Should I Start Investing With Stocks or Mutual Funds?

You should probably start with a fund. Here's some advice on getting started.

Many new investors might put their money in stocks because they offer the best potential long-term returns. If you have years or decades to invest, as many beginning investors do, you can invest in stocks and see your dollars multiply over the time period.

But you might wonder whether you should buy individual stocks or an equity fund, which is a basket of stocks. While it doesn’t have to be an either/or decision forever, beginning investors are often better starting with funds because they offer some conveniences. We take a closer look at why and give some advice on how to choose a fund.

Diversification Is a Fund's Main Benefit One risk of holding only a handful of individual stocks is that if a few failed, it could have a big impact on your overall return. This is called unsystematic or business risk; it's the chance that company-specific issues like poor management or lawsuits could cause a stock's price to permanently plummet. The good news is that you can eliminate this risk by owning many companies, which is called diversifying. When you diversify by owning many stocks, the performance of the overall portfolio would be only minimally affected by a few poor performers.

As most funds have dozens (or hundreds) of holdings, you can diversify away unsystematic risk with just one fund in many cases. For many beginning investors, that shortcut is a huge advantage compared with buying and researching individual stocks.

You might also benefit from other diversification shortcuts that funds offer. There are also risks if you concentrate your portfolio in a specific sector or geography because that area may perform poorly and hamper your returns. With mutual funds, the portfolio often contains companies across sectors; if you add an international fund or two, you can easily own companies from around the globe (this also spreads your bets across more currencies).

However, diversification comes with a drawback: It lessens the impact of high-performing stocks, which some investors might seek. But as Alex Bryan discusses, it’s difficult to beat the market, and you face even more difficulty if you’re just learning the ropes. Many beginners will find that diversification’s downside protection outweighs losing out on the small chance of sky-high returns.

