Tick, Tick, Tick: For Active Funds, It's Time to Adapt (or Die)

In the future, the active-fund industry must shrink, cut prices, better-align with investors, and differentiate.

- Despite already losing ground, active funds are vulnerable to further incursions by low-cost passive funds.

- Passive funds could capture another 10 percentage points of market share in the next decade or so.

- To adapt, the active-fund industry must shrink, cut prices, better-align with investors, and differentiate.

Past, Present, Possible Future

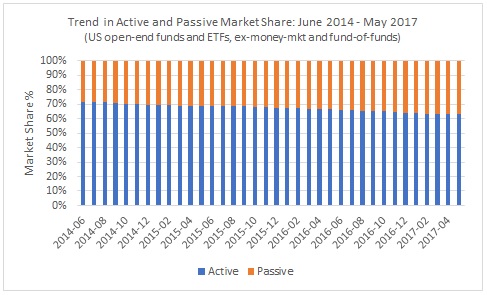

Actively managed funds accounted for about 63% of U.S. open-end and exchange-traded-fund assets on May 31, 2017. Only three years prior, it was around 72%.

Source: Morningstar Analysts

Given structural shifts in the market, which have been hastened by regulation and changing investor preferences, it's not unreasonable to think that passive will take another 10 percentage points of market share in the next decade or so.

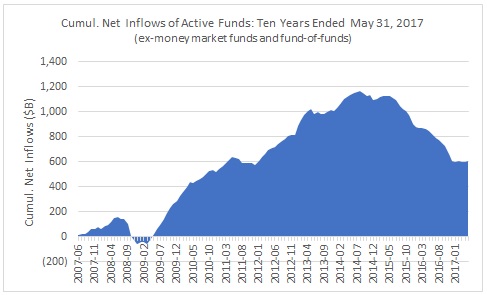

What does that translate to in dollar terms? Passive funds, including strategic-beta ETFs, recently held around $6.2 trillion of $16.5 trillion in U.S. fund assets. Given a semiconservative 4% annual organic growth rate on the U.S. fund industry for the next decade, that would vault passive assets to around $11 trillion by 2027. Depending on assumptions for sources of future growth (market appreciation or flows), that would imply at least $1 trillion in outflows from active.

To put that in perspective, even with the hardship of recent years, active funds still managed to rake in around $600 billion in assets over the decade ended May 31, 2017.

Source: Morningstar Analysts

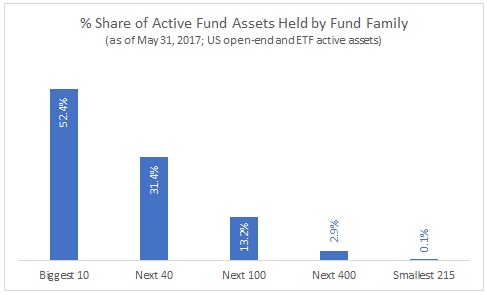

Shrink to Grow Would the industry be prepared for a sharp reversal? It does not appear so. As of May 31, 2017, there were 765 fund families that offered at least one active fund. The top 10 families accounted for 52% of the market, the bottom 500 a mere 0.8%. More than 500 families managed less than $1 billion, and around 280 managed under $100 million. In other words, the active-fund business is highly fragmented. Many subscale players will have to merge or shut their doors.

Source: Morningstar Analysts

This isn't necessarily new. There has always been a life/death cycle in the active-fund business, reflecting the industry’s attractive high-growth trajectory, potentially lucrative payoffs, easy entry, and attending high failure rate (easier entry makes for less fear of failure and, thus, more failure). But a few factors are likely to make this phase quite different and more lethal to vulnerable firms:

- The shift toward automation

- The pressure on distributors

- The preference for low cost

- Unbundling (alpha from beta; strategic-beta/factors from alpha)

Previously, the industry was largely unaffected by big technological and regulatory shifts. Fund companies had to adapt as business moved toward the web, but it didn’t fundamentally transform the way investment-management services were packaged and delivered to investors. This ensured that even upstarts had a shot.

However, the move toward passives, including strategic beta and factor investing, mechanizes investing, while innovations such as target-date funds automate tasks such as rebalancing. This does change the nature of investment management itself and, in turn, how value is perceived. Most notably, it exerts strong downward pressure on fees. Time was, fund companies had pricing power, a precious thing; alas, it appears they've lost that power.

