What's Behind the Strong Performance of Big Funds?

Low fees give the largest active funds a big boost.

A version of this article first appeared in the September 2020 issue of Morningstar FundInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of FundInvestor by visiting the website.

Today, the biggest bond fund is a huge success. Pimco Income PONAX under Dan Ivascyn produced top 2% returns in its Morningstar Category over the 10 years ended in July 2020. Yet the largest actively managed equity fund, American Funds Growth Fund of America AGTHX, is slightly behind the median large-growth fund over the trailing three-, five-, and 10-year periods.

It has long seemed to me that big actively managed bond funds are better bets than big actively managed stock funds. (For passive, size only matters if it brings down fees, so I'll leave them out of the discussion.) But I've never really looked that closely at the comparison.

I pulled all actively managed funds with more than $20 billion in assets under management to see if the data supported my view. The average percentile rank for big stock funds was 38 for three years, 33 for five years, and 29 for 10 years. That's quite good.

Of the 41 equity funds, 10 produced top-decile returns. Funds like T. Rowe Price New Horizons PRNHX, Fidelity Growth Company FDGRX, and Vanguard International Growth VWIGX were brilliant. In fact, all 10 were well-suited to the current market, which has been dominated by giant tech stocks. None of the funds landed in the bottom quartile, and the worst came from Oakmark International OAKIX, whose smaller-value tilt put the fund in the bottom 30%.

As good as the stock funds were, the bond funds were better. On average, they produced percentile ranks of 31, 28, and 21 over the trailing periods. That's really good. Led by Pimco Income and Baird Aggregate Bond BAGIX, four of the 20 giant bond funds produced top-decile returns. Only one fund, Vanguard Intermediate-Term Investment Grade VFICX, had below-average returns.

Why might large funds do so well? For one thing, investing is a very scalable business. Another 20% in assets doesn't require a 20% increase in staff and other costs. A large fund company can attract talent and hire more researchers and still have plenty left over to cut fees and of course boost its own profits. Over time, the firm and its funds build a competitive advantage of good managers, analysts, quantitative analysts, programmers, and more.

On the downside, asset growth can narrow a manager's investment universe, as less-liquid securities are out of reach. But for funds invested in investment-grade bonds and large-cap equities, those limitations are mild. Still, asset growth is a greater problem for equity funds, and that may account for the slightly weaker performance.

But the performance figures above aren't enough to make the case for big funds in either asset class. When you look at returns and current assets, you are blending cause and effect. Funds with poor performance will get outflows and have little appreciation, thus leading some of them below the $20 billion threshold. Meanwhile, great performers will see their assets surge.

