Why Core Bond Funds Still Make Sense

Even in the face of rising interest rates, bonds remain an important allocation for retired investors.

High-quality bonds are a tough sell these days. Bond yields remain stubbornly low, which means investors are not getting paid much to own them. On top of that, if yields rise, investors may lose money whether they own the bond or a high-quality core bond fund. But many investors--those nearing or in retirement, in particular--can still use the steadiness and diversification benefits offered by a core fixed-income stake in their investment portfolios.

Retired investors have long struggled with how to allocate assets in retirement and how much to withdraw. The "4% Rule" is an oft-used rule of thumb, suggesting that retirees target an annual withdrawal rate of 4% from their retirement assets. Lately, that rule of thumb has been drawing some criticism, though the nuts and bolts of it are still relevant. A number of studies published in the early 1990s determined a "safe" withdrawal rate that, in theory, would preserve portfolio value through retirement while allowing for a reasonable withdrawal rate during retirement. Most of the studies noted the importance of keeping stock allocations fairly high (typically greater than 50%) through much of retirement. One of the most famous of those papers, the Trinity Study, was updated in 2009 and concluded that an allocation of 50% or more to stocks with a 7% withdrawal rate would allow an investor to preserve the portfolio for 25 to 30 years.

Now, some investors may believe that an allocation of "50% or more" to stocks means that a 100% allocation to stocks is appropriate. And for a small handful of less risk-averse investors, or those with other steady sources of income like a pension, perhaps it is. But for those with a shorter time horizon (say, 10-15 years) and with higher risk aversion, an allocation to bonds, and perhaps a hefty one, is a must. Which bond funds should investors turn to? The 2009 Trinity Study used high-grade corporate bonds as a proxy for its bond allocation, though other studies used intermediate-term U.S. government bonds with similar results.

Doubters may point out that U.S. government bonds are generally considered to be the most sensitive to changes in interest rates because they are default-free and therefore don't offer any additional yield cushion to protect against rate swings. The same applies to many investment-grade corporate bonds, which have low default rates and the corresponding low yield premiums. However, long-term investors should not be in the business of changing bond allocations based on predictions of the timing and magnitude of interest-rate movements. What's more, the yield curve tends not to shift in a parallel fashion, making it difficult to predict which bonds will be more or less affected by changing interest rates. For example, the Federal Reserve increased short-term interest rates by 25 basis points in December 2015. By mid-April, short-term Treasury rates rose as expected (the one-month Treasury rate rose to 0.21% from 0.13% the day before the hike was announced), but long-term rates actually dropped (the 30-year rate dropped to 2.58% from 3.00%). A recent Fund Spy from my colleague Eric Jacobson discussed how the yield curve has shifted during previous periods of rising rates.

Generally speaking, most investors should seek traditional bond exposure--a mix of ballast, diversification from equity risk, and income--and should tread lightly in higher-risk bond funds such as those that target high-yield bonds, emerging-markets bonds, and bank loans. Even though predicting interest-rate moves can be challenging, many investors have been drawn to higher-risk bond funds, precisely because they expect them to be relatively insulated from interest-rate swings. That path can be treacherous, however, as these funds will not provide the downside protection that investors need should the equity market take a turn for the worse. For example, during December 2015 and January 2016, the S&P 500 lost 6.5% while the average fund in the high-yield bond Morningstar Category lost 4.0% and the average intermediate-term bond fund was up 0.2%. During the five years through March 2016, the correlation between the average junk-bond fund and the S&P 500 was nearly 0.80 while the correlation with the intermediate-term bond category was 0.20.

Some investors may be drawn to an unconstrained mutual fund that allows a manager take on a negative duration. While this may sound like a good option, most of these funds haven't been tested in a rising interest-rate environment--105 of the 131 funds in the nontraditional bond category launched after 2008. In fact, a number of these funds had negative durations in the third and fourth quarters of 2014 when long-term Treasury rates dropped, causing them to struggle. Performance for the group has been somewhat disappointing, and investors have taken note--the category has seen outflows of nearly $24 billion over the trailing 12 months through March.

In This Case, Boring May Be Best A more plain-vanilla bond allocation--one with a diversified portfolio, minimal credit risk, and moderate interest-rate risk that will act as a true diversifier to equities in a portfolio--is likely the most suitable choice for a retired investor who has a moderate time horizon and is making annual withdrawals from his or her portfolio. These "core bond funds" typically fall into the intermediate-term bond category and generally keep their duration within a stone's throw of the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. Many actively managed core bond funds don't hold the level of Treasuries that the index does, which may help limit some of the negative effects of rising interest rates, though some do hold high-yield bonds, emerging-markets bonds, and the like.

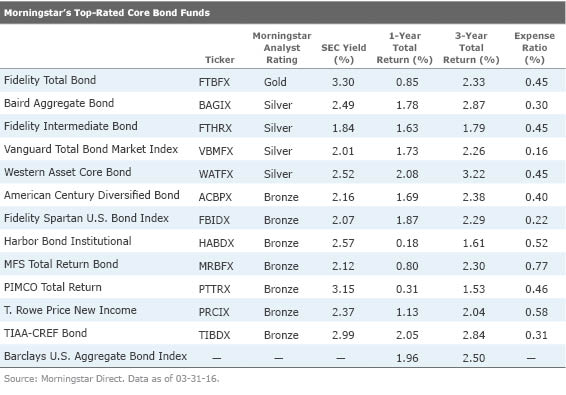

Below, we highlight some of our top-rated core bond funds, which are those that primarily invest in investment-grade corporate bonds, U.S. Treasuries, and agency mortgage bonds, with perhaps small allocations to riskier sectors, including lower-rated and non-U.S. bonds.

Predicting interest-rate movements is folly. Investors, particularly those in retirement, should focus on choosing low-cost bond funds with minimal credit risk that meet their income and time-horizon needs. From that angle, sometimes boring is best.

For a list of the open-end funds we cover, click here. For a list of the closed-end funds we cover, click here. For a list of the exchange-traded funds we cover, click here. For information on the Morningstar Analyst Ratings, click here.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)