Is Your Bond Fund Really a Stock Fund in Disguise?

Higher-yielding bond-fund categories often come with more stocklike risk levels.

One of the most basic decisions investors have to make is how to split their assets between stocks and bonds. After all, these asset classes are fundamentally different: Stocks represent an equity ownership stake, while bonds generate coupon payments with repayment of principal at maturity.

Stocks also come with far higher risk levels. Over the 20 years ended Dec. 31, 2021, the Morningstar US Market Index clocked in with a standard deviation of 15.32%, compared with just 3.31% for the Morningstar US Core Bond Index. This higher volatility level also translates into far greater risk of loss during market downturns. During a down year for the market, stocks might be down 10% or more, while broad investment-grade bond benchmarks typically lose 1% or 2% (barring a significant hike in interest rates).

But, in practice, the lines can be a lot more blurry. In this article, I'll discuss why some popular types of bond funds have more in common with stocks than you might expect. I'll also explain the implications for portfolio construction.

The Hunt for Yield

Yield is an increasingly scarce commodity these days, and it's even more hard to find given resurgent inflation. With the 10-year Treasury yielding about 1.7% as of this writing, most fixed-income investors are actually losing money in real terms. This has prompted many investors to look further afield in search of yield.

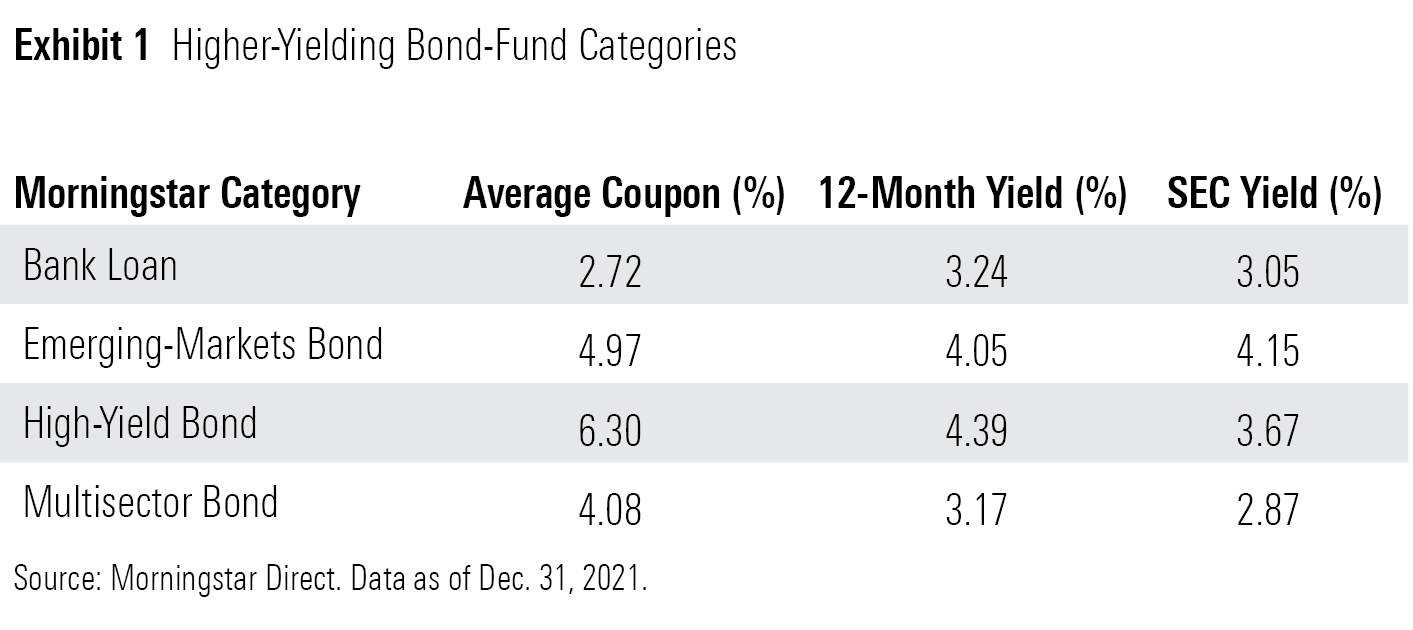

Some of the most common areas include bank-loan funds, emerging-markets bond funds, high-yield bond funds, and multisector bond funds. These Morningstar Categories currently sport SEC yields of 3.0% or more, compared with about 1.3% for intermediate-core bond funds, which is the most widely used fixed-income category based on asset size. Although investors have generally steered clear of high-yield bond funds in recent months because of lingering concerns about credit quality, the three other categories below attracted about $74.6 billion in combined net inflows for the year-to-date period through Nov. 30, 2021.