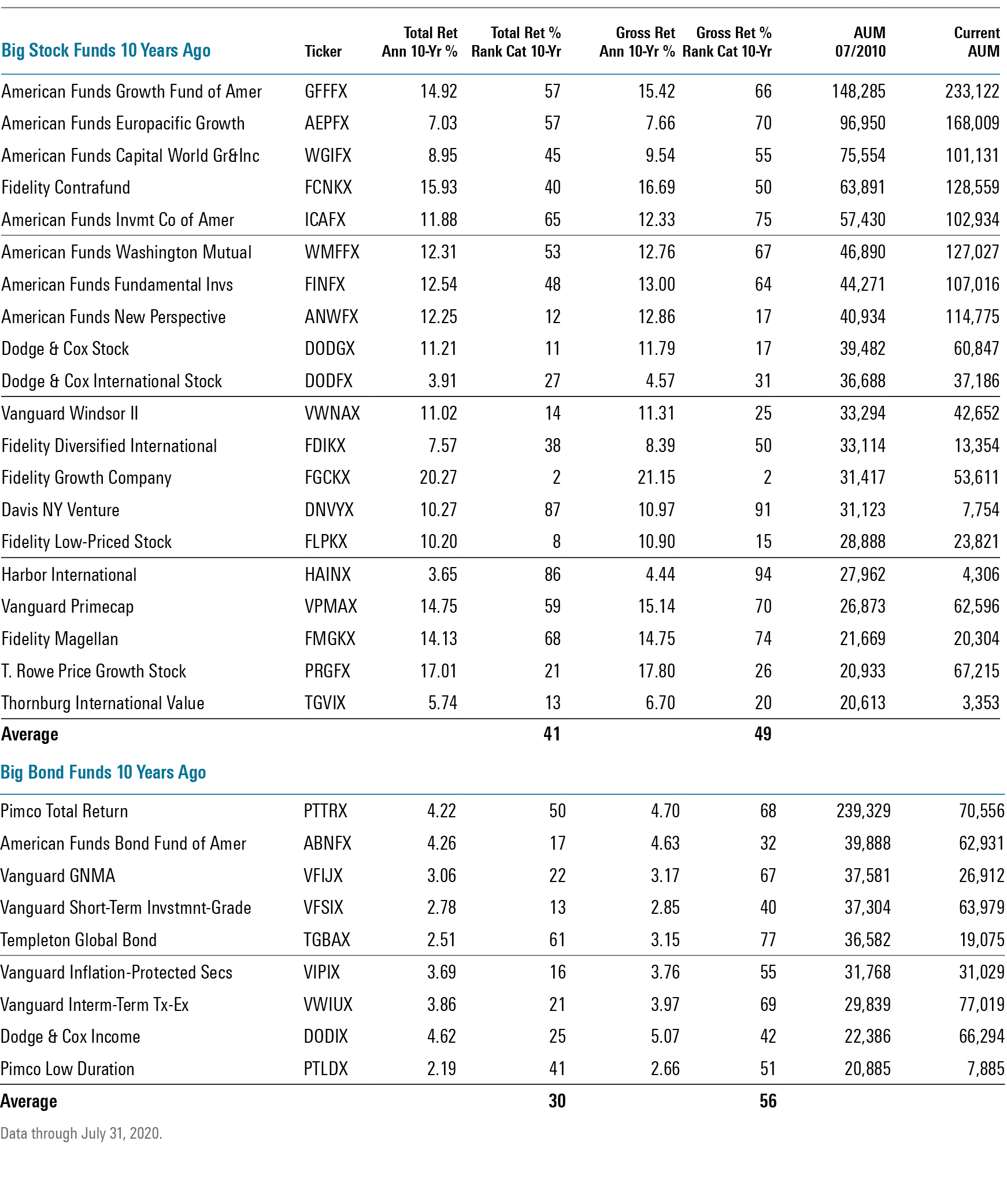

So, the next step is to run the screen for any fund with assets greater than $20 billion 10 years ago. Then, I looked at returns over the ensuing 10 years. I chose the institutional share class when available to make sure I wasn't helping one asset class over the other by using a cheaper share class.

Now results are less impressive.

For giant equity funds, returns for 10 years were top 41% compared with top 29% in my original test. That's decent but less compelling. Sure enough, two funds with returns in the bottom quintile, Davis New York Venture NYVTX and Harbor International HAINX, fell below $10 billion in assets and thus were not included in my first set of figures. And both funds' value tilts hurt returns relative to their blend peer groups.

Perhaps more telling is Fidelity Magellan FMAGX, a fund that finished in the bottom third over 10 years. The fund had long been the biggest and apparently the best. Peter Lynch and his successors initially produced strong returns, then solid returns, then lousy returns. The fund's asset base proved to be quite a burden for Lynch's successors, and it served as a warning about funds getting too large. Ten years ago, its asset base had shrunk to $21 billion, and today it's $20 billion as investors continue to head for the exits. Asset size really hasn't been its primary issue for the past 15 years or so. Rather, the fund just had managers who didn't have enough skill and luck.

As for bond funds, they beat their stock brethren once more. They finished the ensuing 10 years in the top 30% on average. Middling performer Pimco Low Duration PTLDX was the only one no longer above $20 billion when the 10 years ended.

Was it low fees that produced those pleasing returns, or was it something more? To answer that, we need to look at gross return percentile ranks. Gross returns add the fund's expense ratio back to returns so that you can assess the portfolio's returns before fees. If it is something more than low costs, gross returns should still be good.

For equities, the percentile rank of gross returns was 49 on average. To put it another way, only low costs lifted equity funds above average. For example, Fidelity Diversified International FDIVX slipped to 50 from 38 and American Funds Capital World Growth and Income CWGIX dropped to 55 from 45. Some funds were still in the top quartile, though. Fidelity Growth Company FDGRX was in the top 2% on both counts. Fidelity Low-Priced Stock FLPSX slipped to top 15% from top 8%, and Dodge & Cox Stock DODGX dropped to a still solid 17% from top 11%.

Meanwhile in fixed income, the drop was even greater. That top 30% ranking fell to the 56th percentile on a gross-return basis. So, bond funds had a greater fee advantage than equity funds, but that was all they had. To be fair, a number of the big bond funds are Vanguard funds that are run as near index funds. Some are in areas that were little indexed when launched, and their idea is to be very close to the index because low fees allow them to consistently outperform most peers and have a healthy yield without added risk. To put it another way, that middling gross return is really by design, just as it is for index funds.

The Vanguard funds had an excuse, but the big funds not named Vanguard did not do better on gross returns. Their average gross returns landed in the 54th percentile.

So, in short, we see that after fees, big bond funds did quite well. But there was nothing magical about size. That tells me you should continue to make fees a big part of your fund selection, but there's no need to seek out large funds. A smaller fund with an equally cheap expense ratio figures to do just as well as a larger fund after all.

It does suggest something for fund companies, though. It tells me that they haven't shared enough economies of scale with investors. Getting larger allows a fund's fees to come down, but it looks like they only come down as much as the alpha advantage given up.

Source: Morningstar.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/fcc1768d-a037-447d-8b7d-b44a20e0fcf2.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/fcc1768d-a037-447d-8b7d-b44a20e0fcf2.jpg)