The Real Problem With Inflation

It erodes not only wealth, but also trust.

The most obvious problem with inflation is that it erodes wealth. I first wrote about this issue way back in May 2020, when inflation had been running at a tepid rate for more than three decades. Since then, inflation has come back with a vengeance: Gas prices are surging, groceries are more expensive, and vehicle prices have spiked. As a result, $100 in 2021 dollars is now only worth about $92 in purchasing power today.

But the more insidious effect of rising inflation is that it fundamentally erodes trust. This is a highly destructive force that spills over into many different areas, as detailed below.

Inflation Destroys Trust in Savings and Investment

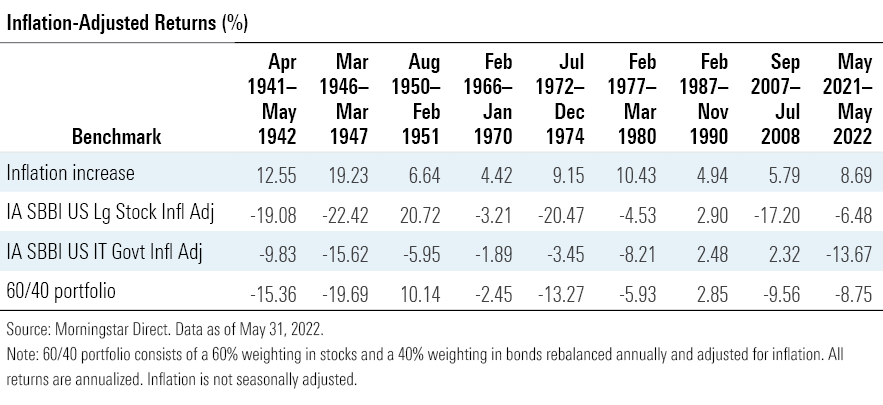

By definition, inflation eats into investment returns, making it more difficult for investors to generate the growth needed to meet their financial goals. As shown in the table below, inflation-adjusted returns on major asset classes are frequently negative during periods of higher inflation. As a result, returns on the classic 60/40 mix of stocks and bonds have often landed in negative territory during inflationary periods.

How Does Inflation Affect Investments? The negative effect of inflation on investment returns adds significant uncertainty to the planning process for individual investors, financial advisors, and institutional investors such as pension plans. If I have no idea how much of a toll inflation might take on my future returns, I have no way of estimating how much I might need to set aside to fund future goals.

Inflation Hampers Workers' Ability to Plan for Retirement

This is closely related to the previous point. During periods of high inflation, investors may need to set aside a larger percentage of income for retirement savings. At the same time, the rising cost of living can increase the risk of prematurely depleting a retirement nest egg. And as John Rekenthaler has pointed out, higher inflation that takes place during the first five years of retirement can be particularly damaging because it permanently increases the total value of portfolio withdrawals.

Retirees who mainly rely on Social Security checks for their retirement income don't need to worry too much about inflation, since Social Security benefits include an annual cost-of-living adjustment that adjusts payments for inflation. But even retirees who mostly depend on Social Security may have to spend down other assets to pay for other major expenses, such as long-term care.

How does inflation affect retirement withdrawals? In addition, many retirees rely on portfolio withdrawals to fund a larger percentage of their retirement spending. As we've discussed in the past, inflation is a major swing factor that can affect how much retirees can safely withdraw from their portfolios each year. The classic 4% rule of thumb for retirement withdrawals assumes that retirees adjust each year's withdrawal amount for inflation, but an above-average inflation rate may make that strategy untenable.

Inflation Impedes Consumers' Ability to Make Rational Purchase Decisions

If I'm making a major purchase, I need to know how much money I have available to spend, how much the item will cost, and how much value it will create relative to other things I could spend money on. Inflation complicates all three of those things. It can also lead to problematic consumer behavior, such as hoarding. If I'm worried that the cost of toilet paper or nutrition bars is only going to trend higher, I might be tempted to load up the cart on my next trip to Costco. This type of panic buying, in turn, can create shortages or fuel further inflation by artificially boosting short-term demand.

How does inflation affect purchasing power and consumer behavior? Inflation can also complicate the decision-making process for bigger-ticket items. For example, if I've been thinking about replacing my car in the next few years, should I buy now to avoid the risk that prices will be a lot higher 12 months from now? Or take the opposite tack and hold off in the hope that price levels will stabilize? Or maybe with gas prices so high, I don't even need a car at all. This type of uncertainty not only creates stress for individuals trying to figure out how to spend their money but can lead to unintended consequences by increasing the level of friction in purchase decisions.

Inflation Rewards Debt Financing

The basic math of inflation means that when inflation is rising, a currency's future value is declining. That makes it more attractive for borrowers to pay back debt with money that's becoming worth less and less. This can be beneficial both for households that carry fixed-rate debt such as mortgages and corporations with leveraged balance sheets (not to mention governments faced with ballooning deficits).

Over time, however, higher inflation can hurt borrowers because it's usually followed by higher interest rates, which increase the debt burden for anyone financing new loans or holding variable-rate debt. This can also create friction issues similar to the one I discussed above; the prospect of higher interest rates and uncertainty about future property values can cause buyers to make poor decisions if they rush into buying a house earlier than they otherwise might.

Inflation Erodes Trust in Government Policymakers

Hindsight may be 20/20, but government officials' handling of the inflation debacle doesn't inspire confidence. As has been widely publicized, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently admitted that she was wrong when she commented in 2021 that inflation represented only a small risk.

Yellen wasn't alone, though. Part of the blame has to go to Congress, which rushed to pass trillions in pandemic stimulus spending after President Joe Biden argued that the main risk wasn't too much spending, but not enough. A minority of economic observers—including former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers—later warned that this helicopter money would inevitably lead to higher inflation.

The Federal Reserve must now engage in a delicate balancing act to try to cool off economic growth without sending the economy spiraling into recession. To do so, it plans to continue hiking up interest rates by at least half a percentage point at its next two meetings. At the same time, the Fed plans to gradually shrink its balance sheet by letting some of its previous asset purchases wind down as principal payments come due.

President Biden, for his part, has also proposed various measures to tamp down inflation, including lowering energy costs; upgrading infrastructure; reducing costs on healthcare, housing, and food; and reducing the deficit by increasing taxes on wealthy individuals and corporations. It's not clear if any of these tactics will work: A recent Ipsos poll found that about 72% of Americans disapprove of how Biden has handled inflation so far.

Glimmers of Hope

Granted, there might be some positive signs that inflation could be easing up. The monthly Consumer Price Index rose by a significantly smaller rate in April, although it ticked up again with the most recent May report. Recent data from the Labor Department suggests the pace of both job growth and wage growth has been moderating. And as Bloomberg recently reported, prices on some of the underlying components used to produce food, electronics, and transportation—namely fertilizer, some types of semiconductor chips, and shipping containers—have recently eased off their previous highs.

Expectations for future inflation over the next 10 years have also fallen. Based on spreads between nominal Treasury yields and those on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities with the same maturity date, the market was pricing in a 10-year breakeven inflation rate of 2.76% as of June 6. That's actually a bit below the 3.20% long-term average since 1913.

Conclusion

At this point, investors can only hope that inflation returns to more normal levels relatively soon. In the meantime, it will continue to have far-reaching effects for both consumers and investors.

Correction: The table has been updated to correct and update data for the most recent period (June 15, 2022).

Correction: This article was corrected to change the timeline for future inflation expecations to 10 years from five years (June 16, 2022).

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XF7WENSYN5BFBFLPPFH7BJYUHE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)