Holding Bonds Under the New Tax Law

Investors should adopt a dynamic location optimization strategy.

Interest rates are going up, and tax rates are going down. What does this mean for bond investors? Should investors still own bonds? And, if they do, how do the new tax laws affect how and where they hold bonds? In this column, I’ll start with the basics and then move on to strategies and recommendations.

Bond Basics It's common knowledge that when interest rates rise, bond values decline. So, in a time of rising interest rates, many investors believe that they shouldn't own bonds. This is not a good decision for several reasons:

- Bonds are negatively correlated to stocks.

- The stability of interest payments can be a saving grace in down equity markets.

- If bonds are held to maturity, absent default, any interim valuation losses are "illusory."[1]

- As long as bonds are not too far out in duration, higher interest rates should not have a significant impact on value.

- As current bonds mature, new bonds will pay a higher rate of interest.

A truly diversified portfolio will contain various classes of bonds, including U.S. core bonds, U.S. government bonds, mortgage-backed bonds, high-yield bonds, municipal bonds, international bonds, and emerging-markets bonds.

Each bond class carries different risk characteristics, tax treatment, and return expectations. Thus, tax considerations must be viewed based on both common and individualized aspects of each type of bond.

Bonds and the New Tax Laws Although the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 made significant changes to the tax laws, the basic taxation of bonds remains unchanged: Non-muni interest is taxable as received (or accrued—as in the case of zero-coupon bonds) and gains and losses are recognized when the bond is disposed of (or redeemed). Current tax laws affect bondholders in the following ways:

- Taxable interest is taxed at ordinary tax rates.

- Taxable interest and capital gains may be subject to the 3.8% Medicare surtax (depending on income level).[2]

- Taxable interest and capital gains are part of adjusted gross income, which reduces deductibility of medical expenses.

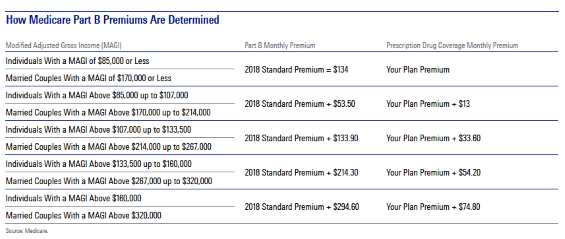

- Taxable interest, capital gains, and tax-exempt interest are part of modified adjusted gross income, which, if in excess of certain levels, can increase the cost of Medicare Part B premiums. (See exhibit.)

The bottom line is that non-municipal-bond interest is taxable annually at ordinary rates— and may have additional negative financial impacts because of decreasing medical expense deductions, subjecting the taxpayer to the Medicare surtax and increasing Medicare Part B premiums. Thus, the federal tax rate on bond interest can be as high as 43.575% (37% plus 3.8% plus 2.775% for the net medical expense reduction), plus any Medicare premium increases.

Tax-Reduction Strategies Managing investments at the household level (across accounts) provides an opportunity to create tax savings with location optimization by holding specific types of investments in different accounts to minimize tax costs. This tax-aware strategy is typically based on a static set of assumptions. After the new tax act, there could be a case for a dynamic location optimization.

Traditional location optimization organizes accounts into three types: taxable accounts such as joint accounts, trust accounts, and personal accounts that are subject to tax as income and gains are recognized; tax-deferred accounts that will be subject to ordinary tax rates as amounts are withdrawn, such as IRAs, SEPs, 401(k)s, other retirement accounts and annuities; and tax-free accounts such as Roth IRAs.

In an established location optimization strategy, investments are divvied up as follows:

- Investments with the highest expected returns, such as emerging-markets equities, should be held in the Roth IRA. Because the Roth will likely be the last resource tapped in retirement, it can withstand volatility. And because the Roth will never be taxed, higher-returning investments will get the greatest benefit.

- Investments that produce regular ordinary income, such as taxable bonds, belong in tax-deferred accounts. This defers tax on the income. When the money is eventually withdrawn, it will be taxed at ordinary rates— the same as if held in a taxable account. As an added benefit, because high-yielding investments such as bonds tend to have lower expected returns than equities, the required minimum distributions will be lower than if higher-appreciating equities were held in the account.

- Appreciating investments, such as equities, go in the taxable accounts. Because appreciation isn't taxed until sold, these assets effectively achieve tax deferral without being held in a tax-deferred account. When eventually sold, the appreciation will be taxed at capital-gains rates. Holding these assets in an IRA (or other tax-deferred account) would convert the low capital-gains tax rate to the higher ordinary tax rate. Also note that if appreciated investments are held in a taxable account at death, the basis step-up will permanently avoid tax.

Based on the traditional static location optimization strategy, once asset types are placed in appropriate accounts, the decision is never revisited. This approach can be counterproductive in times of volatile market conditions and ever-changing tax laws.

For example, most investors who practice location optimization hold U.S. bonds in tax-deferred accounts. However, with the surtax on net investment income and municipal bonds often paying interest almost equivalent to (or even more than) corporate bonds, should we be locating (and investing) differently? Depending on an investor’s particular tax situation, it might be more advantageous to own municipal bonds in taxable accounts and place higher-yielding bonds (such as emerging-markets and high-yield bonds) in tax-deferred accounts.

This dynamic asset-location strategy (based on relative municipal- versus taxable-bond returns and tax implications) could require repositioning trades as market or tax conditions change. Therefore, the costs of repositioning, such as transaction costs and tax costs, need to be considered. If repositioning will result in taxable gains, the following questions should be considered:

- How material is the gain?

- Does the investor have capital losses to offset or are they in a low tax bracket?

- How old is the investor? (Appreciation will likely be taxed at some point for a young investor. In this case, paying tax now would just be a timing difference. However, an older client might never pay tax on the appreciation. Thus, recognizing gains for an older client would make the tax cost too steep.)

- Will the reduction in taxable investment income be greater than the tax on recognized gain?

To maximize tax benefits, investors must embrace dynamic location optimization, while periodically reviewing underlying assumptions. When choosing where to locate a given class of investments, one must:

- Compare municipal-bond yields to taxable yields.

- Revisit the ordering of investments on a scale from least tax efficient to most tax efficient considering the impact of new tax laws.

- Consider individual investor circumstances when determining whether or not to carry out repositioning trades.

Despite rising interest rates and new tax laws, bonds should still be a part of a well-diversified portfolio. To make the most of bond investments, tax impacts—especially location optimization—should be considered.

[1] Value declines are meaningless unless bonds are sold before maturity. The investor will continue to receive interest payments (at lower than market rates) and will receive full face value at maturity. This concept is often cited as a reason to invest in laddered bonds. However, if maturing bonds are continually replaced with new bonds, this strategy is essentially equivalent to bond mutual funds.

[2] The Medicare surtax applies when individuals have net investment income combined with modified adjusted gross income over the following thresholds: married filing jointly: $250,000; married filing separately: $125,000; single: $200,000; head of household (with qualifying person): $200,000; qualifying widow(er) with dependent child: $250,000.

This article originally appeared in the August/September 2018 issue of Morningstar magazine. To learn more about Morningstar magazine, please visit our corporate website.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/256953a9-ba08-4920-baa8-ccdc229ed9f9.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/256953a9-ba08-4920-baa8-ccdc229ed9f9.jpg)