5 Ways Investors Can Succeed by Knowing Their Limits

You don’t know what you don’t know when investing.

Here’s what I know I didn’t know a few weeks ago. I know I didn’t know anything about Silicon Valley Bank SIVB. I know I didn’t know how a homogeneous depositor base could threaten the solvency of a bank like Silicon Valley. And I sure as heck didn’t know that, for a time at least, Silicon Bank’s insolvency (and a band of extremely online venture capitalists) could shake the financial system. This I now know.

I also know that my knowledge of what I didn’t know entering last week will be of almost no practical use to me going forward. I know this because I know I won’t know what I didn’t know entering whatever episodes like Silicon Valley might arise in the future. How do I know this? Experience—that is, being repeatedly confronted by events or variables I didn’t even know I was ignorant of to begin with.

And this is how I know I’ll get paid. For if I don’t know what I don’t know, and that’s true of virtually all of us (whether we’re prepared to admit it or not), then that means we’re mostly in the dark about potential future events and outcomes. We know we don’t know what we don’t know. And for that, we’re eligible for compensation in the form of an excess return that we can earn on the capital we make available.

Of course, eligibility to get paid and actually getting paid can be very different matters, with the two separated by a tangle of emotions and skewed incentives that can thwart our success. So, the key question is how to close the gap and ensure we’re duly compensated for putting our money at risk while knowing that we don’t know what’s in store for us. In this piece, I suggest five ways we can do so.

Diversify

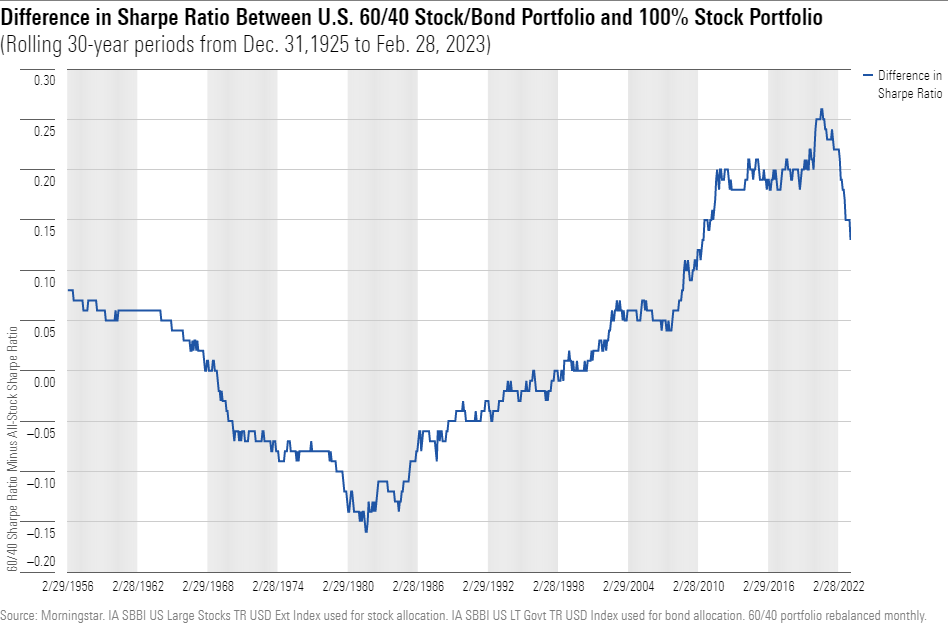

It might sound backward to argue that a way to ensure we get paid for taking risk is by offloading some risk, which is sort of what we do when we diversify. And, indeed, it’s true that there have been long stretches in which it has not paid to spread our bets across both stocks and bonds, as shown below.

Nevertheless, it’s a mistake to conclude that diversification failed investors over these long periods. Why? It doesn’t consider that an all-stock investor might not have earned the superior equity return. Rather, he might have gained far less, buying and selling at inopportune times because he couldn’t handle the surprises the market dished out along the way.

In that sense, I think of diversification not as a choice to forego but rather as a way to ensure we participate more fully in stock market returns than would otherwise be possible. We know issues will come out of left field, but we don’t know when or what impact they’ll have. Diversification cushions those blows, keeping us in our seats.

Hold Some Extra Cash

If we know that we don’t know what we don’t know, then it stands to reason we should give ourselves some breathing room when an issue suddenly bursts onto the scene. Last year, it was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In 2020, it was the emergence of the coronavirus. Twenty-five years ago, it was Long Term Capital Management’s implosion. Market history is full with episodes like these.

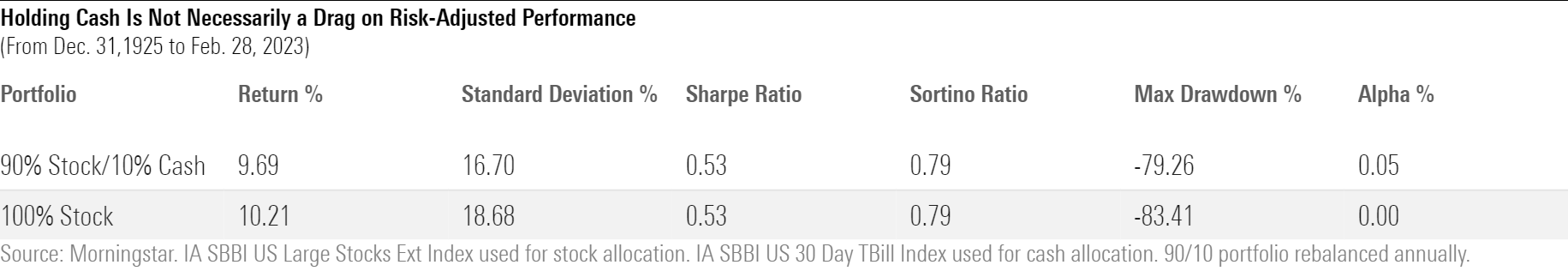

Keeping some dry powder isn’t without cost. When markets are rising, cash drags on our returns, holding us back. But its presence might make us less prone to act impulsively at times markets go haywire. What’s more, it can serve as a crucial source of funds that we can deploy to our advantage after markets retreat. Indeed, a portfolio split 90% and 10% between U.S. large-cap stocks and cash has generated about the same risk-adjusted performance as a portfolio invested entirely in stocks since 1925, as shown below.

