Financial-behavior studies frequently suggest a difference between the behavior of women versus men. For example, studies like Odean’s and Barber’s “ Boys Will Be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment” found that men’s tendency toward overconfidence bias prompts them to trade more excessively than women, resulting in lost returns. On the other hand, studies concerning women’s financial behavior often find that women tend to be more risk-averse and take on more conservative investments, sometimes to their own detriment.

Our research suggests that these faux pas in financial behavior are not a result of lack of knowledge. Rather, many studies have found that investors tend to make the biggest financial mistakes in situations where emotions are running high. But in a low-pressure scenario, both men and women choose fairly optimal investing decisions.

Investors—both men and women—do know better

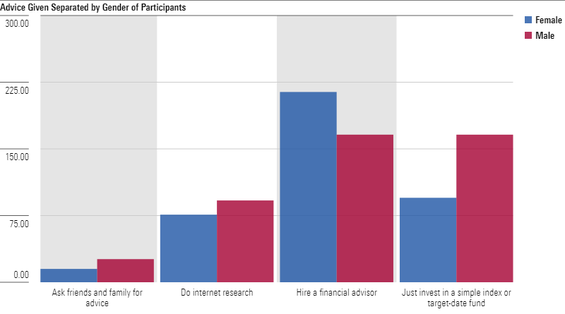

In our study, we presented individual investors with a situation in which a friend asked them for financial advice. In this scenario, the friend is 51 years old, has an annual income of $60,000, and recently received a windfall of $20,000. The friend wants to analyze this windfall investment option but isn’t sure how to get started. We asked participants to give the friend advice by selecting one of the following options:

- Hire a financial advisor

- Ask friends and family for advice

- Do research on the Internet and make their own investment decisions

- Invest in a simple index or target-date fund

The results suggest that both women and men would give optimal advice with only slight variations. Most investors advised their friend to talk to an advisor or invest in a target-date fund instead of doing research on their own or asking friends and family for advice—two activities connected to common biases and financial mistakes. In short, women and men do not significantly differ when it comes to giving optimal advice, as illustrated on the chart below.

Why aren’t people following their own advice?

These results raise the question of why investors still make financial mistakes, like overtrading or taking on too little risk, even though they intellectually know the right thing to do. Simply put, it’s because investors are human beings and are prone to behavioral biases that lead them astray when making investing decisions.

For example, they may be prone to recency bias—a tendency to overvalue the events that happened most recently—which can lead to behavior such as chasing after returns. Or they may experience overconfidence bias, which can prompt them to make risky decisions, like trying to time the market.

One way advisors can work with clients to combat these natural tendencies is to act as behavioral coaches and help clients manage their emotions when making investing decisions. This study again demonstrates that advisors can make a great impact by steering their clients in the right direction when their emotions get in the way of their logic.