Are TIPS a Bargain?

They are, but with an asterisk.

Cheaper by the Moment

Last Friday’s column covered the calamity known as “the 2022 market in Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.” When facing the first serious bout of inflation in its 25-year history, the investment designed to safeguard against inflation promptly surrendered. Intermediate-term TIPS have dropped 12% for the year, with their longer-term cousins down even further.

Then again, from disaster comes opportunity. Perhaps TIPS have fallen far enough to become compelling. This column tackles the topic from two perspectives: 1) as a buy-and-hold investment and 2) as a marketplace security. In the first case, the salient question is, “If I stash away TIPS for 10 years, will I be pleased with my decision?” In the second, the issue is whether TIPS will become cheaper yet. If so, there’s no point in buying TIPS now, since soon they may cost even less.

Buy and Hold

The first angle is easy to address. Unusually, TIPS possess explicit real yields. The underlying mechanics resist simple explanation, because market movements affect the calculations (for example, a security initially issued with a positive real yield can be repriced to have a negative real yield), but suffice it to say, the after-inflation return for TIPS that will be held to maturity is known in advance. (Not precisely because of reinvestment risk, but close enough for a blogger.)

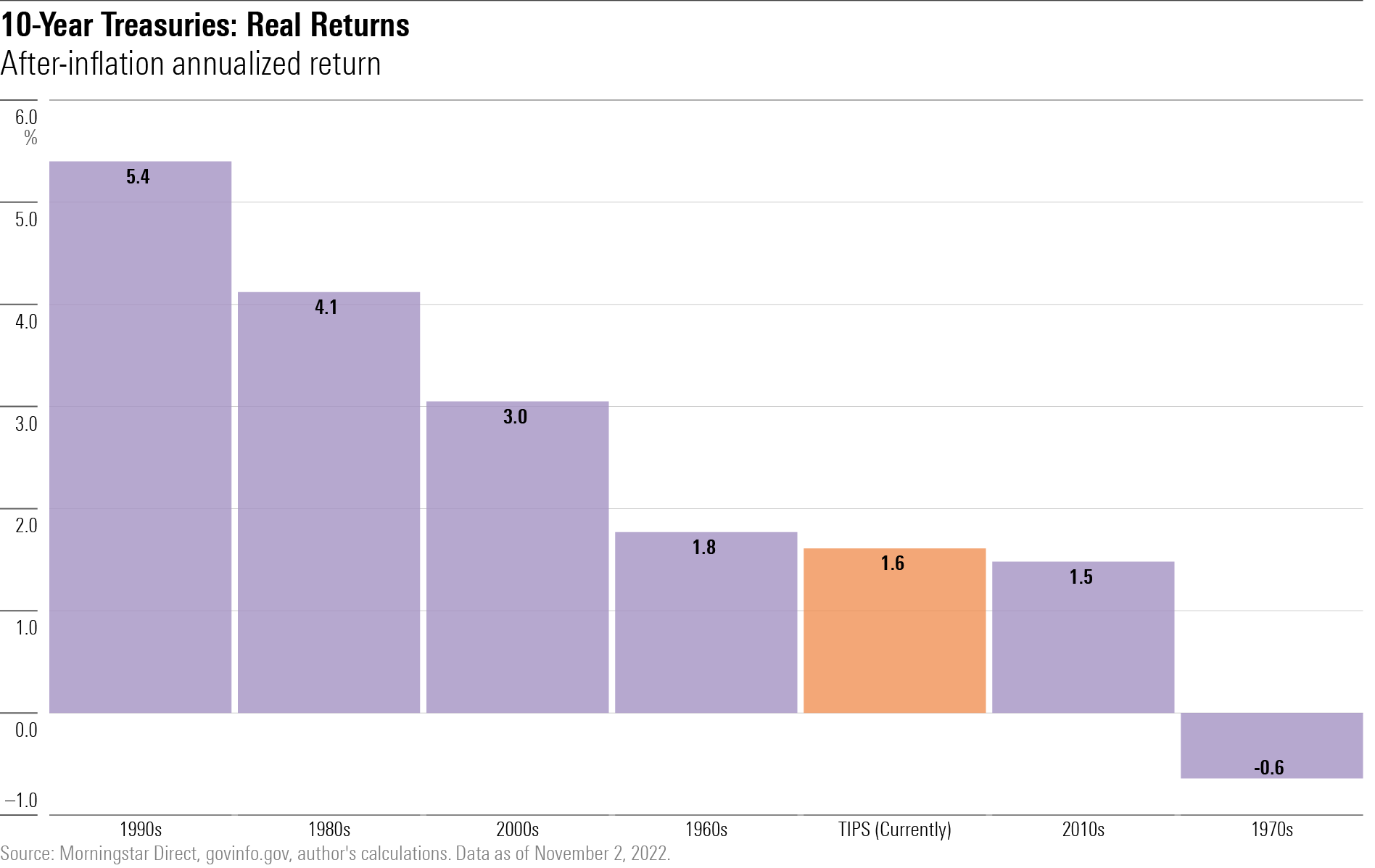

Currently, the amount for a 10-year TIPS is 1.6%. Buy a freshly issued 10-year TIPS, store it in an electronic locker, and a decade from now that security will have returned an annualized 1.6 percentage points above the rate of inflation, as determined by the unadjusted version of the Consumer Price Index. (Again, this account is the abridged version of a longer but substantially similar story.)

