Job Growth Slowdown No Big Surprise

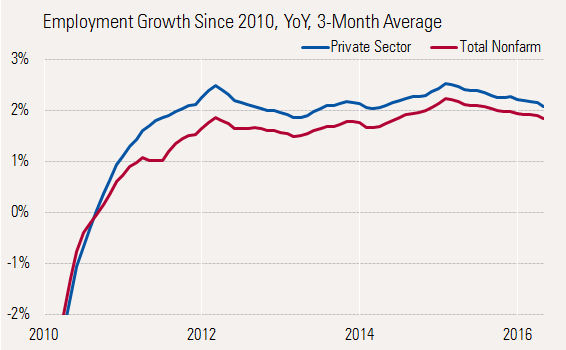

Employment growth had been running higher than fundamentals dictated since at least last fall.

This week's employment report was the key economic data point, and it dwarfed just about everything else. Slowing employment growth comes as no surprise to us, but the fact that the slowdown showed up in May, in full force, didn't make a lot of sense. While the report was terribly inconsistent, job growth had been running higher than fundamentals dictated since at least last fall. Some type of adjustment was long overdue.

Markets didn't react strongly to the report, as worries about economic weakness engendered in the employment report were offset by hopes that a Fed rate increase would be pushed off to the distant future. With employment being one of their two key focus issues at the Fed, it can hardly raise rates now, without seemingly going back on its word.

The employment report overshadowed the exceptionally strong consumption growth reported early in the week, showing monthly growth of close to 1%. We hope and believe that the slowing employment report was lagging real-world performance data that has turned mainly positive. Purchasing manager data registered another improvement, suggesting that the manufacturing sector continues to trudge along with little growth but no deterioration, either.

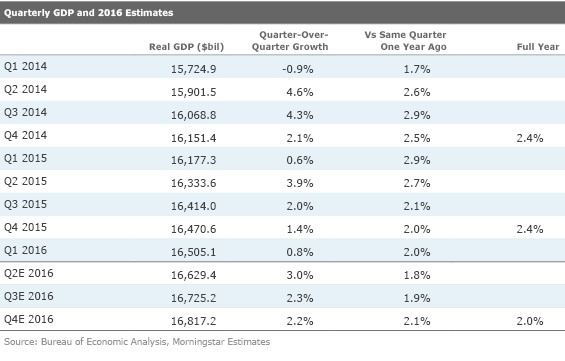

Massive revisions in first-quarter trade data and construction data suggest that the 0.8% GDP growth rate may get a large, perhaps massive, upward revision next month. However, those data revisions to the first quarter mean that the April data showed unfavorable trends. So the messages on construction and trade were decidedly mixed.

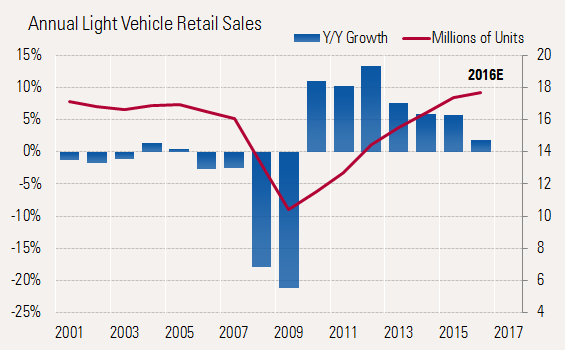

Auto data was also soft. Like the employment data, we had been forecasting weaker auto sales for so long, with little real-world deterioration, that we were surprised when the weakness magically appeared in a single month. Year-over-year auto sales fell by over 1% in spite of higher incentives and more attractive leasing programs. The slowing appears to be more of a saturation issue than a consumer sentiment problem.

Slowing GDP Growth Finally Hits the Employment Market May's employment report looked dismal on the surface, showing that just 38,000 jobs were added during the month. Low initial jobless claims, the job openings reports, stronger recent economic data, and a near record-low Challenger Gray lay-off report were not consistent with the May employment report. Even within the official report, there were a lot of nonsensical data points. Work hours were flat and hourly wages were up and manufacturing overtime hours remained elevated. None of these is consistent with a report that showed the lowest number of jobs added since the job recovery began in earnest in late 2011.

There were some other flukes in the data, too, most notably the 35,000 striking

At least there is modest cohesion in the establishment report data above. The household survey, which is the basis of the unemployment rate, appears to be so messed up that we don't plan on discussing it. Suffice it to say as working-age population growth approached zero, more than 2.5 million workers joined the labor market over the past year, according to this report. And then a half-million of them disappeared in the single, uneventful month of May. Even as job growth collapsed according to the establishment data, the separately calculated unemployment rate fell to the recovery low of 4.7%. We aren't even going to try to make any alibis for the government statisticians.

I suppose the one thing the household survey data may be signaling is that a lack of available workers was a bigger problem than the number of available jobs. We will get a potentially confirming piece of data in next week's Job Openings and Labor Turnover report.

Even with all the flukes and inconsistencies, we would have a hard time saying that "real job growth" was more than 125,000 jobs compared with the previous 12-month average of 220,000 jobs and the consensus expectations of 155,000 workers. Even our year-over-year data shows some modest deterioration from a weather-aided, 2.1% growth rate last winter to 1.9% currently. Still, it hardly looks like a reason for panic.