It’s not just automation that’s seen to this. So, too, have dramatic changes in the way advice is rendered and priced. The opening up of platforms, increasing prevalence of fiduciary standards, and accompanying move from commission to fee-based business models have had a profound impact on advisors’ preferences.

They've flocked toward low-cost investments, passives in particular, which in part reflects changes in the way they position their value to clients, but also necessity: They had to find savings inside of the portfolios they were assembling, so as to keep the all-in cost of their service to clients in line with where it had been previously.

With that came other pressures: Distributors have leaned on asset managers to offer “institutionally” priced versions of their strategies, atop which they can layer their own fees. This challenges asset managers insofar as it can shift the cost for distributor platform access from the investor (paid out of fund assets via 12b-1) to the fund company itself (paid out of pocket). What’s more, amid heightened regulatory scrutiny and the need to economize, distributors have been purging hundreds of funds from their platforms.

Thus, whereas in the past firms could differentiate through some combination of boots on the ground and revenue-sharing (financed largely via 12b-1 fees), they now must pay for shelf space and compete to keep their place. This will put a further premium on scale and investment capability and put the squeeze on smaller players.

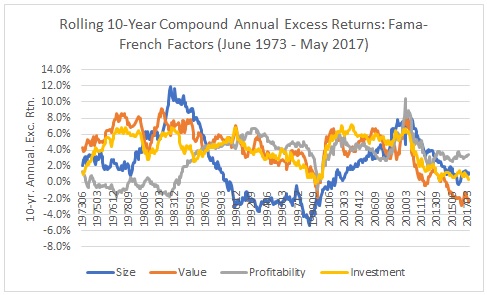

Distribution challenges notwithstanding, evidence suggests there are too many professional investors chasing too few ideas. Yes, this is felt more acutely in the later stages of an extended bull market, when ideas are scarcer. But pre-fee excess returns have trended lower over the past few decades, perhaps denoting a "skill glut" that is strangling opportunities for profit. This has likely been exacerbated by the discovery and increasing popularity of risk factors, which have shrunk some of these premiums. Net-net, active funds have had greater difficulty keeping up with their indexes in recent years. The game appears to have gotten tougher.

Source: Morningstar Analysts

Some of these performance woes are cyclical, and as those headwinds abate, active-fund performance is likely to perk up a bit. Moreover, a bear market should at least slow the mass migration toward passive funds. But the structural changes—toward automation, open architecture, low cost, and unbundling—appear irreversible. Given this, a smaller active-fund business isn’t just a possibility but a necessity: The industry likely must shrink to grow.

Cut Prices Not only must active funds shrink in number but many of the surviving funds also will need to cut prices.

In a recent study of U.S. equity funds, we found there were thousands of funds that charge annual expenses that exceed the average pre-fee excess return for their category. In other words, these funds--which collectively held around $2 trillion in assets--appear priced to fail. Their expense hurdles are too high.

What brought us to this point? The confluence of several trends:

Bundling Management and Distribution Expenses

While investment management is a scalable business--one doesn't need to hire dozens of new portfolio managers to handle each incremental billion in assets--distribution expenses tend not to be. Why? Because platforms and distribution hubs demand a more-or-less steady revenue-sharing stream from asset managers. While 12b-1 is capped, that doesn't preclude fund firms from padding their management fees to defray any extra distribution costs. All told, this has made running a fund a whole lot less scalable than logic would suggest, and it partly explains why expense ratios have remained stubbornly high.

Availability of Passive Funds

Index funds and ETFs used to be harder to access through advisors, some of whom were limited to “menus” of pricey proprietary funds or those of other firms that revenue-shared their way onto the select list of options. But those days are long past--cheap beta is seemingly everywhere. Given this, active funds’ fees are measured against the cost of passive alternatives, not necessarily other active funds. That’s a much tougher test, one that many active funds are flunking.

Competition Growing Stiffer

As mentioned, excess returns appear to have become scarcer in some areas, and active-fund success rates have fallen accordingly. In our most recent Active/Passive Barometer report, we found that only about 10% to 20% of active U.S. equity funds beat their benchmark over the 10 years ended Dec. 31.

In summary, the way forward is clear: Funds must cut prices and take steps to better share scale economies with their investors.

