Understanding the 4 Key Annuities Types

Annuities can offer valuable protection against outliving your assets, but they can also be high-cost and complicated. We dig into some pluses and minuses.

There’s a long list of reasons consumers tend to avoid annuities, despite reams of academic literature suggesting that, used correctly, they can be of real help during retirement.

One reason might be that buying an annuity generally requires handing a chunk of money to an insurance company for the rest of your life, a trade-off that unnerves some savers. The way they are sold could also be a factor: Many consumers have become leery of the commission-based advisors that are more likely to sell annuities. Plus, dubious sales tactics sometimes employed around annuity sales have to some degree tainted their reputation.

Or perhaps it’s even simpler than that: Many annuities are complex and often lack transparency. As a result, savers have gotten scared away from even those annuities that are quite simple and relatively easy to understand.

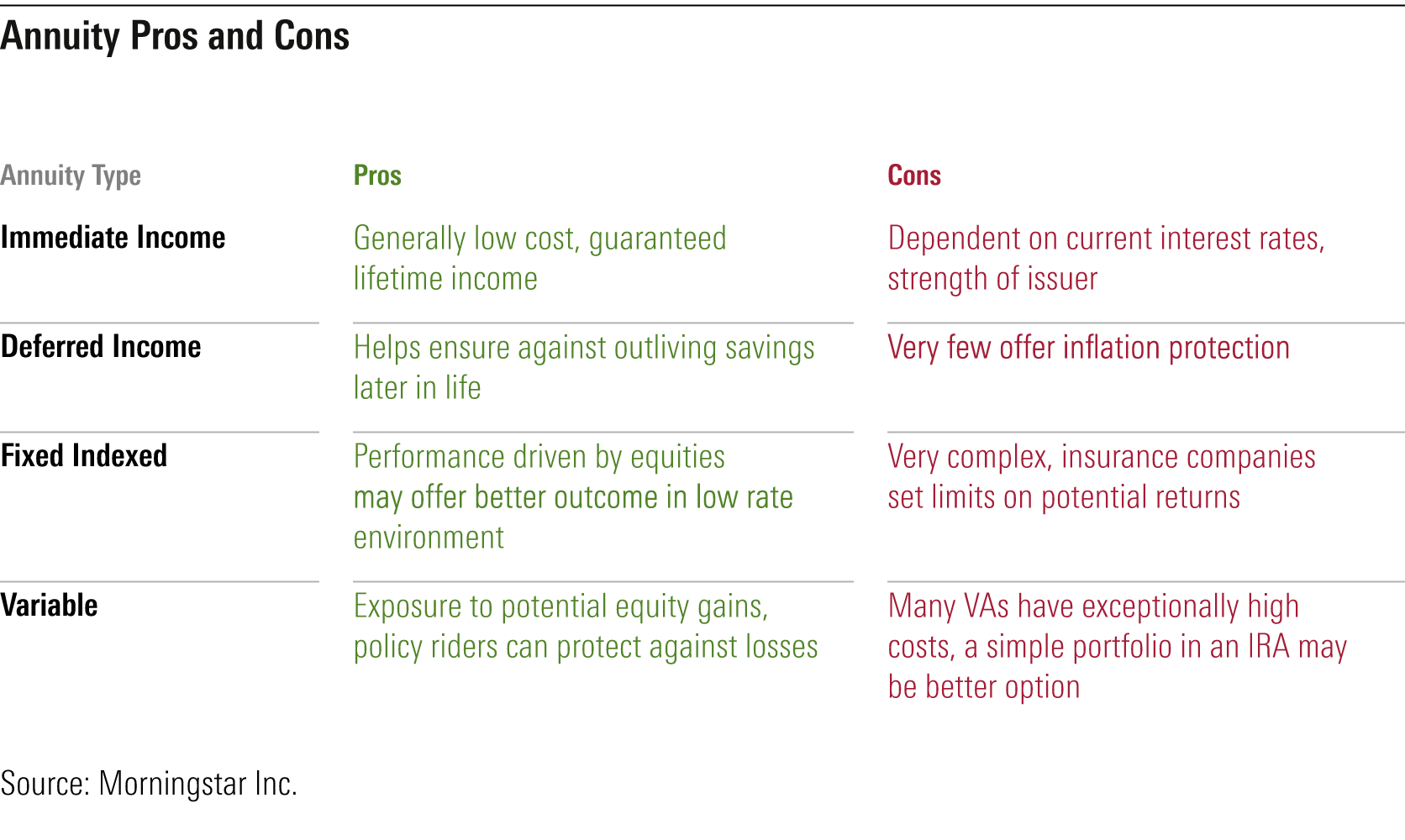

In this special report, we’re aiming to provide a series of educational articles about annuities. Here, I’ll take a closer look at four of the key annuity types: what they are, along with their benefits, costs, and key issues to assess if you’re considering one. It’s reasonable to think of them as a gradation, from least risky to most risky.

