Real Estate Funds, Private REITs, and BREIT: What You Need to Know

The pluses and minuses of an alternative to real estate mutual funds.

Real estate exposure can be an important part of a diversified investment portfolio, and real estate mutual funds are generally the easiest and simplest way to get it. But if you have such funds in your portfolio (as I do in my 401(k)), you’re probably aware that they’ve struggled over the past year. In 2022, the average fund in the real estate Morningstar Category lost 26%, and the MSCI US REIT Index similarly lost 25%.

In this grim environment, private real estate fund Blackstone Real Estate Investment Trust Inc., or BREIT, has attracted both positive and negative attention. BREIT gained 8.4% in the first 11 months of 2022, a period when the real estate category lost 22%. In December, however, BREIT restricted the amount that shareholders could withdraw from the fund, rattling investors and causing parent Blackstone’s stock price to fall. These developments highlight some of the pluses and minuses of BREIT and other private REITs, and the ways they differ from real estate mutual funds.

Mutual Funds Versus Private REITs

The most important difference between a real estate mutual fund like Vanguard Real Estate Index VGSIX and BREIT is in what they can buy. With few exceptions, mutual funds must hold publicly traded securities, which generally means real estate investment trusts. These companies hold portfolios of real estate and get favorable tax treatment if they pay out at least 90% of their income to shareholders as dividends.

BREIT is itself a REIT, albeit not a publicly traded one. It directly owns property, and it can put up to 20% of its assets in real estate fixed-income instruments, including corporate bonds, mortgages, commercial mortgage-backed securities, and collateralized debt obligations. It also pays out most of its income as monthly distributions.

Another key difference is liquidity. An open-end mutual fund is highly liquid, allowing unlimited inflows and outflows. Investors can put in or withdraw as much money as they want at any time. In contrast, BREIT sells and repurchases shares monthly only, and its prospectus cautions that the vehicle is intended for people “who do not need near-term liquidity.” This restriction allows BREIT to hold less-liquid investments, which tend to be riskier but potentially more lucrative.

BREIT shareholders usually can cash out only when the fund repurchases its own shares, but it limits those repurchases to 2% of the fund’s net asset value each month, or 5% each quarter. In December 2022, BREIT announced that because it had repurchased shares representing 4.7% of NAV in October and November, only 0.3% of the fund’s assets would be available to shareholders in December. Beyond that, investors would have to wait another month to get their money.

Restrictions and Risks

Anybody with money can invest in mutual funds, which are intended for retail investors and regulated by the SEC. BREIT and other private REITs do not have to be registered with the SEC, however, because they are intended for more-sophisticated investors, who (in theory) better understand the fund’s risks and are less vulnerable to losses.

Investors in BREIT need to have either a net worth of at least $250,000 (excluding their home, home furnishings, and automobiles), or a gross annual income of at least $70,000 and a net worth of at least $70,000. That’s not as strict as most hedge funds’ criteria, which often require a net worth of $1 million or annual income of at least $200,000, but the rules still substantially limit the number of people who can invest. (Some states have further restrictions, prohibiting investors from putting more than 10% of their liquid net worth in vehicles like BREIT.)

One of the main reasons for such restrictions is because BREIT is allowed to take risks that retail mutual funds typically cannot. BREIT’s prospectus includes an astonishing 90 pages of risk factors, while the largest actively managed real estate mutual fund, Cohen & Steers Real Estate Securities CSEIX, has five. That’s attributable, in part, to the many and often forbiddingly complex real estate debt instruments that BREIT holds, and to the derivatives it uses for hedging and other purposes. A 2022 bet on rising rates using interest-rate derivatives, for instance, turned out very well for BREIT and helped its impressive performance. But investors should remember that derivatives bets that don’t work out can exacerbate losses.

Fees

Most private REITs cost much more than mutual funds. BREIT’s S shares, with a minimum investment of $2,500, cost 2.1% per year (a 1.25% management fee plus a 0.85% stockholder servicing fee), in addition to a front load of up to 3.5%. The I shares, which have a minimum investment of $1 million, charge only the 1.25% management fee. That’s still more expensive than 66 of the 68 institutional share classes of U.S.-sold real estate mutual funds.

On top of those fees, BREIT shareholders must pay 12.5% of any gains beyond 5%, similar to most hedge fund performance fees. The high price tag may seem worth it when the fund performs as well as it did in 2022, but it’s a lot less attractive in the inevitable down times.

Other Private REITs

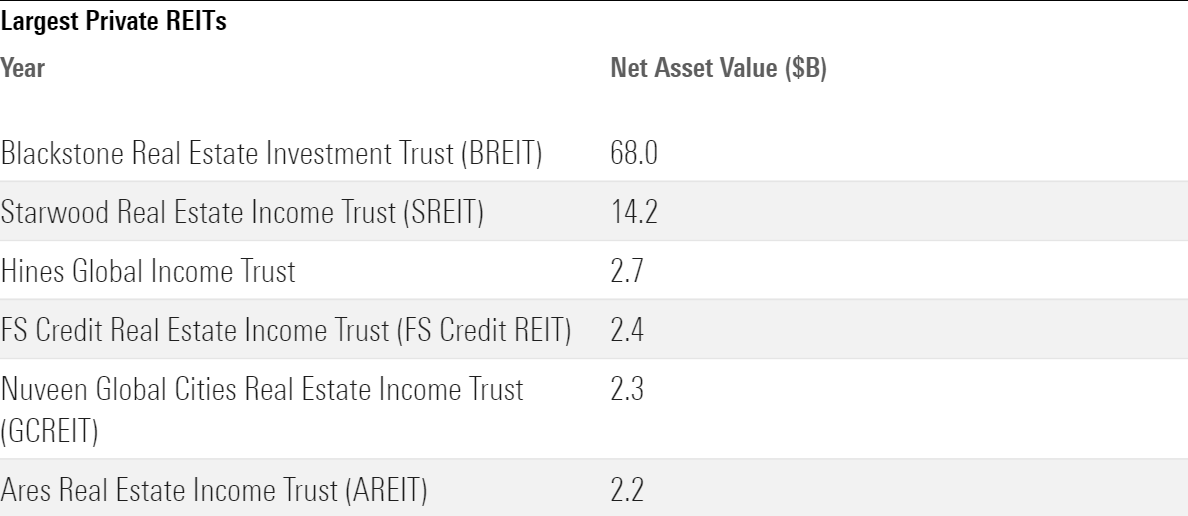

BREIT is by far the largest private REIT, with a net asset value of $68 billion as of Nov. 30, 2022. Its biggest rival is Starwood Real Estate Income Trust, or SREIT, with a net asset value of $14 billion as of Nov. 30, 2022. SREIT has similar monthly liquidity limits, investor financial requirements, and fees. It even outperformed BREIT in the first 11 months of 2022, with a total return of 8.7% versus BREIT’s 8.4%, and it similarly restricted repurchases in December.

As the above table shows, other prominent private REITs are smaller, with net asset values under $3 billion (as of Nov. 30, 2022). As their names imply, these focus on different areas of the real estate market, but they’re all similar in their structure. In general, all private REITs tend to feature the same pluses and minuses as BREIT; retail investors should approach each of them with caution. Real estate mutual funds are sufficient for most investors’ exposure to the sector.

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1ec055c4-13ba-4cb0-bbe5-607ba591d202.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HTLB322SBJCLTLWYSDCTESUQZI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/TAIQTNFTKRDL7JUP4N4CX7SDKI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1ec055c4-13ba-4cb0-bbe5-607ba591d202.jpg)