How to Advise Extraverts

Contributor Michael Pompian offers ideas for working with this personality, which is prone to overconfidence.

This is the fourth article in a series focusing on the Big Five personality traits and how they relate to the behavioral biases of investors. Over the years, I have followed a debate between the effectiveness of the Myers-Briggs test versus another widely used personality test, the Big Five. More recently, the debate has intensified. I decided to conduct a study of the Big Five. Specifically, I studied 121 investors, examining the relationship between the Big Five and investor biases. Why? Because taking the time to understand the underlying personality of the investor leads to better advice and results.

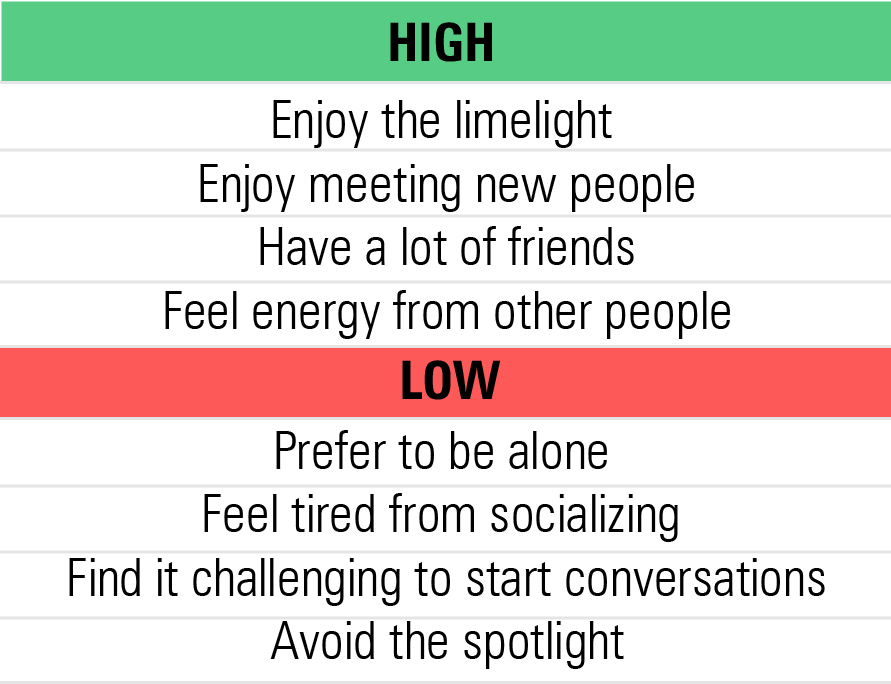

This month's article suggests how to advise extraverts. As a quick refresher, extraversion (also known as extroversion) is a trait described by talkativeness, assertiveness, and expressiveness. People high in extraversion are outgoing and get energy from the people around them. Being in social situations makes them feel energetic or even excited. People who are low in extraversion (also known as introversion) tend to be reserved and have to expend energy in social settings. They often prefer to be "in the corner" away from others.

Behavioral Biases of Extraverts As we learned in the last article, nearly four out of five extraverts were subject to overconfidence. Moreover, they want to influence decision-making or even control the decision-making process, which potentially can diminish an advisor's role. At their core, extraverts are typically risk-takers and are firm believers that whatever path they choose is the correct one. Overconfidence sometimes leads these types of clients to think they can control the outcomes of investments full of unknown risks.

Another aspect of extraverted/overconfident investors is that they can let their spending get out of control at times. In my experience, this client type's risk tolerance is quite high, but when things go the wrong way (and the client loses money), discomfort can also be very high. This discomfort may arise not only from financial loss but also from the blow to the client's confidence and the realization that he cannot control the outcomes of his investments.

Extraverts can be quite difficult for advisors to build close relationships with, because these clients are attempting to make their own decisions rather than relying on the advice and counsel of their advisors. Left unadvised, overconfident extraverts often trade too much, which can be a drag on investment performance. Finally, some extraverts can be difficult to advise because they do not believe in basic investment principles, such as diversification and asset allocation.

Upside and Downside of Extraverts Certain benefits accrue to extraverts. Extraverts are confident in their abilities, and they put their investment ideas into action. As I have said before, successful investing requires the fortitude to not only have conviction about investing ideas but also the confidence to put them into action. Extraverts have the confidence to act decisively. They generally take the time to understand investment opportunities and examine the details of what they invest in. Lastly, they understand that accumulating wealth is about accepting risk; not all investors grasp the significance of taking risk. This is not to say that extraverts are overjoyed when things don't work out; rather, they typically understand that not every decision is going to work out well.

The downside to extraverts relates mainly to biases that concern being too confident that things will go their way and believing that no matter what happens they can exert some level of control over investment outcomes. In reality, overconfidence often leads to poor investment results, either because these investors feel like they can outsmart the markets on a regular basis, or they trade too much. Similarly, believing that investing outcomes can be controlled is a fallacy; there is so much uncertainty about investing that investors who believe they can control outcomes are not accepting the reality of the situation. Extraverts also may have trouble controlling spending, may invest based on what they relate to in other parts of their lives, and be too optimistic in their investing endeavors.

Advising Extraverts Extraverts are often the most difficult clients to advise, particularly those who have experienced losses. Because they like to control or at least get deeply involved in the details of investment decision-making, extraverts tend to eschew advice that might keep their risk tolerance in check. They are emotionally charged and optimistic that their investments will do well, even if that optimism is irrational. Some extraverts need to be monitored for excess spending, which, when out of control, can inhibit performance of a long-term portfolio. Other extravert investors make investments that align with their worldview but may not be the best investments for the long term.

For advisors, a reasonable approach to dealing with these clients is to take a leadership role in the situation. If the advisor lets the extravert client dictate all the terms of the advisory engagement, he will always be at the mercy of the client's decision-making process, which at times can be emotionally driven--and the result will likely be an unhappy client and an unhappy advisor. Advisors to extraverts need to also demonstrate the impact that financial decisions have on family members, lifestyle, or the family legacy. If these advisors can demonstrate to the client that they have the ability help the client make sound long-term decisions, they will likely see their extravert clients fall into step and be easier to advise.

Michael M. Pompian, CFA, CAIA, CFP is an investment advisor to family office clients and is based in St. Louis. His book, Behavioral Finance and Wealth Management, is helping thousands of financial advisors and investors build better portfolios of investments. Contact him at michael@sunpointeinvestments.com.

The author is a freelance contributor to Morningstar.com. The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect the views of Morningstar.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6NPXWNF2RNA7ZGPY5VF7JT4YC4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RYIQ2SKRKNCENPDOV5MK5TH5NY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)