Immediate Income Annuity How It Works: Sometimes also called single premium immediate annuities, or SPIAs, for short, these are the simplest annuities. They've been around for ages, and they're the product type often referenced in the academic literature as being additive to retirement plans. The basic idea is this: You give an insurance company a chunk of your money, and in exchange it sends it back to you as a fixed stream of income payments for the rest of your life (or for a predetermined period of time). For example, a 70-year-old female buying an immediate annuity with $100,000 today would receive about $580 in monthly income for the rest of her life, according to Immmediateannuities.com. From that standpoint, such a product can be a complement to Social Security in that it's a guaranteed benefit that you can't outlive, provided your insurer makes good on its obligations. At the same time, "it almost always make sense to delay claiming Social Security retirement benefits before buying a private annuity," says David Blanchett, formerly of Morningstar and now head of retirement research for PGIM.

Who It's Best For: Simple immediate income annuities can be most attractive for people with tight retirement plans looking to ensure that their basic living expenses are covered by income sources that won't run out. In turn, they can invest their portfolios more for discretionary expenses. Needless to say, people who are buying an annuity for guaranteed lifetime income should have longevity on their side, in that you benefit most from such a product if you live longer than the actuarial tables suggest you will and lose out if you live a shorter period of time.

Pros: Given that only 20% of workers are covered by pensions today, the guaranteed lifetime income afforded by immediate income annuities is their biggest attraction. Moreover, such annuities typically pay higher yields than pure investment products, largely because some of the annuity buyers in the pool will die earlier, plumping the total payments for all and making long-lived annuity buyers the winners. On the other hand, the payout you receive from an annuity isn't directly analogous to the yield you earn from a bond. That's because part of the "return" from an annuity is your own capital being sent back to you as a stream of income. This type of annuity also tends to be the lowest cost and most transparent of all annuity types; there aren't any hidden fees to watch out for. That makes comparison-shopping straightforward. And as with all annuities, there's an element of tax deferral associated with the product, though how much of a tax benefit depends on whether you used "nonqualified" (aftertax) dollars or "qualified" (tax-deferred) funds to purchase it.

Cons: There are a couple of drawbacks to bear in mind with immediate income annuities. One is inflation protection: Fixed annuities often offer optional inflation protection, but adding that protection can dramatically reduce the starting income level.

Moreover, the product is only as good as the insurer behind it, which makes it important to focus on annuities offered by companies with high financial strength ratings. At the same time, note that major insurers are generally well capitalized and have the backstop of state guarantee agencies if they should run into problems. It’s also worth noting that the payout you earn from an annuity depends in no small part on the interest rates that the insurer can earn through investing the annuitants’ money. With interest rates as low as they are today, annuity payouts are also low relative to historic norms--but then again, bond and cash yields are also quite low today, too.

Managing insurance-company risk and the risk of purchasing the annuity at secularly low interest rates are key reasons that some experts who are enthusiastic about SPIAs recommend that "laddering" them--buying them in stages over several years--beats buying an annuity with a single purchase. The counterpoint, says Blanchett, is that you lose the implied mortality benefits you would earn by buying the product in a single purchase.

Finally, the richest payouts accrue to annuity buyers who are purchasing an annuity for their lifetime only, rather than a joint benefit or for a specific time period; adding additional guarantees reduces the starting payment accordingly.

Deferred Income Annuity

What It Is: These products, often called DIAs for short, are quite similar to the aforementioned immediate annuities. The key difference is that with a deferred income annuity, your payments start at some later date. For example, according to Immediateannuities.com, a 70-year-old female purchasing a deferred income annuity with $100,000 today would receive $2,428 per month starting at age 85. That's $1,850 more per month than the same purchaser would receive by buying a SPIA, but that's because the payments won't start until 15 years from now.

Who It's Best For: Deferred income annuities are best suited for retirees who feel confident they have enough retirement assets to sustain them through a specific period of time--to their average life expectancy, for example--but are worried about outliving their assets if they happen to live well beyond that. Among retirement researchers, these products are considered among the most effective hedges against outliving your assets.

