The Two Great Myths of Social Security Reform

How the debate about Social Security misses the mark.

Note: This column was originally published one year ago, on Feb. 23, 2023. If you missed it the first time around, do give it a read, as it is one of my better efforts. And if not, my apologies for the reprint, but I am currently on vacation. I will publish a fresh article on Tuesday, though.

Misled

The two big myths of Social Security reform are 1) balancing Social Security’s books is necessary; and 2) if attempted, such a task would be difficult.

I realize that this statement seems scarcely credible. Please bear with me.

To address the first issue, Social Security is, to use the parlance, a “pay as you go” system. Mutual funds hold investments. So, too, do pension and endowment funds. The Social Security program does not.

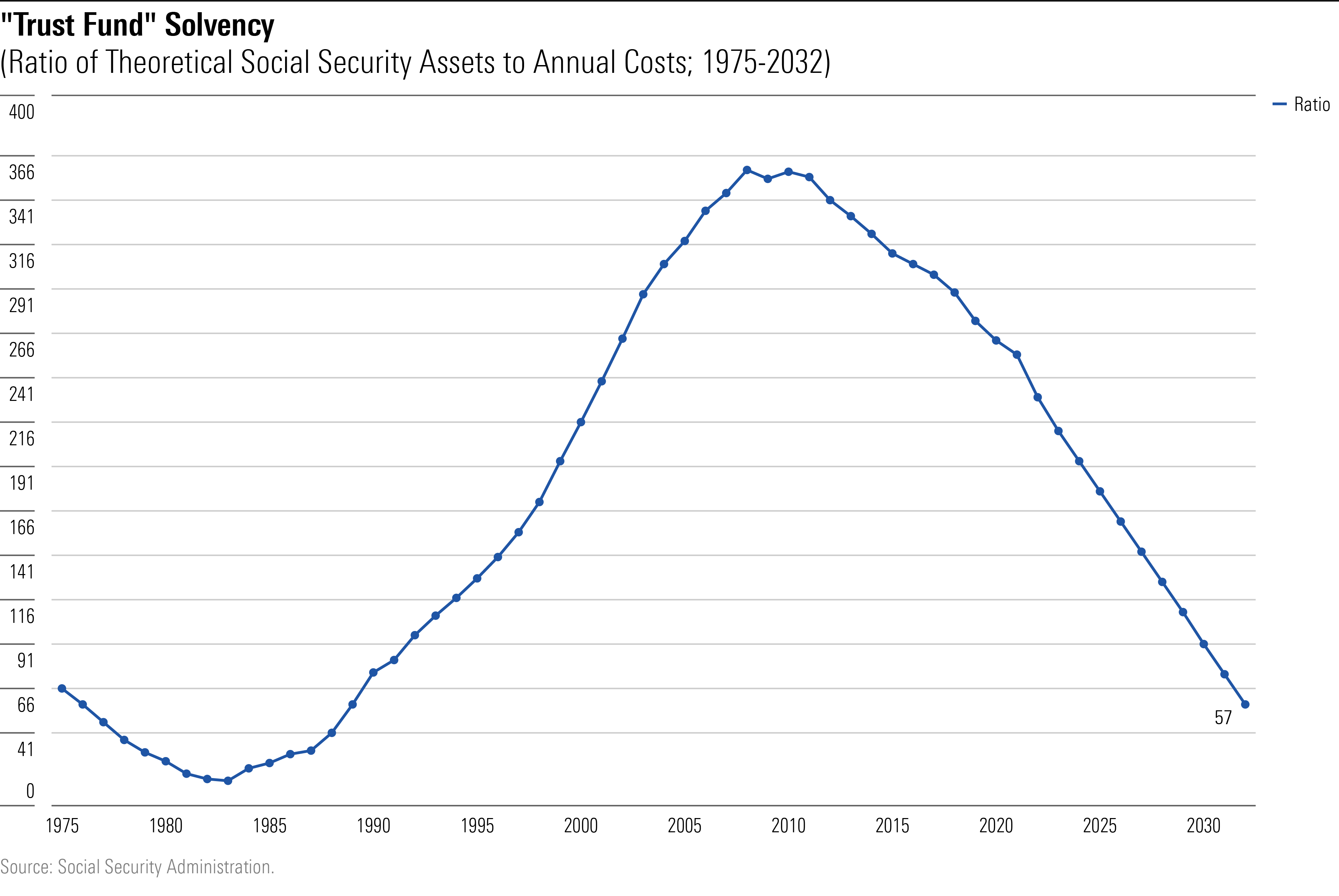

That assertion may confuse you because the Social Security Administration insists otherwise. It purports to run two “trust funds,” one for its retirement payments and the other for reimbursing disability claims. These funds are said to contain the Social Security system’s “accumulated asset reserves.” In truth, however, those “asset reserves” (this column is stuffed with air quotes) are not marketable investments. They are instead Treasury Department IOUs—promises that the federal government will fulfill its future obligations.

Consequently, forecasts of the “Social Security Trust Fund’s” solvency are moot. We might as well monitor the health of Thor, Godzilla, or the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man. No pool of marketable securities increased when Social Security’s tax revenue surpassed its costs, and no pool of marketable securities is shrinking today, when the program’s expenditures exceed its specified income.

In other words, this oft-printed graph, which represents the assets/annual cost ratio of the two “Social Security Trust Funds” (combined to form a single entity), is an accounting creation:

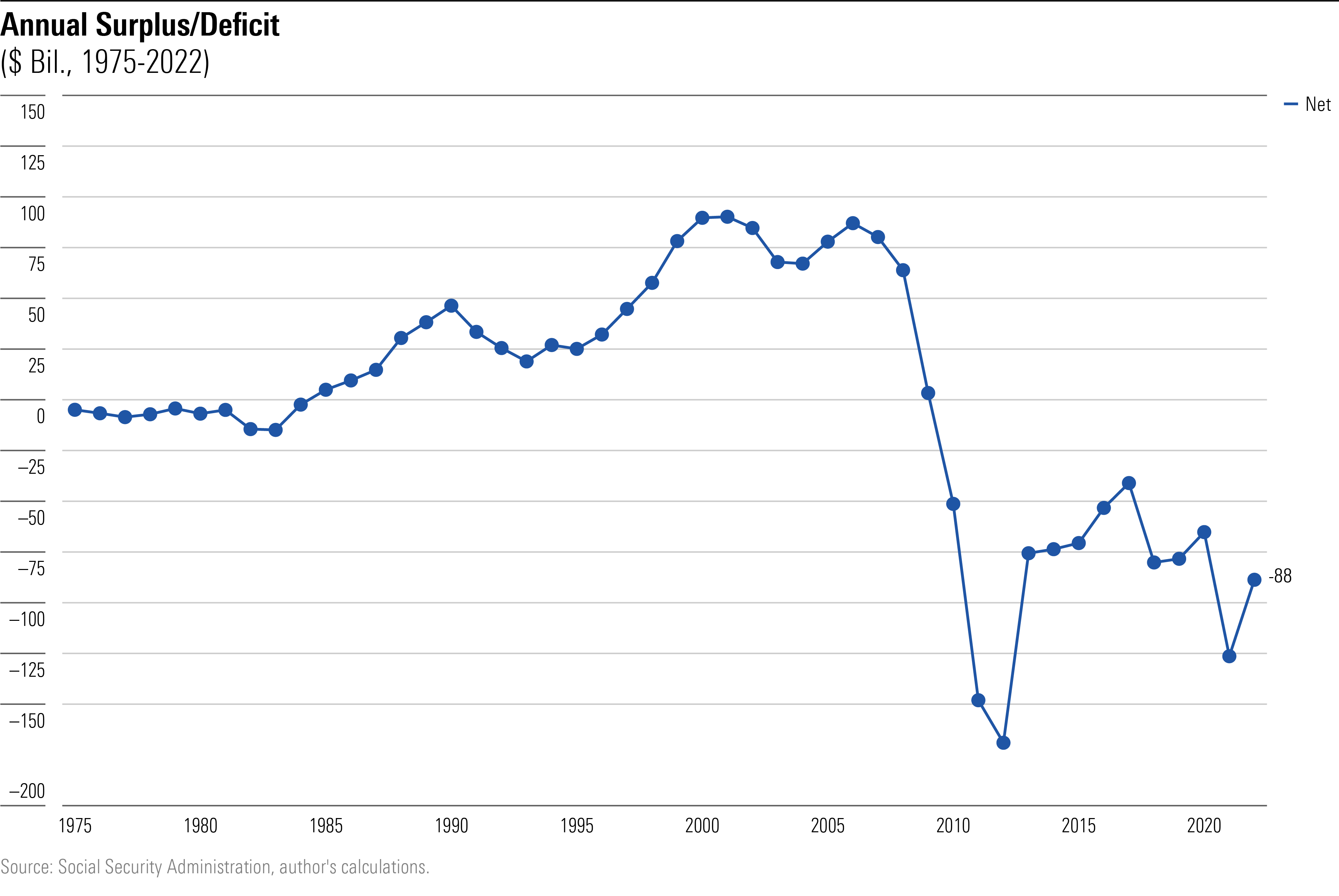

An accurate illustration of Social Security’s finances would not show the rise and fall of a fictional fund but instead the administration’s annual surplus/deficit. That picture looks like this, below.

The Multiverse

Wait now, you might wonder. (I would.) The conventional view of Social Security shows its balance expiring during the mid-2030s, while by my account the system is already bleeding assets. How is that an improvement?

To answer, let’s conduct a thought experiment. Imagine that when the Social Security program was launched, it was financed through general revenue. In that alternative universe, President Franklin Roosevelt created a new payroll tax not to defray Social Security’s costs but instead to expand the U.S. military, in response to Japan’s imperialist ambitions. To convince a skeptical American public that he wouldn’t break the federal budget, Roosevelt pledged to cover all current and future defense spending through his new tax. The military would be self-funding.

The political discussion in that alternative nation would be very different from ours. Social Security’s costs would be taken for granted. The benefit would exist, payments would be made, and the country would quietly pay those bills—as we currently do with military costs. However, the “Defense Budget Trust Fund” would be heavily discussed and criticized, with debates raging about how best to “reform” military spending—as we currently do with the Social Security system.

In short, today’s Social Security discussions are the product of arbitrary decisions that have no effect on the nation’s financial health. Whether the payroll tax is alleged to cover Social Security’s costs or is alleged to cover the military’s costs, matters not. The distinctions are immaterial.

Up for Discussion

This does not mean that Social Security’s finances should be taken for granted. Quite the contrary. The payroll tax is a major method by which the federal government generates revenue, and Social Security benefits are among its two largest costs, along with Medicare/Medicaid. If Congress and the White House decide that reducing the national debt is a task worth pursuing, then the Social Security program is a logical starting point. It deserves hard scrutiny.

