How Safe Is Gold?

The decision to invest in gold comes down to two factors.

Last month, The Wall Street Journal published an article entitled “When Markets Get Scary, Mom and Pop Buy Gold.” (The Journal’s print version carries the more sober headline of “Individual Investors Seek Safety in Gold.”) Underlying the piece was the news that for the first time 10 years, Gallup poll respondents preferred gold to stocks when asked to name “the best long-term investment.”

As gold has returned less than equities over the past 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 years, counting both domestic and international stock markets, one can interpret that answer as indicating either that the public believes that mainstream investments will soon collapse, or that, though it sacrifices total-return potential, gold offers a level of protection that stocks lack. The Journal’s author favored the latter, which strikes me as the correct choice.

Consequently, the story featured investors praising gold’s dependability. In particular, its lead quote struck me: “Precious metals are kind of what just makes it so I can sleep at night,” stated a middle-aged Massachusetts engineer. “It’s impossible [if owning gold] that I’m going to end up in a bread line somewhere, waiting for someone to drop something in my hand, so I can eat.”

Let’s consider that statement.

1) Short-Term Volatility

Customarily, financial risk is gauged by near-term movements. There is good reason for that practice. Assets that decline by 20% in a week are much likelier to suffer severe future losses than those that never fall by 5%. (Assuming, of course, that Bernie Madoff is not the accountant.) Also, many investments must be judged by what has occurred recently, as they lack long-term histories.

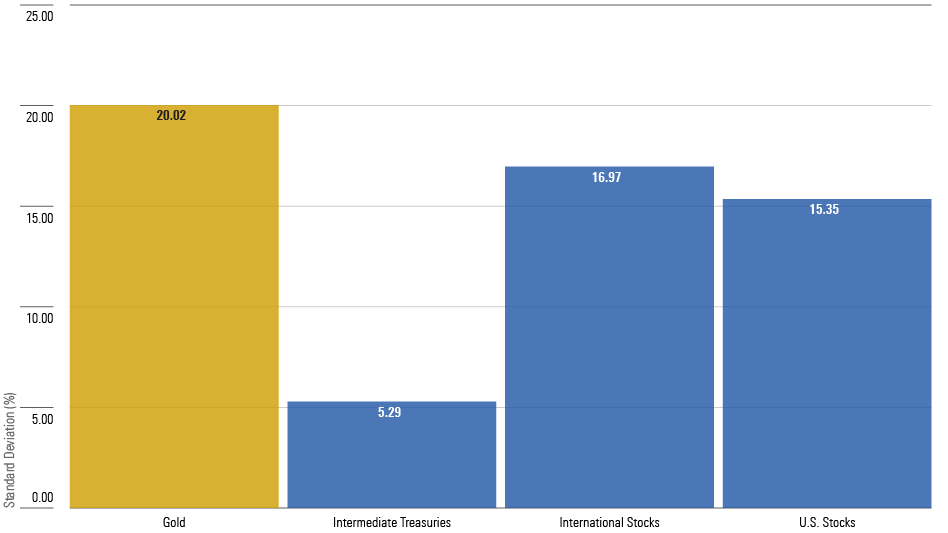

The following chart shows the annualized monthly standard deviations, since September 1971, for four asset classes: 1) gold bullion, 2) intermediate-term United States government notes, 3) international stocks, and 4) U.S. equities. I used that start date because in August 1971, President Nixon announced the “temporary” suspension of the Bretton Woods accord. That interruption soon became permanent, thereby creating a new and still current gold price regime.

Standard Deviation of Monthly Returns

By this statistic, gold has been riskier than equities. The difference isn’t huge—for example, gold has been less volatile than technology-stock indexes—but it nevertheless would seem to refute the engineer’s claim. Conventional analysis indicates that gold bullion is a relatively hazardous holding. (The shares of gold-mining companies are chancier yet.)

But this investigation is insufficient. After all, the engineer did not fuss about monthly swings. What worried him was the possibility of one-way movement, leading to the loss of his capital. Although related, the two items are not identical. It could be that gold prices have fluctuated sharply in the short term but then reversed to the mean. If so, gold would indeed be a safe choice according to his barometer.