Pros: Because these products are purchased well before they begin making payouts and because some buyers may die early, even before they've started receiving payments or shortly thereafter, deferred income annuities can provide a lot of bang for the buck, enabling buyers to purchase a significant bulwark against outliving their assets later in life. Moreover, one type of deferred annuity, called a qualified longevity annuity contract, or QLAC, allows an individual to steer up to $145,000 ($290,000 for married couples) from an IRA into a deferred annuity, thereby reducing the amount of the IRA that's subject to required minimum distributions. That said, research from David Blanchett and Michael Finke suggests that it's generally better to purchase annuities with aftertax dollars.

Cons: As with all other annuity types, insurer risk is a consideration, underscoring the importance of researching financial strength. Moreover, inflation could seriously erode the purchasing power of payments when you eventually begin receiving them. Very few deferred income annuities offer inflation protection, and policies that include cost-of-living adjustments tend to offer substantially lower payouts in exchange.

Fixed Indexed Annuity What It Is: While the aforementioned income annuities tend to offer low fixed payouts in exchange for stability, fixed indexed annuities, alternately called equity indexed annuities, aim to balance growth with loss avoidance. Designs of these products vary, but they generally use options to provide returns that are based on an equity index while also limiting losses. In other words, your downside is capped, protecting you, but your upside potential is also capped, protecting the insurer's profitability. For example, if the index that an annuity is linked to has a 10% return but the "participation rate" is 70%, then a 7% return would be credited to the account owner. These crediting details often change every year as market conditions--especially option prices--change. From a practical standpoint, the long-term returns on equity indexed annuities tend to fall between stocks and high-quality bonds. Some of these products offer death benefit protection.

Who It's Best For: These products may be appropriate for investors who are seeking some growth potential but are skittish about the downside volatility associated with pure equity investments.

Pros: Fixed annuities, whether immediate or deferred, offer payouts that are heavily influenced by prevailing bond yields, which are ultra-low today. By contrast, fixed indexed annuities derive most of their returns from equity-market growth while also offering protection against losses. Given their potential to earn a higher rate of return than bonds but with a similar element of downside protection, some experts have argued that they're a reasonable alternative to bonds in today's ultra-low-yield environment.

Cons: While these products offer protection against losses, they are far from free. "Caps" and "participation rates" cut into the percentage of equity-market returns that buyers of these products typically enjoy, and they'll fluctuate based on option prices. The products can also be incredibly complicated; it can be difficult to understand the terms and to comparison-shop among them.

Variable Annuity What It Is: While basic income annuities have very little risk and low return potential to match, variable annuities can entail a fair amount of risk, depending on what the account owner invests in. Whereas the insurer directs the investment mix in the aforementioned products and in turn determines the risk/reward profile, a variable- annuity owner is in the driver's seat, selecting among mutual-fund-type accounts called subaccounts. The subaccounts on offer typically range from ultrasafe to higher-risk. The account value ebbs and flows based on those choices. The account owner also has the potential to annuitize--essentially, to switch on a stream of payments--but in practice, more than 90% of variable-annuity owners never do.

Variable annuities also have insurance features called guaranteed lifetime withdrawal benefits, or GLWBs, which offer guaranteed lifetime income, albeit with an added cost.

Who It's Best For: Because they offer an element of tax deferral, variable annuities tend to be most appropriate for investors who have already maxed out their contributions to other tax-deferred vehicles such as IRAs and are seeking additional avenues for deferring taxes. But their high costs can dilute that benefit, as well as the long-term growth potential that comes along with the ability to invest in higher-risk assets like stocks.

Pros: Because of the broad array of investment types on offer within a variable annuity, these products enable account owners to build well-diversified portfolios of investments and potentially capture more equity-market growth than would be the case with income annuities or equity-indexed annuities. They also include an element of tax deferral, discussed above. A key attraction of variable annuities are living benefit riders like GLWBs. These riders are similar in spirit to the equity indexed annuities, discussed above, in that they offer downside protection but generally do not cap the upside. However, those features are far from free.

Cons: Although fees tend to be widely dispersed overall, some variable annuities feature exceptionally high costs, which can erode their growth over time. Thus, investors seeking growth who don't also have a need for the additional benefits the annuity confers may be better off investing in an IRA or brokerage account. It's possible to obtain a decent amount of tax deferral with lower overall costs by buying and holding plain-vanilla exchange-traded funds or index funds in a taxable account.

Could Your Portfolio Use a Makeover?

for a chance to have Christine Benz review your portfolio and provide improvement suggestions based on your needs.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/66112c3a-1edc-4f2a-ad8e-317f22d64dd3.jpg)