The Largest Funds are the Safest Bets

The odds favor Goliath.

Bigger is Better?

Small funds are alluring. They invest where the giants cannot, pursuing less-liquid opportunities and/or trading rapidly. In addition, because they operate quietly, their strategies stand a better chance of remaining undiscovered. For that reason, institutional buyers seek "emerging managers"; Morningstar researchers worry about popular funds outgrowing their usefulness; and fund companies sometimes close their doors to new investors. The best gains come secretly.

There are, however, advantages to greater size. Their obvious one is economy of scale, which permits bigger funds to charge lower expenses. For shareholders, a penny saved is truly a penny earned. Less noticeably, the behemoths offer two further benefits. First, because they operate profitably, they are likelier to survive. Second, asset growth sends a positive signal. To attract their many investors, these funds did something right. Perhaps those attributes will endure.

By the Numbers

To test the thesis, I sorted all U.S. mutual funds that existed in May 2001 into six asset classes: 1) allocation, 2) domestic stocks, 3) international stocks, 4) municipal bonds, 5) specialty equity, and 6) taxable bonds. I then measured how the largest 20 funds for each of those six groups performed, comparing the results for those 120 funds to the rest of the industry. On average, did the bigger funds triumph, or were they surpassed by their smaller rivals?

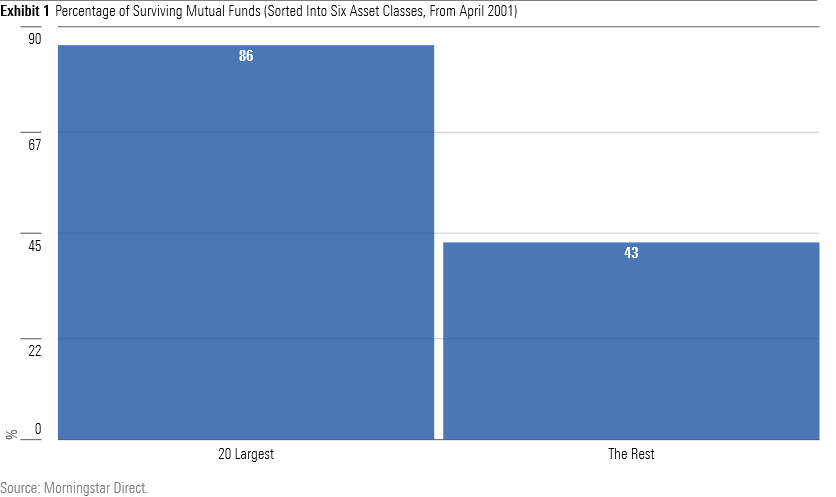

One thing is for certain: The whales are far more persistent.

After two decades, only 43% of everyday funds survived. The rest were either merged into other funds, typically (but not always) from the same fund family, or they were liquidated. Either way, shareholders received something different than what they had originally purchased. In contrast, 86% of the largest 20 funds remain in existence. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the big funds performed well, but they did achieve the minimum, by living. The other funds, not so much.

Higher Returns

Next, I assessed the surviving funds’ 20-year returns. This test wasn’t fair to the largest funds, which had buried relatively few of their weaker members, but the alternative was to compute a customized return for each expired fund, based on the date of its disappearance. That prospect struck me as distinctly unappealing. (When generating data, discretion can sometimes be the better part of valor.) So, I kept the measurement simple, with the excuses to follow.

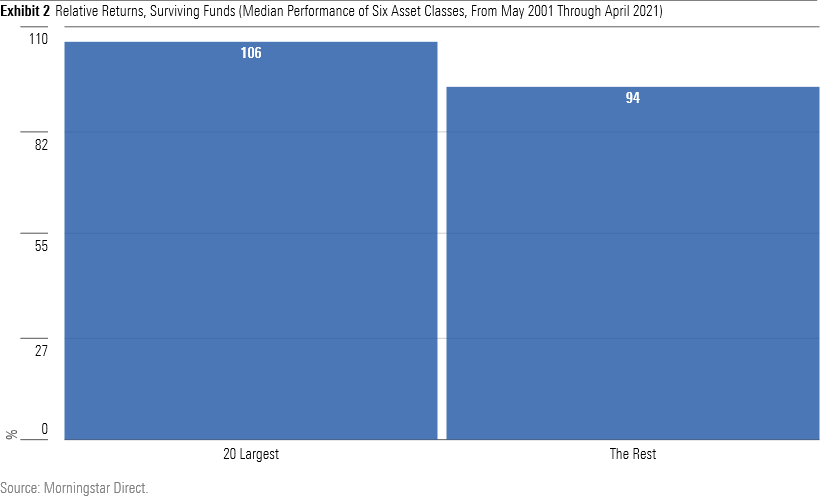

I need not have bothered. Even while handicapped by the methodology, the bigger funds enjoyed comfortably higher returns than did the rest of the industry. Exhibit 2 below depicts median relative returns from May 2001 through April 2021 for: 1) the 20 largest funds, and 2) the rest of the industry’s funds. The relative returns are calculated against each fund’s benchmark; a normal score is roughly 100. (For technical reasons, the overall average is not exactly 100.)