We can compare that 1.6% figure against what conventional 10-year Treasuries historically have earned. As 10-year Treasuries debuted in 1953, I started my inquiry in January 1960. From that point onward I calculated each decade’s annualized real return for such securities, assuming they were bought at the start of the decade and held until maturity. Thus, the bar labeled “1960s” represents a 10-year Treasury note purchased in January 1960 and sold in January 1970.

At first glance, TIPS don’t look cheap. In three of the six decades, their natural investment rival, conventional 10-year Treasuries, scored much higher returns than what today’s TIPS will deliver. Twice the results were similar. Only once, during the 1970s, would the real yield on today’s TIPS have outdone what conventional Treasuries ultimately produced.

The next glance is happier. Conventional Treasuries were great during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, but only because their yields exceeded 6.5% at the beginning of each period. That condition no longer exists. Based on current conventional Treasury yields, the 1960s and 2010s are the more relevant comparisons. During those eras, TIPS were fully competitive while also safeguarding against unexpectedly high inflation.

In summary, 10-year TIPS are more appealing than their conventional Treasury competitors. That was not the case a year ago, when their real yields were negative, but the scales have tipped in their favor, no pun intended. (One could also argue for a strategy of combining the two investments, so that the guaranteed portion of an investor’s future returns receives both nominal and inflation-adjusted yields, but that is a subject for another column.)

