Maximize Aftertax Returns With ETFs

A closer look at the sources of ETFs' tax efficiency.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2019 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Click here to download a copy.

Death and taxes may be the only guarantees in life, but exchange-traded funds and prudent tax planning can help defer the timing of those tax payments and maximize what really matters: aftertax returns.

Tax efficiency is a hallmark of the ETF structure. ETFs are less likely to distribute capital gains than mutual funds, and they tend to make smaller capital gains distributions when they do. That's partially because of differences in turnover. Most of the assets invested in ETFs are held in broad, market-cap-weighted index portfolios, which tend to have lower turnover than most active strategies, where the bulk of mutual fund assets are invested. Lower turnover means it's less likely a fund will have to recognize and distribute capital gains because it reduces the amount and frequency of sales in the portfolio. But that's not the most important part of the story.

Structural Advantage ETFs enjoy a structural tax advantage over mutual funds. This springs forth from differences in how money comes into and out of these two investment vehicles. When investors want to buy a mutual fund, they send money to the fund company in exchange for shares in the fund. The portfolio manager then uses that money to purchase securities for the portfolio. When there are withdrawals, the manager often has to sell securities to raise cash, which can trigger capital gains that must be distributed to all investors in the fund by the end of each year. This can create regular tax bills for long-term investors.

Withdrawals do not create a similar problem for most ETFs. Most of the time, when investors sell an ETF, they are selling on the secondary market to another investor who wants to buy. The fund company is not party to these transactions, so the only people affected by these trades are those who are engaging in them.

When a lot of investors want to sell an ETF, it can push the price of the fund below the value of the assets it owns (its net asset value). When that happens, authorized participants--a special breed of market makers--buy up ETF shares on the secondary market and turn them over to the fund manager. In exchange, the manager gives them shares of the underlying securities in the portfolio, allowing the APs to arbitrage the difference between the ETF's market price and its NAV. This in-kind redemption is a nontaxable transaction, and it allows managers to purge low-cost-basis shares from their books, making it less likely that they'll have to recognize capital gains.

Portfolio managers can't outsource all their trades, however, particularly those triggered by index changes. Here, they must manage their tax lots to mitigate the tax consequences of their trades, as they are required to distribute all their recognized capital gains to investors every year, just like mutual funds. But that's easier to do when it's feasible to remove low-cost-basis shares through the in-kind redemption process.

All of this works well when there are ample in-kind redemptions, but what happens if investors aren't interested in leaving, or if those redemptions don't coincide with the removal of stocks with big capital gains from the portfolio? Here's where things get interesting.

Heartbeat Trades When an ETF manager sees an index change coming that would require him to recognize a large capital gain, he may ask an AP to do an in-kind creation of ETF shares a few days before the index change takes effect, with the understanding that the transaction will be reversed a couple of days later. When the AP goes to withdraw its money, the portfolio manager delivers a custom redemption basket, consisting only of the stocks he needs to get rid of to avoid recognizing capital gains. That removes most of the unrealized gains from the books, so there is little if any tax consequence when the index change takes effect.

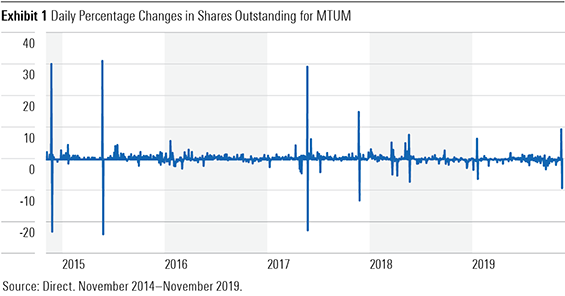

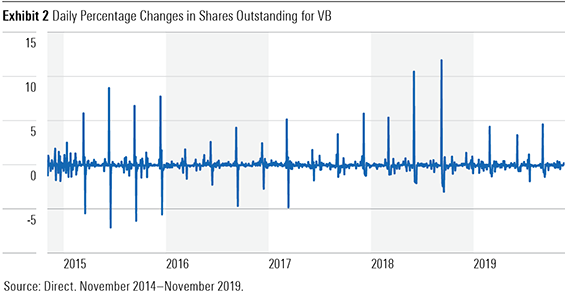

Because these large creations and redemptions happen in quick succession (usually a couple of days apart), they look like a heartbeat on an electrocardiogram monitor, hence their nickname "heartbeat trades" (coined by FactSet's Elisabeth Kashner). Exhibits 1 and 2 illustrate heartbeat trades in action for iShares Edge MSCI USA Momentum Factor ETF MTUM and Vanguard Small-Cap ETF VB, respectively. These show the percentage change in ETF shares outstanding from the prior day, which are based on creation and redemption activity.

There were large, temporary changes in the number of shares outstanding for MTUM in November 2014, May 2015, May 2017, November 2017, April 2018, May 2018, January 2019, and November 2019 (1). These heartbeat trades correspond to some, though not all, of the rebalancing dates for the index that the fund tracks. This has helped the fund avoid distributing any capital gains over its life, despite its high turnover, which is often more than 100% annually.

