Assessing the Merits of Less-Transparent ETPs

Are these new ETP formats a better mousetrap? Or a solution in search of a problem?

Exchange-traded funds have been a disruptive force within the asset management industry. ETFs have succeeded because they are--in many cases, though not all--a better way to package, distribute, and consume a variety of investment strategies. ETFs tend to be less costly and more tax-efficient versus traditional open-end mutual funds. They are also more widely available (given that they trade on an exchange, like stocks) and more readily accessible (given that investors can buy them in amounts as small as a single share on their own).

ETFs' gains have often come at others' expense. Most notably, many sponsors of traditional actively managed mutual funds have been suffering outflows for years. Some of the factors behind their woes are specific to the strategies they ply. Many active stock-pickers in the large-cap growth Morningstar Category (which has been the epicenter of outflows) have simply failed to deliver. But even many successful funds have hemorrhaged assets.

Another factor explaining active mutual funds' woes has been a matter of structure. ETFs' more tax-friendly profile has become even more appealing when framed against the waves of taxable gains that have been emanating from active funds in recent years.

Also, ETFs' broad availability and ready portability have made them the format of choice for many independent advisors.

Active fund franchises are not sitting idly by in hopes that this storm will subside. Many have entered the ETF arena, launching active ETFs, strategic-beta ones, more-vanilla cap-weighted fare, or participating across all three categories. But some holdouts are still shy. The key sticking point for many of them is daily transparency. Actively managed ETFs are required to disclose their full portfolio every day to ensure that market makers can quote accurate prices for the funds in the secondary market and keep their bid-ask spreads tight. Few active managers--especially those at the helm of stock portfolios--are comfortable with the idea of being the player at the poker table with their hand on full display.

This requirement has created an opportunity for firms looking to develop new exchange-traded product formats that attempt to serve up ETFs' most appealing features but without the need for daily transparency. These are commonly referred to as "nontransparent ETFs," though this is a misnomer in two respects. First, these products are subject to the same disclosure requirements as traditional mutual funds. So while they're less transparent than fully transparent active ETFs, they are every bit as transparent as other funds. Second, they're not all ETFs. Thus, "less-transparent exchange-traded products" is a more appropriate name--though I doubt it will catch on.

While a number of different formats for such products have been submitted to the SEC for review, just two have passed muster: Eaton Vance's NextShares and Precidian's ActiveShares. Today, there are a small number of products available in the NextShares format, and no ActiveShares products have been launched. Here, I'll take a closer look at how these and other formats of less-transparent ETPs stack up versus actively managed mutual funds and fully transparent actively managed ETFs. Are they a better mousetrap, offering meaningful benefits for investors? Or are they a solution in search of a problem?

How Do Less-Transparent ETPs Stack Up?

Fees Low costs are a trademark of ETFs. Low fees are made possible by lower manufacturing, recordkeeping, and distribution costs.

Most ETFs track indexes. Index-licensing fees tend to be these funds' largest expense. Index-tracking funds don't have to pay teams of portfolio managers and analysts to scour the earth for attractive investment opportunities. They just cut a check to an index provider for a rule book and regular updates on what to buy, sell, or hold. Thus, manufacturing costs are low.

Active ETFs, however, are a different story. They need teams of sharp analysts and portfolio managers and must equip them with the tools they need to do their job. As such, their manufacturing costs are relatively greater, which is reflected in their relatively higher fees versus their index-tracking peers.

ETFs also have lower recordkeeping costs, as they don't maintain accounts for individual shareholders. As such, their transfer-agency costs (the money funds pay to third parties to keep tabs on their shareholders) are lower relative to open-end mutual funds.

Also, most ETFs don't have embedded marketing and distribution costs in the form of 12b-1 fees. That said, it is important to note that pay-to-play arrangements have become more common in the ETF space in recent years. However, the rake is much smaller than it is in the case of mutual funds that pay a premium for eye-level shelf space in major distribution outlets. The most prominent example of this phenomenon is the proliferation of commission-free ETF platforms. In these cases, the payments made by ETF providers aren't passed directly to their shareholders, but they can be thought of as effectively placing a floor under these funds' fees.

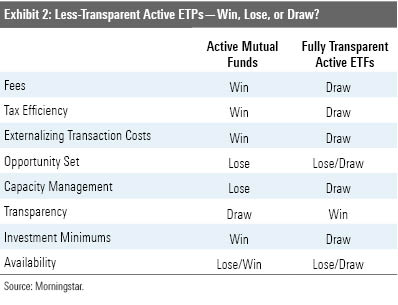

So, where do less-transparent ETPs stack up with respect to fees? Generally, they win versus traditional mutual funds, given that they don't levy 12b-1 fees and their transfer-agency costs are likely to be lower. However, these same features apply to fully transparent active ETFs, so it's a draw versus the incumbents.

