The Case for Core Bond Funds

Bonds remain an important allocation for certain investors.

With all the talk of rising interest rates and their potentially negative effects on bond prices and bond mutual funds, some investors may believe they should dump all bond funds from their portfolios. Young investors holding a large allocation to bonds may want to do just that, or at least reduce their allocation. There's little need for the downside protection provided by a traditional bond mutual fund in a portfolio invested for the very long term and a great need for the higher returns generated by equities and the like. Missing out on those higher returns over the long term is a bigger risk than that of the equity market declining in the short term. But for retired investors--especially those taking distributions from their portfolios to fund annual expenses--bonds (and bond mutual funds) still play a crucial role in diversification and downside protection.

Do I Need to Radically Change My Allocation? Retired investors have long struggled with how to allocate assets in retirement and how much to withdraw. The "4% Rule" is an oft-used rule of thumb, suggesting retirees target an annual withdrawal rate of 4% from their retirement assets. Lately that rule has been drawing some criticism, though the nuts and bolts of it are still relevant. A number of studies published in the early 1990s determined a "safe" withdrawal rate that, in theory, would preserve portfolio value through retirement but allow for a reasonable withdraw rate during retirement. Most of the studies noted the importance of keeping stock allocations fairly high (typically greater than 50%) through much of retirement. One of the most famous of those papers, the Trinity study, was updated in 2009 and concluded that an allocation of 50% or more to stocks with a 7% withdraw rate would allow an investor to preserve the portfolio for 25 to 30 years.

Now, some investors may believe that an allocation of 50% or more to stocks means that a 100% allocation to stocks is appropriate. And for a small handful of less risk-averse investors or those with other steady sources of income like a pension, perhaps it is. But for those with a shorter time horizon (say, 10-15 years) and with higher risk aversion, an allocation to bonds, and perhaps a hefty one, is a must. But which bond funds should investors turn to? The 2009 Trinity study used high-grade corporate bonds as a proxy for its bond allocation, though other studies used intermediate-term U.S. government bonds with similar results.

Doubters may point out that rising interest rates have historically had the most negative impact on government and investment-grade bonds, and that investors should consider a different bond fund until rates stabilize. Yes, U.S. government bonds are generally the most sensitive to changes in interest rates because they are, essentially, default free, while the low default risk of investment-grade corporate bonds also makes them quite sensitive to changes in interest rates.

But long-term investors should not be in the business of changing bond allocations based on their predictions of the timing and magnitude of interest-rate movements. In fact, many bond portfolio managers believe it's folly to significantly change a fund's duration based on interest-rate predictions. A great example is 2014, when everyone believed rates were going up, and they dropped. In addition, there are some credible arguments for why gradual, well-expected rate increases may not weigh as heavily on conventional bond funds as much as some doomsayers would believe.

Do I Need to Change Which Funds I'm Using? Understandably, investors may be wondering if they should seek out other types of fixed-income funds to lessen the risks of rising rates. Investors seeking traditional bond exposure--generally a mix of ballast, diversification from equity risk, and income--should avoid higher-risk bond funds, including those that hold big chunks of high-yield bonds, emerging-markets bonds, and bank loans. These funds will not provide the protection investors want from bonds should the equity market unexpectedly take a turn for the worse.

Many investors have turned to bank-loan funds in recent years, with the notion that floating-rate bank-loan coupons will rise with rising interest rates. Bank loans have less interest-rate risk than many types of bonds, but there's still credit risk. Furthermore, bank loans may act more like a short-duration, fixed-coupon bond than a floating-rate security when rates first begin to rise. This is because of Libor floors.

A Libor floor sets a minimum payment amount if the reference rate (here, Libor) falls below the specified "floor." With rates currently below many Libor floors, many bank-loan coupons may not rise with the Fed's first rate hikes. Morningstar strategist John Gabriel discussed Libor floors in May 2015 and noted that at the end of 2014 the weighted average Libor floor on the S&P/LSTA U.S. Leveraged Loan 100 Index was 0.85%. That's 57 basis points higher than June 30's three-month Libor of 0.28%. If, as many expect, the Fed begins its rate hike with a 25-basis-point increase, holders of these loans (and owners of bank-loan funds) will not see any increase in coupons collected. In fact, it would take three 25-basis-point bumps before coupons increased, assuming increases in the federal-funds rate also drive Libor or other reference rates higher. This essentially creates a fixed coupon on a floating-rate security, until Libor exceeds many bank loans' Libor floors.

What about an unconstrained mutual fund that lets a manager go negative on duration? That's got to work, right? Maybe, if the manager is adept at predicting interest-rate movements, but most of these funds haven't experienced a rising interest-rate environment--121 of the 126 funds in the nontraditional bond Morningstar Category launched after 2008. In fact, a number of those funds had negative durations in the third and fourth quarters of 2014 when long-term Treasury rates dropped.

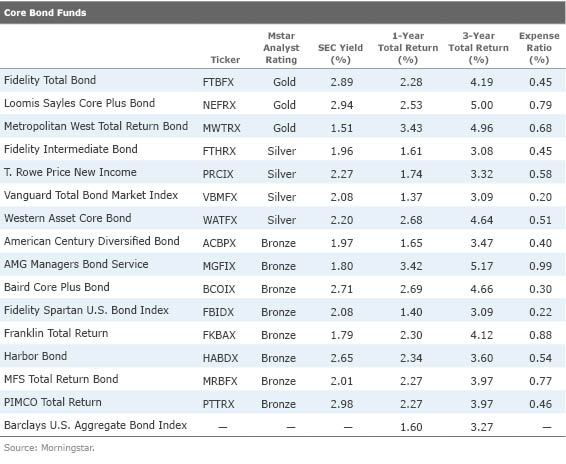

In This Case, Boring May Be Best A more plain-vanilla bond allocation--one with a diversified portfolio, minimal credit risk, and moderate interest-rate risk that will act as a true diversifier to the equities in a portfolio--is likely the most suitable choice for a retired investor who has a moderate time horizon and is making annual withdrawals from his or her portfolio. These core bond funds typically fall into the intermediate-term bond category and generally keep their duration within a stone's throw of the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index. Many actively managed core bond funds don't hold the level of Treasuries that the index does, which may help limit some of the negative effects of rising interest rates, though some do hold high-yield bonds, emerging-markets bonds, and the like.

Below, we highlight some of our top-rated core bond funds, which are those that primarily invest in investment-grade corporate bonds, U.S. Treasuries, and agency mortgage bonds, with perhaps small allocations to riskier sectors including lower-rated and non-U.S. bonds. Predicting interest-rate movements is folly. Investors, particularly those in retirement, should focus on choosing low-cost bond funds with minimal credit risk that meet their income and time horizon needs. From that angle, sometimes boring is best.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)