VB uses heartbeat trades more regularly, corresponding to its quarterly rebalancing schedule. These have helped the fund avoid capital gains distributions over the past 10 years.

Why do APs agree to these trades? It's hard to point to one factor, but they are likely seeking to curry favor with the asset manager in hopes of generating more business in the future. However, there's no guarantee that these trades will help the APs in any way.

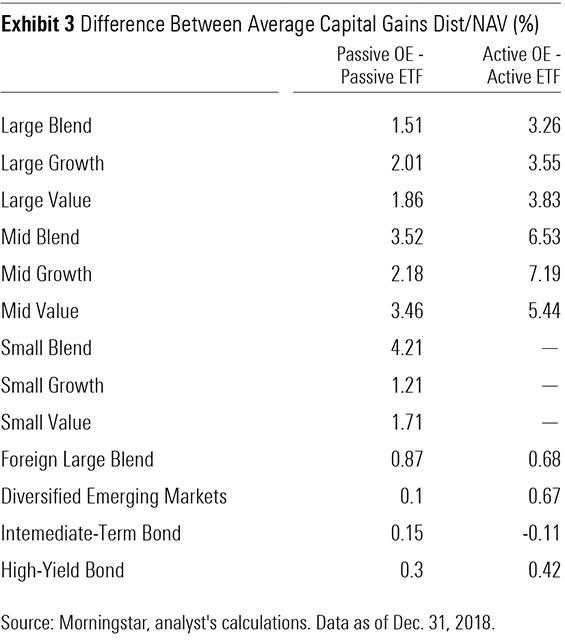

Sizing the Tax Advantage Given their structural advantages, which are most apparent in the form of heartbeat trades, it's no wonder ETFs tend to be more tax-efficient than mutual funds. Morningstar's director of global ETF research Ben Johnson and I quantified this tax advantage in a recent study (2). Exhibit 3 compares the average difference in capital gains distributions between ETFs and open-end mutual funds by Morningstar Category and strategy type, using data from 2004 through 2018, where available.

As expected, ETFs tended to make fewer and smaller capital gains distributions than mutual funds in almost every category. ETFs' tax advantage was generally greater among stocks than bonds. This is because capital gains tend to represent a smaller part of bonds' total returns than stocks', so the value of the capital gains deferral tends to be smaller here. Additionally, some ETF managers hold their bonds until maturity, where there is no chance to avoid capital gains. Cash redemptions are also more common among bond ETFs than they are among stock funds and don't provide the same tax advantage as in-kind redemptions.

We also compared passive ETFs and mutual funds matched by index. As before, ETFs tended to make smaller distributions. They were much less likely to make any distributions at all, as shown in Exhibit 4.

Tax-Efficient, Not Tax-Exempt While ETFs better defer capital gains taxes than mutual funds, they are not immune to taxation. Investors in ETFs will still pay taxes on regular distributions of income, and they will be on the hook for capital gains taxes when they sell an ETF for more than they paid for it. And some ETFs do distribute capital gains, though they tend to be less frequent and of lesser magnitude than most mutual funds.

Tax Management Strategies ETFs can form the foundation of a tax-efficient portfolio, but investors can take additional steps to improve tax efficiency. One of the most effective is strategic asset allocation between taxable and tax-advantaged accounts, including retirement accounts, health savings accounts, and 529 plans. Assets where a greater share of the total returns come from current income, like taxable bonds and high-dividend-paying stocks, should primarily go into tax-advantaged accounts. Such accounts can defer taxes on those distributions, while ETFs cannot.

Broad stock funds, especially international and municipal-bond funds, are better suited for taxable accounts. ETFs can defer unrealized capital gains taxes on broad stock funds, which will likely account for most of their return over the long term. On top of this benefit, U.S. investors in international-stock funds can claim the foreign-stock credit for taxes paid on foreign stocks to reduce their U.S. tax bill, but only when those shares are held in a taxable account.

Municipal-bond funds can also make sense for investors in the highest tax brackets, as their interest payments are exempt from federal taxes. Here, it's important to compare the yield of muni funds with the tax-equivalent yield of taxable bonds to gauge whether they are competitive.

Tax-loss harvesting is another effective way to improve tax efficiency. Losses can be a blessing in disguise. Recognizing them allows you to recoup part of the loss and move on to better alternatives. Fight the urge to hold on to losers in a taxable account when there are taxable gains elsewhere in the portfolio. Investments don't remember where you bought them, but the government sure does.

Endnotes 1) This index rebalanced off-cycle in May 2018 and at the beginning of February 2019.

2) Johnson, B., & Bryan, A. 2019. "Measuring ETFs' Tax Efficiency Versus Mutual Funds." Morningstar. https://www.morningstar.com/articles/940313/measuringetfs-tax-efficiency-versus-mutual-funds

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/07-25-2024/t_56eea4e8bb7d4b4fab9986001d5da1b6_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BU6RVFENPMQF4EOJ6ONIPW5W5Q.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)