Tax Efficiency ETFs tend to be more tax-efficient than mutual funds. This can be mostly attributed to their more regular use of in-kind redemptions. Sending securities out of a portfolio intact allows fund managers to avoid unlocking embedded taxable gains in the course of meeting redemption requests from departing shareholders. While all funds can meet redemption requests in-kind, it is uncommon for traditional open-end funds to do so. For ETFs, it is the normal course of business.

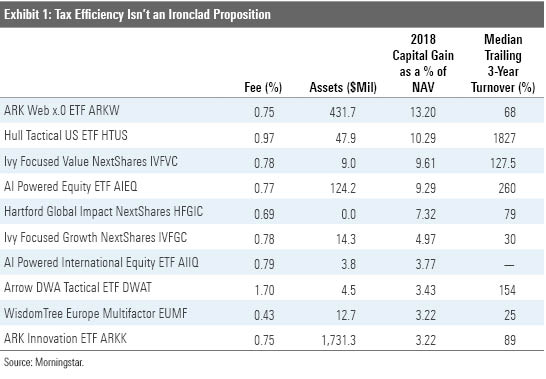

As it pertains to tax efficiency, fully transparent active ETFs and less-transparent ETPs both have a leg up over active mutual funds. That said, their ability to leverage their structural advantage depends in part on external factors. Most notably, these funds will need regular two-way cash flows in order to effectively purge securities with low cost bases from their portfolios--that is, consistent, and somewhat balanced, inflows and outflows. To date, that hasn't always been the case for many fully transparent and less-transparent active ETPs, especially those with high levels of turnover. Exhibit 1 below shows that these products' tax efficiency is not an ironclad proposition. While most actively managed ETPs don't regularly distribute taxable gains and all of them have the potential to be far more tax-efficient versus mutual funds (which I'll count as a win), there remains the potential for taxable capital gains distributions. So, when comparing fully transparent ETFs versus less-transparent ETPs on the basis of tax efficiency, it is a draw.

Externalizing Costs Portfolio transaction costs aren't directly measurable but can be a significant drag on funds' performance. The buying and selling of securities, whether prompted by managers' discretion or investors regularly entering and leaving the fund, comes at a cost.

That cost has a few different components:

1) There is the frictional cost of portfolio turnover, which comprises things like brokerage commissions, bid-ask spreads, and market impact--where trades move market prices away from the manager.

2) There is the opportunity cost of holding cash to meet regular redemptions.

3) Taxable capital gains distributions are also a meaningful part of this cost equation. As funds liquidate securities to meet redemptions or to free up cash to invest in new securities, they will often realize sizable taxable capital gains, which are passed on to shareholders.

In the case of open-end mutual funds, these costs are borne by ongoing shareholders. In the case of ETFs, transaction costs tend to be externalized. Rather than being socialized across existing shareholders, they are incurred by investors as they buy and sell ETF shares in the secondary market. The opportunity cost of holding cash is usually a nonfactor, as ETFs don't need to hold cash to meet redemptions. And, as discussed above, in-kind redemption makes ETFs generally more tax-efficient versus open-end mutual funds.

When it comes to externalizing real (commissions) and implicit (cash drag) costs, less-transparent ETPs are winners against open-end mutual funds. However, they are on level footing with fully transparent active ETFs on this front--it is a draw between the two.

Opportunity Set The investment opportunity set for both fully transparent ETFs and less-transparent ETPs is limited as compared with traditional open-end mutual funds. In both cases, limitations on the use of derivatives and the inability to invest in private placements limit managers' ability to showcase their best ideas in an exchange-traded format. The ActiveShares format is more restrictive still, as it is only allowed to invest in securities that trade contemporaneously with the products themselves (that is, during U.S. trading hours). Thus, managers' selection universe is limited to U.S. stocks, U.S. Treasuries, American depositary receipts, global depositary receipts, and U.S.-listed ETFs.

Broadly speaking, I view limiting managers' palette versus open-end mutual funds as a loss for both fully transparent active ETFs and less-transparent ETPs. The verdict is mixed for NextShares and ActiveShares as compared with fully transparent active ETFs. NextShares doesn't face the same limitations that ActiveShares does, so they finish in a draw with fully transparent active ETFs. I chalk up ActiveShares' strict limitations on its investable universe as a loss against fully transparent active ETFs.