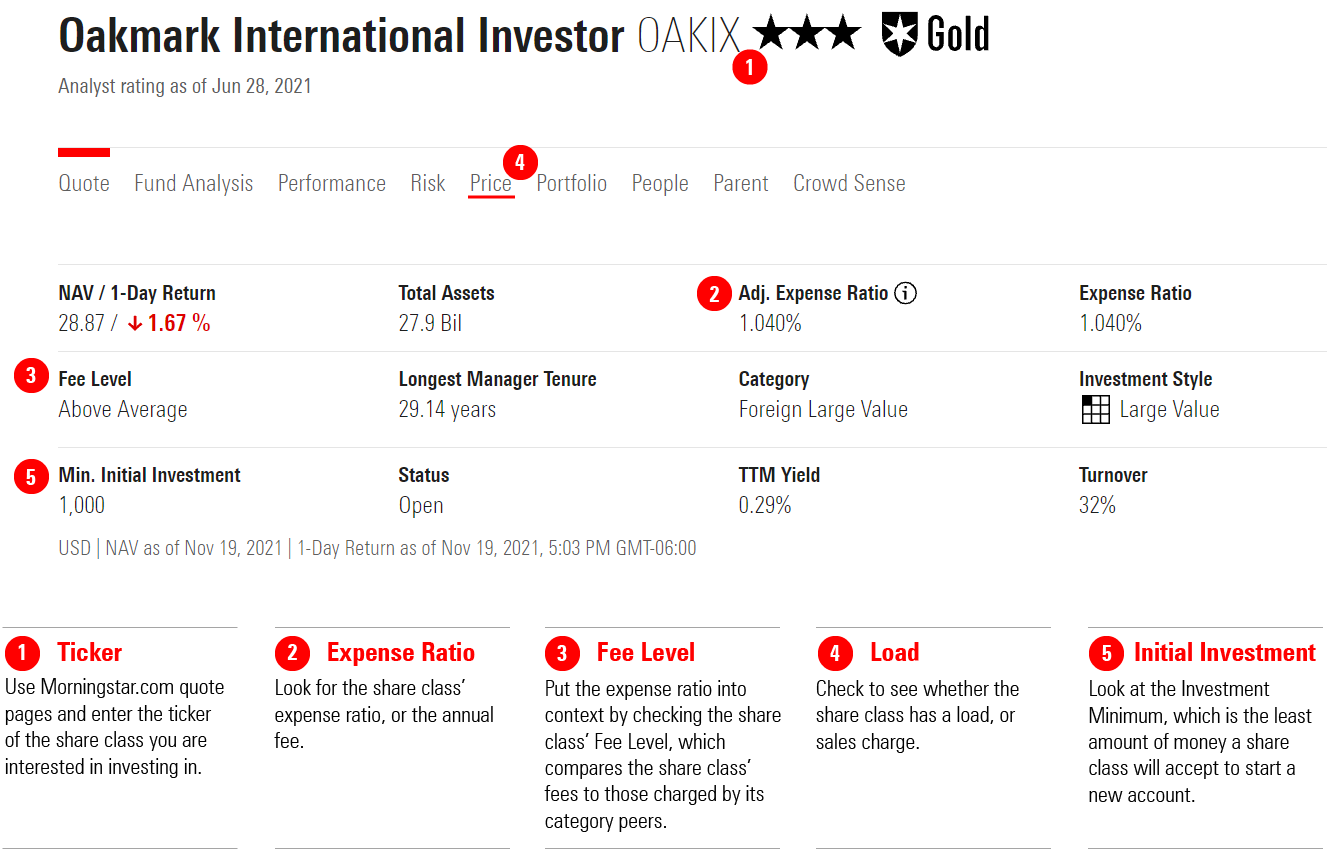

Using Morningstar Research to Choose a Fund While a fund can offer shortcuts, beginning investors must still perform meaningful due diligence to find the right pick(s).

If you're looking for some help, you can use Morningstar's research. We assign many funds a Morningstar Analyst Rating, which expresses our confidence in whether a fund can beat or mirror its benchmark's return going forward depending on whether it's an active or passive strategy (more on that difference later). For funds that our analysts like, we assign Bronze, Silver, and Gold medalist ratings, with Gold expressing our highest level of conviction.

Evaluating and Choosing the Right Fund(s) for You You might notice that Morningstar awards Medalist ratings to hundreds of funds in many different Morningstar Categories. As a first step, you'll need to determine what type of fund you're looking for. One area of the market investors often use for core stock exposure is the large-cap blend category, which contains large, multinational businesses across many different market sectors. For core foreign-stock exposure, many investors opt for funds in the foreign-stock large-blend categories. Another option is a target-date fund, which contains various underlying funds that combined can satisfy an investor's diversification needs.

You can use Morningstar research to find a topnotch choice in your preferred area(s) of the market. That's because Morningstar analysts rank funds relative to peers in their Morningstar Category, or Morningstar-created peer groups that cluster together similar types of funds. If you choose a Gold-rated U.S. large-blend fund, you know that our analysts have high conviction in that fund relative to other large-blend funds.

Once you've zeroed in on a category or two, you’ll need to carefully consider your preferences and circumstances to determine the best fund for your needs. Here are some key considerations:

Active or Passive You'll have to decide whether you want a passive or active fund. A passive fund's goal is to replicate the return of a designated market segment, and an active fund seeks to outperform the market segment.

Why would an investor choose a fund that won’t beat the market, you might ask? Many active fund managers underperform in the pursuit of beating the market (and active funds tend to charge higher fees), which can make the average return of passive investments appealing. (For more on the decision, see "What Is Passive Investing?")

Traditional Mutual Fund or ETF You'll also have to decide whether you want a traditional mutual fund or an exchange-traded fund, which is a fund that trades on a stock exchange. ETFs are typically passive investments, which means they track an index.

Beginning investors won’t notice many huge differences between traditional mutual funds and ETFs, so they can usually choose either (or a mix of both). One notable difference that Ben Johnson highlights is that ETFs have a tax-efficient structure, so you might prefer an ETF if you’re in a taxable account.

Costs You'll want to carefully consider a fund's costs because every penny paid in fees is a penny that's no longer available for you to invest. It's easy to find a fund's costs using Morningstar.com quote pages. Here's how:

- Enter the ticker (1) of the share class you want to invest in to pull up its Quote page.

- Look for the fund's expense ratio (2), or the annual fee that covers various costs, including the costs associated with managing the fund and selecting investments; administrative costs; and fees associated with brokers that facilitate the purchase and sale of funds.

- To put the expense ratio into context, you can also check the fund's Fee Level (3), which compares the fund's fees against those charged by category peers.

- You can also see whether the fund has a load (4), or sales charge.

Investment Minimum Many mutual funds have an investment minimum (5), which is the least amount of money a fund will accept to establish a new account. Some funds have $0 minimums, while others can range from hundreds to thousands of dollars for share classes that are available to individual investors. (If you're unsure what a share class is, see Karen Wallace's How to Choose Among Fund Share Classes.)

If you require a small investment minimum, you do have some options:

- Some funds have a $0 investment minimum, so you could choose only funds that meet these criteria.

- You can buy most ETFs for a specified price that's usually a few hundred dollars at most.

- You can gain access to funds for less than the investment minimum in many employer-sponsored retirement plans, like a 401(k).

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/b70d0063-c0bd-47f4-a1f5-74ff9b0435b1.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/b70d0063-c0bd-47f4-a1f5-74ff9b0435b1.jpg)