The Risk Trade-Off

Returns for most bond funds are typically determined in large part by movements in interest rates. In contrast, most higher-yielding bond funds tend to be less sensitive to interest rates, partly because the underlying businesses tend to benefit in improving economic environments when rates are going up. As a result, credit-sensitive bonds (with the exception of emerging markets) held up better than higher-quality bonds as interest rates edged up in 2021.

While interest-rate risk is less of an issue, higher-yielding categories are subject to a broader range of risk factors. Bank-loan funds, for example, invest in secured loans issued by below-investment-grade companies. These loans have floating interest rates that typically reset every 30 to 90 days. On the negative side, though, bank loans are subject to significant credit risk.

Emerging-markets bond funds generally focus on bonds issued by countries that are transitioning to more developed economic systems and capital markets. Emerging-markets debt is inherently riskier than debt from developed economies because of higher levels of political and economic instability. This risk periodically comes to the fore in the form of higher inflation, weaker economic growth, or rising current account deficits.

High-yield bond funds invest in bonds issued by companies with below-investment-grade credit ratings. In contrast to bank loans, these bonds rank lower on the capital structure and may not be backed by the borrower's assets in the event of a default, making them even more exposed to company-specific risk.

Finally, multisector bond funds seek income by diversifying their assets among several fixed-income sectors, including government bonds, corporates, international bonds (including emerging markets), and high-yield debt. Because they typically hold at least a third of their assets in bonds that are unrated or below investment grade, they can also be subject to significant credit risk.

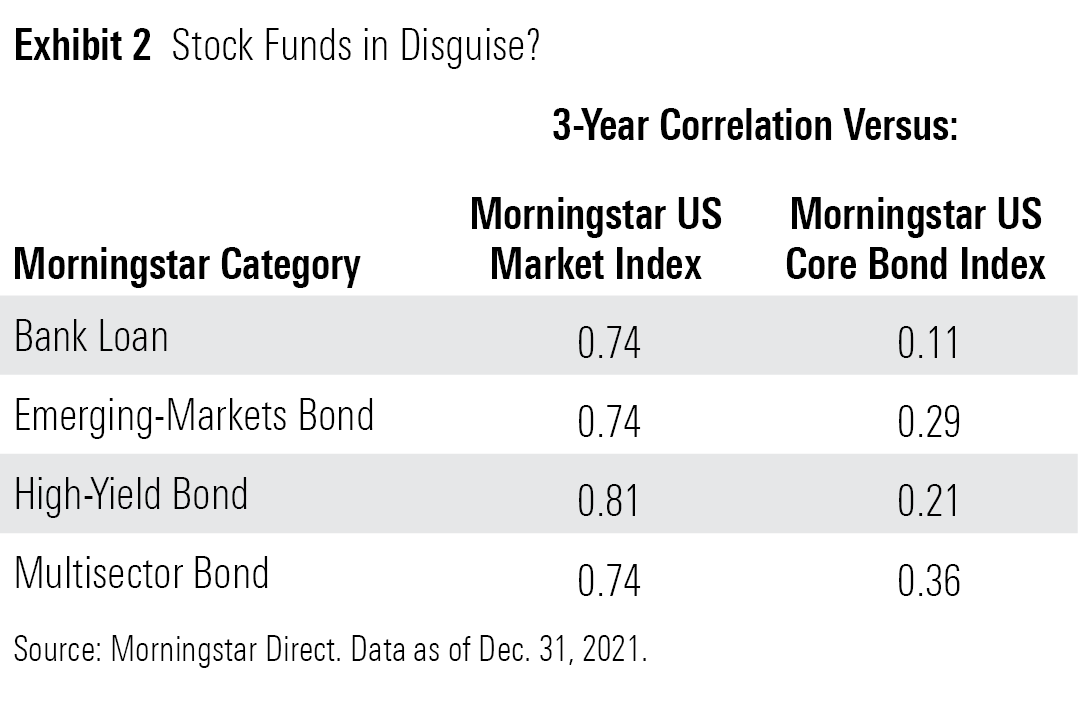

While the specific risk factors vary by type of fund, the common thread is that these higher-yielding categories don't really act like bonds. In fact, each of the four higher-yielding bond categories has a much closer link to stocks (as measured by the Morningstar US Market Index) than bonds (as measured by the Morningstar US Core Bond Index). As shown in the table below, the three-year correlation coefficients for these categories versus the equity benchmark range from 0.74 to 0.81.