The Next 12 Months

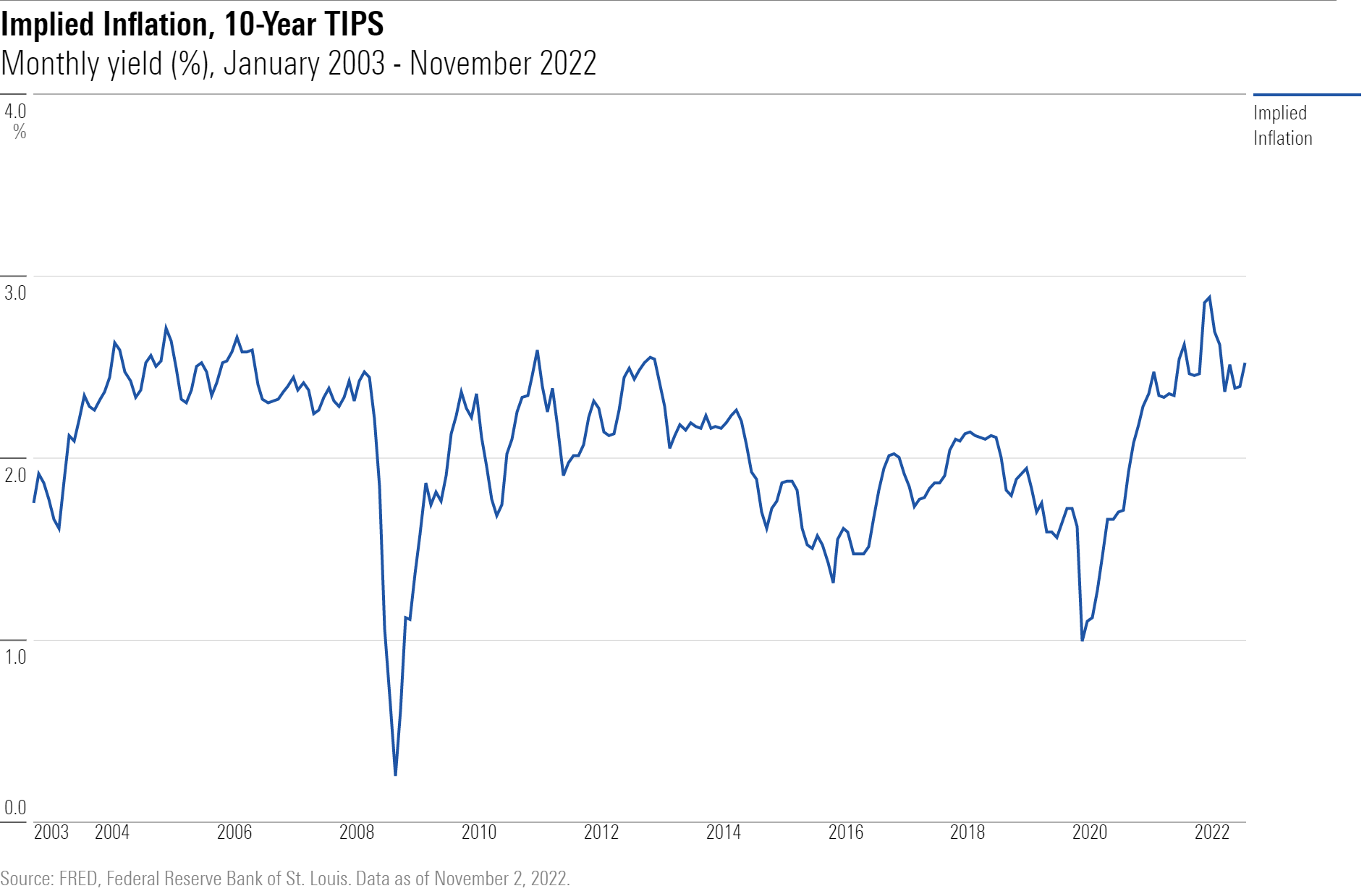

Now onto the consideration of whether TIPS have further to fall. Doing so means thinking about how TIPS are priced. As previously stated, the return on TIPS comes from two sources: 1) inflation and 2) real yield. Although inflation cannot be known ahead of time, we can calculate its expected rate by subtracting the real yield on TIPS from the nominal yield on a conventional Treasury of the same maturity. What remains is the marketplace’s inflation expectation, give or take.

Presumably, that implied-inflation number fluctuates sharply; after all, most people now view inflation as a much larger threat than they did three years ago. However, as the next chart shows, the implied-inflation rate has been relatively steady. It plunged during the two recessionary crises of 2008 and 2020 but otherwise has consistently hovered between 1.5% and 2.5%.

Whereas it’s easy to understand how inflation expectations shift, it’s difficult to envision why TIPS’ real yields move. Why would investors require a 1% real return on a 10-year note guaranteed by the U.S. government—meaning that questions about its credit quality should never affect its price—at one time, but accept far less on another occasion? After all, the pool of investors barely changes from year to year, nor does aggregate investment demand.

This graph is much more volatile than the previous one. From 2003 through 2010, this exhibit (coincidentally) occupies much the same territory as does the implied-inflation chart, fluttering between 1.5% and 2.5%, but during 2010 it drops below 1% and has stayed there until very recently. What’s more, on two occasions the real yield becomes significantly negative.

Overall, real yields on TIPS have been surprisingly unstable, for reasons that experts can explain only after the fact. (Few observers, if any, were warning in 2021 that TIPS might suffer if the Federal Reserve rapidly raised interest rates.) Today’s real yields are high when compared against recent history. That is a positive signal for TIPS, since a decline in real yields would boost their prices. But real yields remain low by pre-2010 standards—and who is to say that yardstick has not become the New Normal?

Summary

Until last week, I had not written about TIPS, partially because I typically discuss equities, but also because I was never tempted to do so. Since this column began, in 2013, the real yield on TIPS had always been below 1%. No longer. Consequently, TIPS have become an attractive buy-and-hold investment. However, as their real yields are as likely to decline as rise, TIPS remain risky for investors who might require liquidity. They would probably be better off sticking with cash.

Correction: This article was corrected to note that the real yield on TIPS since 2013 had not always been negative. It had always been below 1%.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XLSY65MOPVF3FIKU6E2FHF4GXE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)