Align With Shareholders The time has come for fee structures and other incentive programs that more strongly align fund company interests with those of shareholders. This is not the first time I've taken up this cause: I wrote about the appeal of performance-based fees in the February/March 2015 issue of Morningstar magazine ("An Investor Friendly Fee").

In that piece, I argued that the old model of trying to pass off hope for alpha was not going to cut it in a world awash in cheap beta and rampant evidence of active's shortcomings. Instead, I suggested active funds should consider adopting performance-based (so-called fulcrum) fees as a way of differentiating, offering a number of potential benefits to investors, including:

Less Index-Hugging

There’s nothing to stop a manager from mirroring the benchmark and collecting a base fee. But this manager will lag by the amount of his or her expenses, if not more, a fact not lost on investors (many of whom are already abandoning closet-index funds for index funds and ETFs). If we want to create an incentive for managers to take prudent, well-predicated bets, a properly structured performance-based fee could do the trick.

Less Trading

Managers might be prone to feel like they need to “be active” to earn their flat (or, if investors are lucky, tiered) management fee. This can lead to shorter-than-healthy time horizons and wanton trading, which hurts performance before and especially after taxes. A performance-based fee isn’t an antidote to this problem but could act as a healthy deterrent, mainly in decoupling “trading” and “value-added.” For example, if investors in a fund realize that the manager won’t get paid full freight if he or she doesn’t beat the bogy, then they might be less insistent on seeing evidence that the manager had turned over the portfolio in the prior quarter. As that reality becomes clearer, investors and portfolio managers alike will realize that it’s not about trading for trading’s sake.

Less Bloat

Today, given the prevalence of flat management fees, funds are reliant on unit growth. That is, they must ramp up their assets to grow fees and keep all of the mouths in the organization fed. This can lead to asset bloat, as fund firms tend not to know when to say when to close a fund, and, by the time they do, it has outgrown its capacity. A performance-based fee could help to reduce the reliance on asset growth and create incentives for firms to proactively monitor capacity. If they didn’t, it would threaten performance and, thus, their ability to earn the performance fee, after all.

Less Product

Finally, because performance-based fees are harder to earn, they’re likely to repel new entrants to the industry and thin the herd of its weaker members. As I wrote in 2015, “There are still too many active funds, most of them marginal. A smaller pool of higher-quality funds is better for investors and, therefore, the industry itself over the long term."

Differentiate As of May 2017, there were nearly 2,100 unique active U.S. equity funds, more than half of which were large-cap funds. Do we really need this many active U.S. stock funds? The answer, of course, is no. And that takeaway probably can be applied to the broader active-fund complex, which seems overgrown and commoditized.

There’s little doubt that investors will continue to rely to a certain extent on past performance to differentiate even similar funds. But when index funds or ETFs can be had for less than 5 basis points in some cases, past performance ceases to be the catnip it once was. Rather, it takes something more.

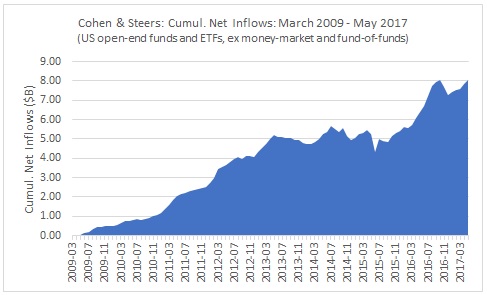

That something is differentiation--building a hard-to-replicate set of capabilities or carving out a toehold in a hard-to-enter, indexing-resistant niche. A good example is Cohen & Steers, an active fund complex that has notched positive net inflows in 76 of 98 months since the global financial crisis (as of May 2017). The firm has gathered around $8.1 billion in net fund inflows over that span.

Source: Morningstar Analysts

How has the firm managed it? It has been disciplined about carving out its niche--real estate--and largely staying within it. While Cohen lacks the diversifying traits of other, larger complexes, it has done a good job of varying its product mix and building a global following for its specialty. The firm has also chosen an area that is inherently tougher to index and that is known for generating plentiful income, factors that probably alleviate some pricing pressure and ensure that it has a strong following among yield-focused investors.

There’s room for only so many niche players, especially in a world in which scale and efficient reach is so critical. But Cohen has demonstrated that it’s possible to profitably differentiate. It’s a model that other firms would do well to at least consider.

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2017 issue of Morningstar magazine.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)