Stable Hours and Increasing Wages Soften the Blow Hourly wage growth was again strong--up another nickel following a $0.09 gain in April. Wages have grown in 10 of the past 12 months and are now up 2.5% from a year ago (2.4% on an averaged basis).

While we mentioned deterioration in the employment growth rate (from a high of 2.4% to 2.1%), higher wages (from a low of 2.2% to 2.4%) are just about offsetting that. Hours worked, another measure of the health of the employment market, is down infinitesimally from a year ago and flat for most of 2016. Total private wages calculated in this manner have fallen from a 4.9% to a 4.3% growth rate, hardly a reason for panic. With exceptionally weak numbers in June 2015 for both wages and hours, and the guaranteed bounceback in Verizon workers this June, we suspect the June numbers in aggregate will improve.

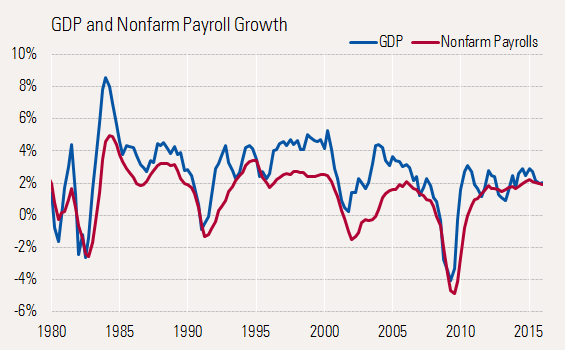

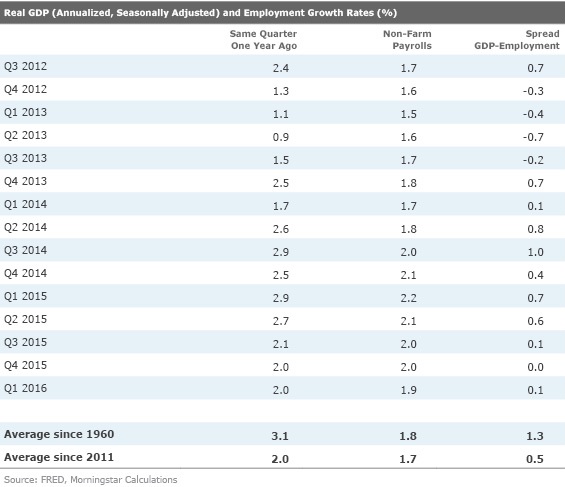

Slowing GDP Growth Signaled Slowing Employment Growth Was in the Works GDP growth and employment growth generally move in tandem. Usually GDP grows faster than employment when the economy is not in recession. Productivity gains usually give GDP an added boost. The graph below shows just how close this relationship has been over an extended period of time, with perhaps a few issues around recessions and early in a recovery.

Since the 1960s, the median spread between GDP and employment growth has been just under 1.2%. In this recovery the spread has been more like 0.3%. However, now even that small spread has all but disappeared. GDP growth for full-year 2015 and 2014 was about 2.4%. However, for several quarters in a row, the year-over-year GDP growth rate has slowed to less than 2%.

Even if the U.S. economy grows at 3% in the second quarter on a sequential growth rate basis (which is just about the highest estimate we have seen), the year-over-year second-quarter growth rate would be just 1.8%. If the average spread were to hold at 0.3%, employment growth would need to fall back to 1.5% or less, which amounts to an average monthly job growth rate of 175,000 workers. Before the dismal May report, the U.S. economy had been averaging 220,000, clearly too high for the slowing GDP growth rate.

Our 2.0%-2.5% 2016 GDP Growth Estimate Is Trending Toward the Low End of the Range We still believe that a 2.0%-2.5% growth rate for 2016, and over the intermediate term, remains reasonable to perhaps just a tad optimistic. At this point, anything much above 2.0% seems like a stretch given the dynamics of recent quarterly results and how the quarterly estimates fall together. Even assuming a strong 3% (and perhaps overly optimistic) sequential growth rate, it will still be very hard to get to 2% GDP growth for the full year or even fourth quarter to fourth quarter.

With a slowing in the key auto sector, little hope for export growth, and businesses that have little appetite for expansion, it's increasingly difficult to see much hope for anything better.

One of the few hopes here is that the weakening employment data keeps the Fed from raising rates, which is likely to keep the housing rally alive. Just a week ago we were worried the Fed would be raising rates, potentially cutting the housing rally short. That now doesn't appear to be the most likely case. In addition, with consumer income growth still healthy and savings high, it just doesn't feel like the economy is about to crumble. Still, growth is slowing and investors and economies dependent on the U.S. will have to adjust accordingly.

Auto Sales Run Out of Gas Perhaps we cried wolf to soon and too often, but it does appear the auto sector is slowing. Even with more incentives and attractive lease programs, auto sales grew a disappointing 1.5% year over year. Year-to-date sales are up 1%, shy of our modest 2% to 3% growth rate for all of 2016.

With the hardest year-over-year comparisons coming later in 2016, our 2%-3% growth forecast is looking a little rich. Losing the growth of this key sector will not be easy to make up in other areas. However, we don't expect sales to collapse, either. And though we have used autos as a key sentiment indicator in the past, we may have to find a new variable to use. We think the auto issue is one of saturation and demographics and not consumer buying attitudes. Plus, slower growth in the auto sector could free up growth for other consumer expenditures.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5SLJLNMQRACFMJWTEWY5NEI4Y.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/05-06-2024/t_bd32499d257a40fe9a757102874ba6c4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)