A comfortable victory for the larger funds. Their median results were 6% above the Morningstar Category averages, while those of their smaller rivals were 6% below. The larger funds led in five of the six asset classes, trailing only with taxable bonds. They were also less volatile among the equity categories, although not so with the allocation and fixed-income funds.

The larger funds' achievement owes to two factors. One is lower costs. In 2001, the 20 largest municipal-bond funds possessed an average expense ratio of 0.53%, while all other muni funds averaged 0.80%. That 27 basis points of cost difference accounts for more than half of the larger muni funds' performance advantage. The other is organizational quality. Most of 2001's largest funds were sponsored by fund companies that earn high Morningstar Stewardship Grades.

A third possibility, suggested by some co-workers upon hearing of these findings, was that the bigger funds have ridden a tailwind, because their size forces them to hold larger-company stocks, which have thrived. In other words, the big funds have been lucky. Not so. While it’s true that blue chips have led secondary stocks in recent years, over the full 20-year period the Vanguard Small Cap Index NAESX has comfortably beaten the firm’s 500 Index VFIAX. Being big should not have been helpful.

Fewer Duds

Larger funds scored few spectacular successes. Even if big funds could invest aggressively, few fund-company CEOs would permit such decision. A $50 billion fund with a 0.50% expense ratio represents a $250 million annual check. Increasing that shareholder base so that it generates even more revenue is great--but not if it comes with significant risk. Cash cows demand reverence.

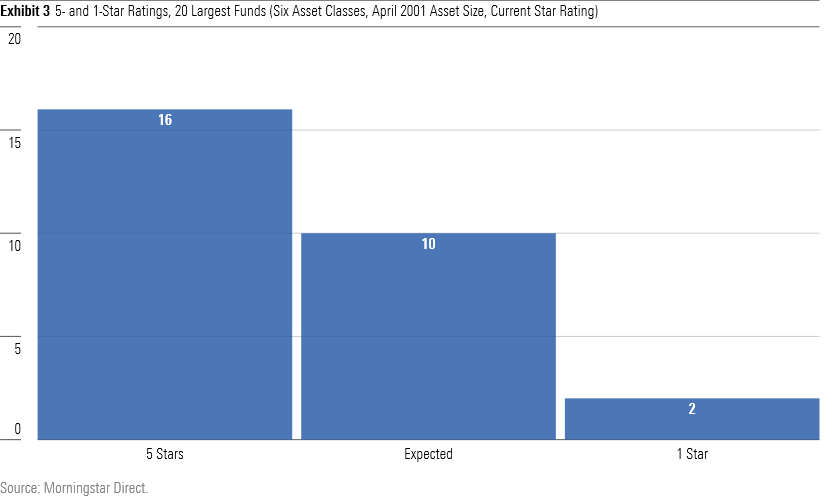

Then again, there’s much investment merit in avoiding disasters. As shown by Exhibit 3, larger funds rarely flop. Not only have most of 2001’s leaders remained alive, but few have strongly disappointed. Among the 103 of the 120 largest funds from 2001 that still exist, only two currently carry Morningstar’s lowest rating of 1 star. In contrast, a randomly selected collection of 103 funds would be expected to have 10 such funds, as 1-star funds compose 10% of the distribution.

There are also more top-rated funds, which also have a 10% distribution, than chance would dictate. While that outcome is to the larger funds’ credit, most of their 5-star designations come from combining solid returns with low risk, rather than gaining spectacularly. While smaller funds tend to be less successful than their bigger rivals, they do contain the future superstars. (Of course, to profit from this knowledge, buyers must be able to identify these winners in advance.)

ETFs, Too

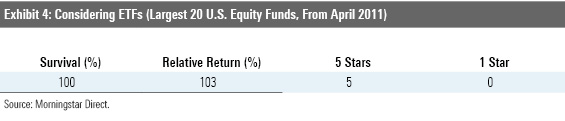

Thus far, I have spoken only about mutual funds. But the same lessons apply to exchange-traded funds, or ETFs. There were too few ETFs in 2001 to justify a study, but bumping the starting point to 2011 yields the same conclusion. Among the domestic stock funds that dominate the industry, every one of the 20 largest ETFs from May 2011 has survived, with a median relative return score of 103. Five have since earned Morningstar’s top star rating, while none are rated at 1 star.

Neither the ETF results, nor those for mutual funds, are so overwhelming as to suggest that fund investors should screen by asset size. This evidence does not more than shade the odds. However, it should allay the common concern that winning funds might struggle to digest their newfound success. Becoming popular has not damaged the prospects of the industry’s largest funds. Quite the contrary.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)