Finally, holding a little extra cash can also confer a psychological benefit, serving as a built-in brake on our propensity for overconfidence, where we assume we know a little more about what the future holds than we really do.

Avoid Leverage

There’s a theoretical case one can make for investing with borrowed funds. For example, academics have argued that younger professionals ought to employ leverage given their longer time horizon, higher risk capacity, and the utility of freeing up available funds for consumption.

That’s good in theory but try meeting a margin call as the world seems to be crashing down around you. It’s a scenario we’re not well equipped to plan for, let alone work through in real time.

Leveraged investing succeeds as long as it’s not interrupted by unforeseen events that force us to sell to meet our obligations. Yet, we know we’re paid an excess return for courting the risk of being exposed to largely unforeseeable factors. In this way, leveraged investing seeks to have its cake—earn a premium return—and eat it too, that is, avoid the unforeseen events that earn us an excess return to begin with.

We jeopardize our ability to amass wealth when we short-circuit the compounding process by locking in losses. But that’s the Faustian bargain we strike when we invest with leverage.

Warren Buffett put it best: “If you don’t have leverage, you don’t get in trouble. That’s the only way a smart person can go broke, basically. And I’ve always said, ‘If you’re smart, you don’t need it; and if you’re dumb, you shouldn’t be using it.’”

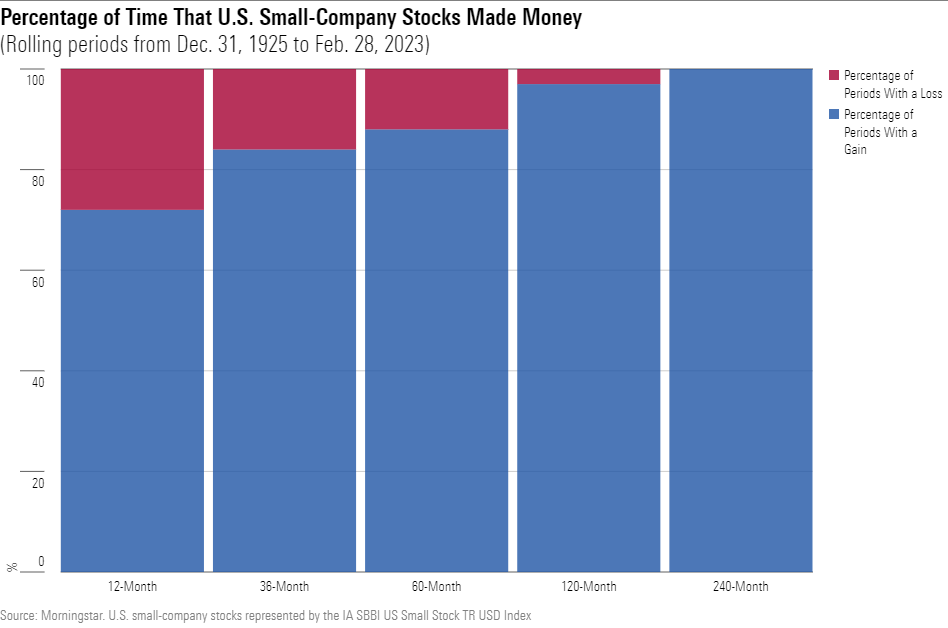

Sit on It

Since 1925, investors in the stocks of U.S. small companies have lost money in nearly one of every three rolling 12-month periods. But as you extend the rolling period to 36 months, 60 months, and beyond, your odds of making money go higher and higher. In fact, investors have lost money in small caps in only 3% of all rolling 10-year periods and have never failed to make money in a rolling 20-year period.

We may know we don’t know what we don’t know, but one thing we do know is that markets tend to reward us over the long haul. That strongly argues for sitting tight, come what may.

Remove Layers

Sometimes we can’t help ourselves from taking action when we ought to stand pat. But other times we essentially guarantee that others will act on our behalf when the best thing they could do for us is twiddle their thumbs.

I’m referring to situations in which we hire others to advise us. To be sure, there’s nothing wrong with financial advice. For some of us, it’s essential. But in investing, the more cooks in the kitchen, the likelier we are to be served a helping of cold, mushy gruel—or greater complexity and below-average returns.

For every layer of “deciders” between investors and the ultimate destination for their capital, there are more agency risks to navigate. For some of these deciders, like consultants, advisors, and subadvisors, their bread is buttered through certainty and action. “I don’t know” might score them points for honesty, but it’s not going to pay the bills. Thus, the more decisions to be made, the greater the risk of unintended consequences (to say nothing of high fees, with all those mouths to feed).

If we minimize layers and ensure that incentives align with our plans, we reduce the risk of unnecessary complexity, higher fees, and the toll they can take on our performance. If you know, you know.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/KWYKRGOPCBCE3PJQ5D4VRUVZNM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/TZEZ6FJNTZEZRC3FBWCWXTXVOQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)