Capacity Management Many of the best active managers know when adding more assets from new investors might be detrimental to their performance. While closing a fund when investors are flocking can be a difficult decision from a business perspective, it's done with fund investors' best interests in mind. This important capability is lacking in the case of all actively managed ETPs. From investors' point of view, I believe that this is a loss versus traditional open-end funds. As neither fully transparent ETFs nor less-transparent ETPs have the ability to turn away new investors, it is a draw between the two.

Transparency I believe that the daily transparency of most ETFs' portfolios is generally overrated. Few investors care to know what's in their funds' portfolios on a day-to-day basis. That said, that information is invaluable to the market makers that are tasked with quoting accurate prices and tight bid-ask spreads for these funds.

Less-transparent ETPs either trade via novel means (NextShares trades at a spread to end-of-day net asset value) or otherwise will/would provide less information regarding the makeup of their portfolios to fewer market participants on any given day. This was long a key sticking point for the SEC, which was rightly concerned that providing less information to the market would result in less accurate price quotes and wider and more volatile spreads. After all, if market makers don't have a good handle on what they're quoting prices for, they're taking bigger risks and would expect to get paid more for taking them. Though ActiveShares takes measures to allay these concerns, it remains to be seen whether funds using this format will be priced as efficiently and have comparable spreads to fully transparent active ETFs.

An ETP format that wouldn't mandate daily portfolio disclosure appeals to many active managers. This would--in theory--allow them to ward off potential front-runners and copycats. To the extent that there are market participants that would care to front-run these managers' trades or mimic their every move and that such activity would be detrimental to returns, less transparency could be beneficial to shareholders. But the fact is that most managers are probably flattering themselves if they think that there are opportunists lurking in the shadows looking to leach off their brilliance.

When it comes to transparency, less-transparent ETPs are in a draw with traditional open-end funds. The portfolio disclosure requirements are the same. Versus fully transparent active ETFs, less-transparent ETPs notch a win. But this win, in my opinion, is a victory for active managers worried about daily disclosure. We don't have enough data to say whether investors in these products will benefit from less frequent portfolio disclosure. My concern is that they may wind up losing a bit if bid-ask spreads do indeed wind up being wider and more volatile relative to fully transparent active ETFs.

Investment Minimums Investors can buy ETFs in an amount as low as a single share. This is substantially lower than the minimum investment requirement for most mutual funds--though investment minimums for some have been reduced to similarly low levels in recent years. As compared with most actively managed mutual funds, less-transparent ETPs notch a win with their single-share minimum investment. Versus fully transparent active ETFs, it is a draw.

Availability ETFs are broadly available to a large spectrum of investors given that they trade on an exchange, like stocks do. Anyone with a brokerage account can choose any fund off the ETF menu. Mutual fund distribution is far more fragmented. Depending on the channel in question, investors' choice is likely limited to a select subset of the full offering.

This is an area where less-transparent ETPs get a mixed report card. Owing to its novel trading mechanism, NextShares' distribution is limited. Only a small handful of platforms have made the necessary investment to allow their clients to access these products. Limited distribution has hampered this format’s growth. Precidian's ActiveShares and other formats still sitting with the SEC will (or would) trade on an exchange like conventional ETFs.

Given the different manner in which the pair of SEC-vetted less-transparent ETPs trade, it is a split decision on how these formats stack up with respect to availability. NextShares loses relative to both open-end mutual funds as well as fully transparent ETFs. ActiveShares is a winner versus mutual finds but finishes in a draw relative to fully transparent active ETFs.

Win, Lose, or Draw? Exhibit 2 below summarizes my assessment of how less-transparent ETPs stack up versus open-end mutual funds and fully transparent active ETFs. These new formats are a clear improvement over traditional open-end mutual funds in many respects. Their clearest advantages are their lower costs and the potential to be more tax-efficient. That said, it's not clear that they are an improvement over fully transparent actively managed ETFs--at least not from an investor's perspective. Their biggest win over fully transparent active ETFs is that they skirt the need to disclose their portfolios daily. In my mind, this is more a victory for asset managers than their investor clients. Ultimately, I'm not convinced that these formats are a better mousetrap for packaging and distributing active strategies than fully transparent active ETFs. In my opinion, these formats are a solution in search of a problem--one that's faced by product manufacturers.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/a90ba90e-1da2-48a4-98bf-a476620dbff0.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZHTKX3QAYCHPXKWRA6SEOUGCK4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/a90ba90e-1da2-48a4-98bf-a476620dbff0.jpg)