Fund Costs: The Good and Bad News

The overall trend is great, but 401(k)s remain a problem.

Ripped From the Headlines In Ignites this past month (Ignites being a fund-industry trade publication):

Subadvisors Face Pressure to Shave Management Fees "There's always pressure on subadvisors to reduce their fees," says Tim Clift, chief investment strategist at Chicago-based Envestnet. "We're seeing more subadvisors being replaced by index products."

Competition from exchange-traded and passively managed funds has caused mutual fund expense ratios to fall over the last few years, particularly as active managers struggle with performance, says Clift.

Equity funds, for example, had average total expenses of 74 basis points in 2013 [using an asset-weighted calculation], down from 99 basis points in 2000, according to the Investment Company Institute’s 2014 Fact Book.

iShares Cuts Fees to the 'Core' BlackRock's iShares filed yesterday to drop fees on four exchange-traded funds within its Core series by 2 basis points each.

BlackRock has increased efforts this year to attract buy-and-hold exchange-traded fund (ETF) investors by adding to its low-cost Core series options. The company has not been able to keep pace with Vanguard’s sales momentum, causing its market share to slip. The firm now controls just over 38% of the U.S. ETF market, down from 47% in 2010, according to Morningstar data.

Vanguard Chops Expenses to Match Fidelity Sector ETFs Vanguard has reduced expense ratios for 10 U.S. sector stock exchange-traded funds, plus two other ETFs and more than a dozen mutual funds.

With its reductions, the Vanguard ETFs match the expense ratios of Fidelity’s new suite of 10 sector stock ETFs.

In its announcement of the cuts, Vanguard attributes the lowered costs to its "unique corporate ownership structure" and "relentless pursuit to operate more efficiently and productively."

MFS Slashes Fees on $4.3B Bond Fund, Three Others Four MFS funds will ring in the New Year with lower fees.

MFS reviews its funds’ management fees and expense ratios continuously and compares them with those of competing products in their categories, says James Aber, a spokesman with the firm.

"The changes will benefit the funds’ existing shareholders by lowering expenses while also making the funds more attractive in the marketplace," he says.

Several other firms have cut fixed-income fund fees since late September, including BlackRock, Hartford Funds, Morgan Stanley Investment Management, Prudential, RBC Global Asset Management, and Western Asset Management.

Race to the Bottom The pattern is clear. Across the fund industry, from mutual funds to ETFs, retail shares to institutional, stocks to bonds, fund expense ratios are heading down. Obviously, that is not due to the desire of fund companies to lower their profit margins. They cut because they must. As recently as a decade ago, a fund company could expect its high-expense offering to attract assets with strong performance. No longer. These days, most investors insist upon cheap as a starting point.

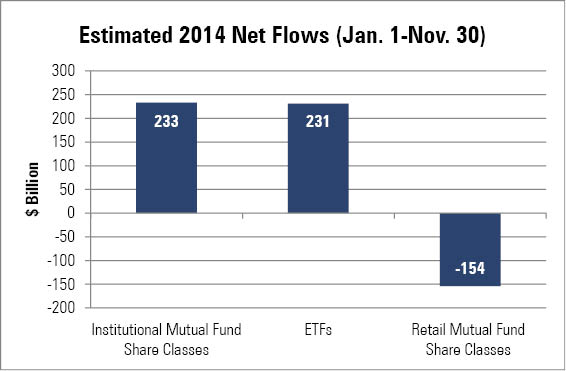

The proof lies in the numbers. As a first approximation of truth, every penny of net new fund sales flows into the two cheapest version of funds, index funds and institutional share classes. Meanwhile, the traditional retail funds that once dominated the industry--meaning both load funds and retail no-load shares--are bleeding assets.

- source: Morningstar Analysts

The marketplace has spoken. In aggregate, fund companies have not delivered enough benefit via above-market returns (or below-market risk) to cover their costs. Recognizing this fact, investors have changed their buying behavior, thereby forcing fund companies to improve their products. And the process is only beginning. Expect many similar headlines during 2015 and for years yet to come.

Snafu And now for the bad news: 401(k) plans.

I’ve often defended 401(k)s, pointing out that critics exaggerate plan costs and conveniently ignore target-date funds, which have revolutionized how employees invest. These days, rather than fuss about investment options and/or chase performance, most 401(k) investors simply plop their monies into a diversified, reasonably low-cost target-date fund and let the markets do the work for them. That makes a lot of sense.

But the rest of the system does not. Because 401(k)s were not created from the top down, with a clear vision of shifting the retirement-savings responsibility from companies (via defined-benefit plans) to employees, they have various accidental drawbacks. One huge problem is that tens of millions of working Americans have no access to such plans.

Another is the mastodon-sized penalty for those who work at small companies. Per a study issued in December by the Investment Company Institute and BrightScope, employees in plans with more than $1 billion in assets paid an average of 33 basis points in annual costs (mostly fund expenses), while those in plans with less than $1 million in assets paid 1.60%.

It would take a powerful love of the status quo to defend the notion that people who work at smaller companies should have dramatically worse retirements than those who work for giant multinational corporations. And the adverb dramatically is no exaggeration--at current Treasury-bond rates, the expense difference of 1.27 percentage points between large and small plans consumes more than half the expected return on a government-bond portfolio.

In addition, there is the litigation. Along with the salutary efforts of companies to negotiate better deals for their employees by demanding cheaper funds, which has benefited the better 401(k) providers and harmed the weaker companies, has come a less-salutary slew of lawsuits. Many giant companies, among them Boeing, Lockheed, International Paper, ABB, Edison International, Caterpillar, Bechtel, General Dynamics, Kraft, and Wal-Mart, have either settled out of court or are in the process of litigation.

These companies had relatively good 401(k) plans. Tens of thousands of 401(k) plans have higher expenses and are less thoroughly monitored than the plans of companies that were sued, and tens of thousands were subject to the same conflicts of interest (which involve various flavors of the employer becoming too comfortable with the plan provider). In short, the lawsuit approach to lowering plan costs is the approach that brings the most benefit to plaintiffs’ attorneys and the least to 401(k) participants.

This is why new 401(k) legislation is required. The marketplace works fine at rewarding excellence and punishing failure when given the opportunity, as with mutual funds. When hampered by a poor structure, as with 401(k) plans, which places unequal burdens on large and small companies (and which also operates behind a series of closed doors), then the courts fill the void. If government is to be involved, better the legislators with a vision of what is to be accomplished than the judges attempting to interpret an accidental series of statutes.

Final Thoughts The United States is extending its investment lead. It already has the world's lowest-cost funds, with the greatest amount of transparency. And it's growing those advantages, as U.S. fund companies feel the pressure to slash their expenses and are encouraged to share more information by advisor demands and by the standards set by ETFs.

However, the overall success is marred by the mess within 401(k)s. The path to better 401(k) results for the average American will not come by extracting punitive payments from the companies that have relatively good plans, nor, in fact, from the legal system at all. It will come from redesigning the industry (some thoughts here) so that the true arbiter of justice, the marketplace of investors, can deliver its verdict.

Late note: Earlier this week, AQR's Cliff Asness addressed the topic that I discussed in my last column ("The Attack on Shareholder Value"). His comments are worth further discussion--but not in today's column.

John Rekenthaler has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)