Rekenthaler: My Asset Allocation

Morningstar's John Rekenthaler explains why he is comfortable with owning stocks, stocks, and more stocks.

Close to Home Over the years, readers have requested that I discuss my portfolio. I've resisted those entreaties until now, because I've had difficulty finding the right angle. "About me" doesn't cut it.

But I think I have found something useful. We all know the conventional investment wisdom: Invest heavily in stocks while young, then gradually move to mostly fixed-income with age; diversify broadly; don’t own company stock; minimize costs. How does that advice translate to this rather unusual case, of an investor who makes his career writing about the topic? Which aspects of the conventional wisdom has he incorporated and which has he bypassed? In the latter case, were the decisions logical, or does the cobbler wear bad shoes?

This column covers asset allocation; Friday’s will discuss security selection.

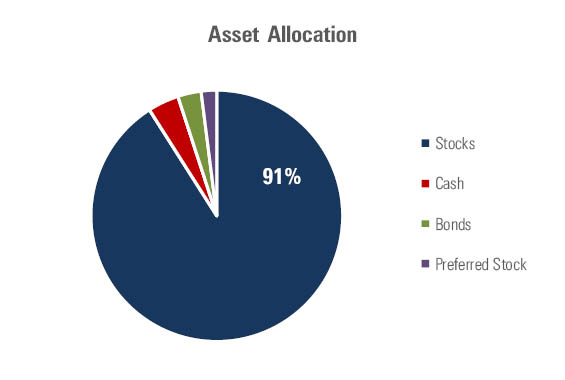

Below is my current asset mix. It consists of 91% stocks, 4% cash, 3% bonds, and 2% preferred stocks (which despite their name, can be regarded as bond substitutes).

That is a large equities position by any standard. The rule of thumb that an investor’s stock percentage should be 100 minus age indicates that my stock percentage should be 44%. (No bonus points for guessing my age from the information.) The most aggressive of professionally managed target-date funds hold considerably higher weightings for their 50-something shareholders, with the largest equity weightings exceeding 70%. Still, that’s far short of my 91%.

By the Numbers Why the difference? To start, while Wall Street oversells the danger of outliving one's assets, because it benefits from instilling fear, there's truth to its claim that today's retirees live longer than their predecessors. They do; and this particular future retiree hopes to be among that number. Wall Street's default suggestion of planning until age 95, with the assumption of living 30 years while in retirement, seems a tad ambitious. But expecting to be around, and perhaps active, at age 85 does not. That gives me almost three decades.

Which, I am delighted to report, is quite a long time—and greatly favors equities. Test various asset allocations over the past century’s history (or longer, if you have the data), in whatever developed country that you like. Reduce stocks’ returns so that they will be lower in the future than they were in the past, and do the reverse for bonds. Measure investment success as you wish. It matters not. For 30 years, the numbers will always favor a high-equity portfolio over a balanced approach.

By “always,” I mean “in every way.” If the financial markets behave very well over the next three decades, the ending balance for the stock portfolio will be much, much larger than for the balanced portfolio. If the markets perform adequately, the stock portfolio will also prevail. If the markets disappoint, stocks will at worst match the balanced portfolio’s results. And if the markets are catastrophically bad, because the nation loses a major war and/or inflation skyrockets, stocks will win easily—because in such cases, bonds often go to zero, while stocks do not. The numbers over the long term always favor equities.

Accumulating Versus Withdrawing There are two possible objections to this argument.

One is that the final 20 years of my time horizon involve withdrawals. And withdrawals are a different beast altogether. An asset pool that is accumulating, without being touched, can withstand any bear market without damage, assuming that those securities eventually recover to their previous levels. An asset pool that is being used for withdrawals, however, can and will suffer permanent damage. In funding its cash payments during the down times, that pool sells its securities low. That those securities later recover their losses does the investor no good at all.

This objection is valid, but overstated. It is true that if a severe bear market arrives early during the retirement period, and the investor does not adjust the withdrawal amount, the equity-heavy portfolio gets whacked. The balanced approach shows its benefits.

However, this analysis carries the twin assumptions of investor inflexibility and a reasonably high withdrawal rate. If those assumptions do not hold, then the retiree can ride out the storm. She or he can hold off withdrawing significant assets during the worst parts of the downturn, so that the portfolio sustains minimal permanent damage.

A friend, for example, informs me that when his retirement begins (whenever that might be, he is 70 years old now and going strong), his annual portfolio withdrawal rate will be less than 1%, and that amount includes luxuries that he can do without. Clearly, he need not worry about damaging his nest egg by withdrawing at the wrong time. My financial situation is not

that

strong—but it is very good, given my

absurdly lucky decision to join an 18-person startup that would eventually become a $3.4 billion company.

Thus, under most conditions, my retirement portfolio will grow rather than shrink, and therefore can be treated as (mostly) being in the accumulation stage. That happy condition could change. The financial markets could crumble badly, for a long stretch of time, and/or my spending needs could skyrocket. But unlike with most simulations, people can adjust their plans—which for me, would mean swapping for bonds.

Staying Smart The other objection to (almost) all equities is that the math might be fine, but the behavior is unrealistic. Investors don't necessarily wait patiently through the downpours, confident that the sun will soon reappear. They often sell. Or, in equally damaging if less dramatic fashion, they stop putting new monies into risky assets, which means that they don't receive all the benefits of the recovery. What makes me think I would be different?

That is a good question; the issue is my greatest concern. I have no doubt that under certain investment conditions, I could make bad, emotional decisions. Those who study psychological mistakes tend to make fewer such errors, but they are by no means immune. Doing something stupid is an ongoing danger, for me as well as for others. (Morningstar’s Don Phillips likes to say, quite accurately, that investment excellence comes from “avoiding avoidable errors.”)

That said, I have been invested now for 30 years, and meaningfully so (with a portfolio that was large enough to matter) for the past decade. That included the very bad year of 2008, which was particularly difficult for me, since at that time my portfolio consisted almost entirely of Morningstar stock, which fell 70% from peak to trough. I was less than enthralled, but not tempted to sell.

Thus, I believe that my asset allocation has been well conceived. It varies from the norm, but with good reasons. In my view (yours may certainly differ), the cobbler wears the right shoes. As for Friday’s subject of security selection … not so much.

Note: Morningstar’s Alec Lucas objects to my comment that “numbers always favor stocks” over a 30-year time horizon. As he should. My statement reads as a claim that a stock portfolio inevitably beats a balanced portfolio, over all 30-year periods. That is emphatically not true. There have been many instances in which a balanced portfolio has outgained stocks over 30 years. What I had intended to convey, but failed to do so because of poor wording, was that when researchers run simulations, they generally conclude that an all-stock portfolio is a better bet than a balanced portfolio. This holds true across various market conditions: bull, neutral, bear (although that case can be argued), and catastrophic. The argument is not that stocks always win with any particular draw, but rather that the odds always favor the stock portfolio. That section would have been clearer if I had written “odds” instead of “numbers.” Sorry about that.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/05-08-2024/t_f17f0449d3314a27b966dcee5d39a6cb_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LUIUEVKYO2PKAIBSSAUSBVZXHI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BNHBFLSEHBBGBEEQAWGAG6FHLQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)