But so do other aspects of the federal government’s budget. It little avails the nation’s financial health to “fix” Social Security yet run a ruinous aggregate deficit. (What level of deficit qualifies as “ruinous” is a topic for another time; ask 20 leading economists and you will get 20 different answers.) The problem must be resolved holistically rather than piecemeal.

Let’s consider the subject from another perspective. For a quarter-century, payroll tax receipts eclipsed Social Security payments, meaning that the plan generated a surplus that was used for other purposes. During that time, did anybody say, “The United States should rationalize its infrastructure spending, because not only are highways failing to pay for themselves, but they are also taking from Social Security”? Not to my knowledge. Implicitly, people accept that when running a surplus, Social Security can help to pay for other programs, but when running a deficit, it should not receive similar support.

In short, the Social Security “crisis” is an unhelpful construction. Today’s debate relies upon a financial misperception stemming from historic accident. It distracts us from the matter at hand, which is to determine the appropriate overall level of government spending and revenue, while also helping to advance—or at least not obstruct—the nation’s economic growth. (More than 20 years ago, the director of the Congressional Budget Office advanced this same argument. It continues to hold today.)

Looking Forward

Which brings us to the second myth mentioned at the beginning of this article: that if one were to attempt to balance Social Security’s books, the task would be difficult. Not so. Several reasonable levers exist for matching Social Security’s revenue with its costs. In fact, they could even be used to put the Social Security system in the black. If so, Social Security could once more become part of the federal budget’s solutions, rather than among its problems.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)