annual average for its complete time period doesn’t seem unreasonable. If so, that would also place Manhattan’s total return near 9%. My tentative conclusion: The contest is a three-way tie.

Over the very long term, a 9% total return--that is, 6% to 7% after inflation--is about as good as it gets. One can beat the odds for several years, perhaps even several decades, but ultimately the barrier falls. As for assets, it seems that either real estate or equities can accomplish the task.

Oh, Canada If last Tuesday's column didn't convince you that the Canadian fund marketplace operates in a different century, perhaps this article will: "Why low-fee investment products are bad for you." Published this very week, it admonished against being fooled by advertisements for cheap mutual funds. "Far too often, returns get overlooked by investors as they get sucked into the low-fee story narrative. Don't let this be you."

It has been a long time since I have heard such a thing in the United States.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)