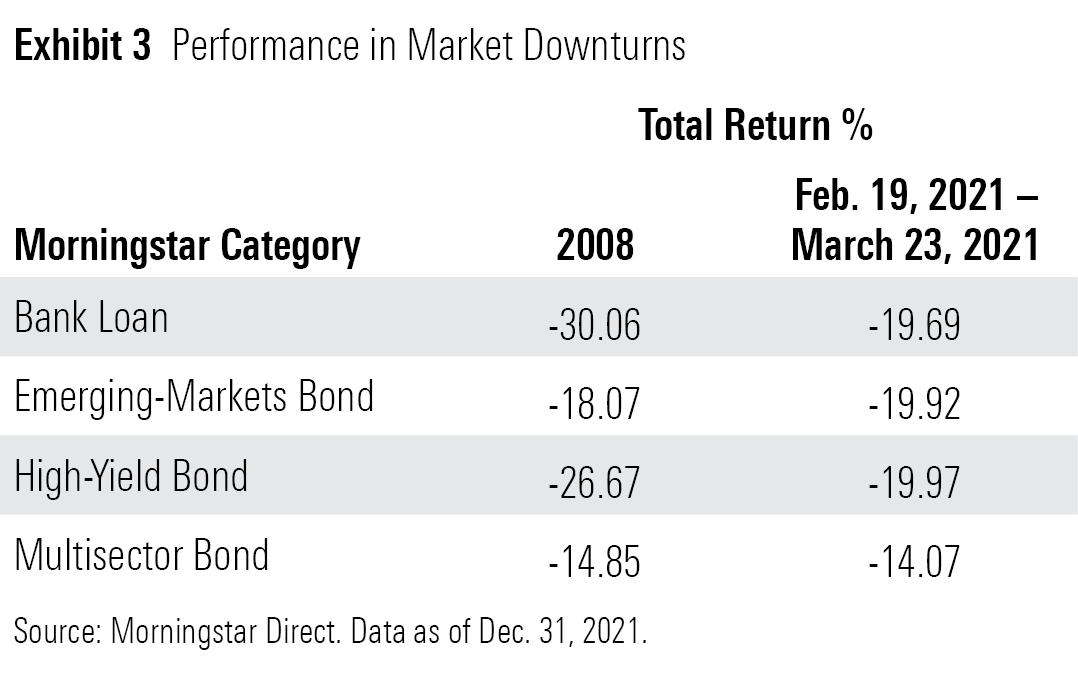

The closer equity links of these categories make them less effective for portfolio diversification and risk reduction. During the 2008 market correction in the wake of the global financial crisis, for example, most of these equitylike bond categories suffered losses of at least 15%. They held up better than stocks (which were down about 37%, on average) but suffered far deeper losses than investment-grade bond funds, which were down only about 5%. Bank-loan funds and high-yield bond funds were hit particularly hard thanks to their underlying credit risk.

The novel coronavirus-driven bear market in early 2020 is another case in point. The higher-yielding, equitylike bond categories held up better than stocks (which lost about 34% of their value from Feb. 19, 2020, through March 23, 2020) but still lost at least 14%, on average. Investors who bought these funds hoping they would serve a traditional fixed-income role as buffers against market downturns were probably sorely disappointed.

Lessons for Portfolio Construction

Investors who still want to add higher-yielding bond funds to their portfolios will therefore have to think carefully about how to incorporate them. From an asset-allocation perspective, one option is to think of these funds as equity substitutes instead of part of a traditional fixed-income allocation. More traditional types of bond funds--such as intermediate-core bond funds, short-term bond funds, and inflation-protected bond funds--do a far better job filling traditional fixed-income roles, namely risk reduction and buffering equity market risk. The trade-off, of course, is that they don't provide much yield these days.

Investors not willing to sacrifice current income can turn to higher-yielding bond fund categories as part of their portfolios' fixed-income allocation but have to be willing to accept much higher levels of drawdown risk in exchange.

Finally, it's critical to keep fund expenses top of mind. Many specialized bond funds have significantly higher annual expense ratios than their plain-vanilla counterparts. Because expenses come directly out of returns, higher expenses translate directly into lower long-term performance. In addition, they create an additional hurdle for portfolio managers, who often take on more risk to overcome the negative impact of expenses on both current income and total returns.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/06-11-2024/t_a4a9c8e4b4944a9fab91f0fccfde5dcc_name_MIC_24_Jerome_Schneider_Speaker_1920x1080.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/AGAGH4NDF5FCRKXQANXPYS6TBQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)