2) Long-Term Impairment

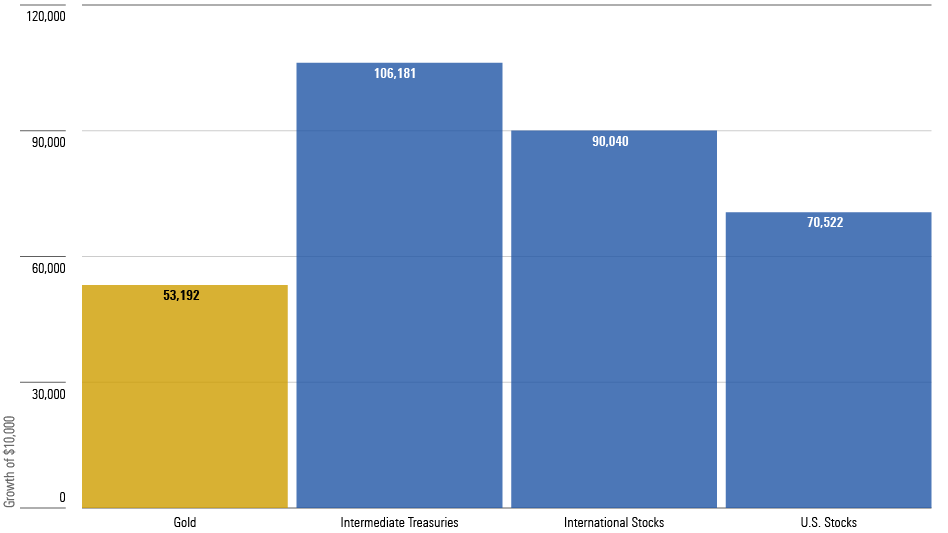

We can test that hypothesis by measuring the lowest long-term performance managed by gold through the study period. On an inflation-adjusted basis—nominal returns are beside the point, as what matters is the preservation of purchasing power—what was the weakest 10-year outcome for a $100,000 investment in gold bullion? For comparison’s sake, I included three other assets: intermediate-term U.S. bonds, foreign equities, and domestic equities.

Lowest 10-Year Returns

The engineer would be unhappy. During its worst decade, gold bullion shed almost half of its real value. Stocks, too, sometimes suffered losses, though at different times than gold’s struggles, but their trough was nonetheless higher. For investors who needed their money back after 10 years, gold was the most dangerous of the four assets.

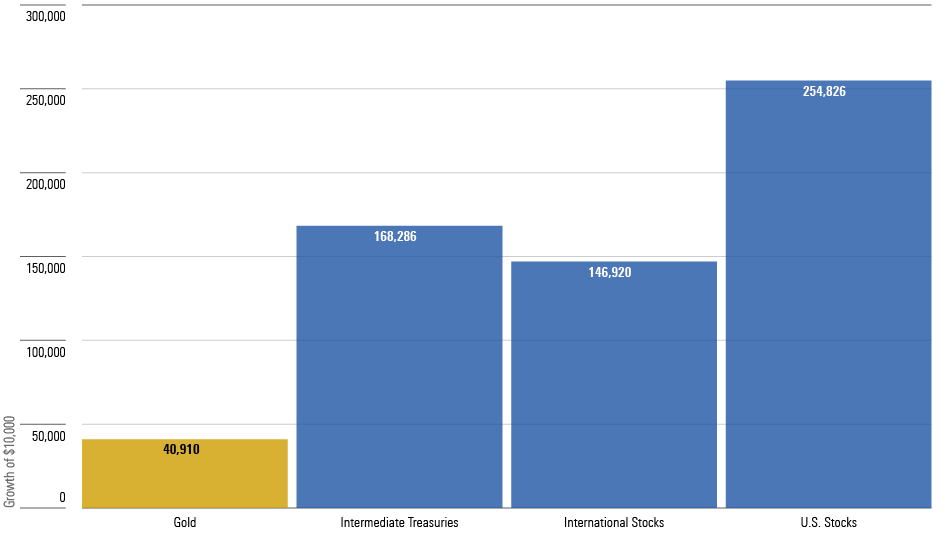

The 20-year view was worse yet. Gold dropped even further, to only 41 cents on the dollar. Meanwhile, the real returns on the three competing investments were invariably positive. Domestic stocks were especially spectacular, returning at least 154% through every 20-year period. They, not gold, were the overwhelmingly safe choice.

Lowest 20-Year Returns

It may be objected that gold’s 10- and 20-year troughs each originated in early 1980, when bullion prices spiked. Thus, these findings are deceptive because they are based on a single moment in a half-century of history. Yes and no. Although it is true that the worst long-term results derive from that year, most who bought gold from 1979 until 1983 also lost money, after inflation, for the 20-year period.

3) Amid Catastrophes

I have no chart for the third and final assessment: how gold performs when the normal investment rules no longer apply, such as during bouts of total war or hyperinflation. Not only have such calamities rarely troubled developed countries over the past century, but when they have, gold’s barter rate has not often been documented. The data permits only guesswork.

However, based on anecdotal evidence—including my mother-in-law’s experience as a World War II refugee, when she survived on meals purchased with gold coins from her mother’s attic—I will grant gold its due. Should complete disaster strike, gold should prove superior to both paper dollars and electronically stored cryptocurrencies. Sometimes, tangible assets beat intangible promises.

But those seem to me highly unlikely scenarios. However, I can neither deny the possibility nor the fact that if calamity does arrive, I will regret my decision not to own precious metals. Under those conditions, the engineer’s portfolio will outdo that of your humble (alleged) investment expert.

In short, the decision to invest in gold comes down to 1) the probability that an investor assigns to the prospect of international catastrophe and 2) the investor’s comfort level in ignoring that possibility. As an optimist, I find that an easy call: Forge ahead without it! However, I appreciate that others have different views. For them, a dollop of bullion may provide comfort worth its weight in...well, gold.

Based on this column’s evidence, though, I do not think the case for gold extends further than that.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HTLB322SBJCLTLWYSDCTESUQZI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/TAIQTNFTKRDL7JUP4N4CX7SDKI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)