Will Your Retirement Get Whacked by the WEP?

A little-understood Social Security rule called the Windfall Elimination Provision can catch public-sector retirees off guard.

A friend called recently about her Social Security benefit, and she was not happy. Preparing to retire following a successful career in academic, private sector, and federal government positions, she expected to retire on a mix of Social Security, a pension, and savings.

Then she checked the amount of her projected Social Security benefit and was surprised to learn that she'd be getting roughly 40 percent less than the projection she had seen on the annual benefit statements she had received over the years. Could I explain what was going on?

Welcome to the WEP--the Windfall Elimination Provision, a little-understood Social Security rule designed to prevent double-dipping from Social Security and public-sector pensions. The WEP and its cousin, the Government Pension Offset, can mean very sharp benefit cuts.

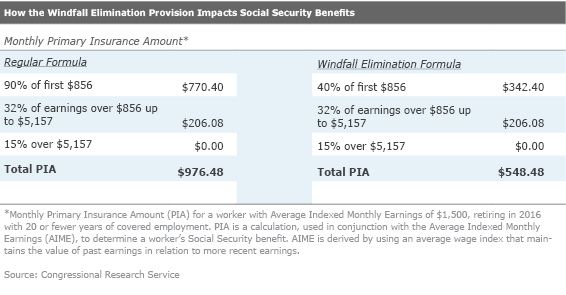

Under the WEP, a worker retiring this year who might otherwise receive a $976 monthly Social Security benefit could see that chopped to $548, according to the Congressional Research Service. The GPO can result in even sharper cuts to spousal and survivor benefits.

The WEP affected 1.7 million beneficiaries at the end of 2015, according to the Social Security Administration, while the GPO impacted about 652,000. The provisions impact many teachers, police, firefighters, postal workers, air traffic controllers, and some federal government state, county, local, and special district workers.

The WEP was enacted as part of broader Social Security measures taken in 1983 to avert a solvency crisis. The intention was to eliminate a supposed advantage in the Social Security benefit formula to people who also had pensions from jobs that are not covered by Social Security.

But the logic is inscrutable to all but policy analysts and actuaries. And the WEP's whack regularly generates outrage from retirees, who approach this with a very straightforward question: "If I earned the benefit, why am I not receiving it?" Employee associations representing affected state and municipal workers have been pushing for reform of the WEP for years. Legislation has been introduced repeatedly in both chambers of Congress that would repeal both the WEP and the GPO. That would be expensive; the SSA's chief actuary estimates that it would bring the depletion date for Social Security's trust fund one year closer; in 2007, the SSA estimated that repealing the WEP only would cost $40 billion over 10 years.

Several of the reform proposals also include changes to enforcement mechanisms to make sure that whatever reductions remain are spread evenly across all affected workers, since the current system is imperfect.

The Obama administration's fiscal 2017 budget included a reform proposal for both the WEP and the GPO. But the plan that seems to have traction takes an incremental approach and focuses on the WEP only.

The Equal Treatment of Public Servants Act of 2015--sponsored by Rep. Kevin Brady, R-Texas, who chairs the powerful Ways and Means Committee--was initially estimated to reduce the the WEP penalty by 43 percent. Under a revision that surfaced in July, a 15% reduction in the penalty would begin in 2018, and a 50% reduction in the WEP penalty would begin in 2027, according to estimates by the Social Security actuary. Had the proposal been in effect this year, the proposal would have helped about 1.25 million beneficiaries.

The bill has been hung up over debate among the sponsors and reform advocates on who exactly should receive relief and how to pay for it.

"It all adds up to how much savings are being created by certain portions of the bill and how the savings will be used to reform the WEP formula going forward or provide relief," says John Hatton, deputy legislative director for the National Active and Retired Federal Employees Association, one group that has lobbied to get rid of the WEP and the GPO. (The bill aims to be budget-neutral through 2025; a fact sheet on the current proposal can be found here.)

Why would government workers be treated differently from everyone else? The answer begins with the way that Social Security benefits are distributed across wage-earners with varying incomes.

Social Security's benefit formula is progressive; workers with low average lifetime earnings get a higher benefit amount compared with their earnings than people who are better paid. Social Security expresses your benefit as a primary insurance amount. This is derived by calculating your average indexed monthly earnings--your top 35 years of earnings before age 60 are indexed then to put them on more of a proper comparative basis with the earnings level in our society as of the year you turned 60. That is done using the average wage indexing series that the Social Security Administration computes every year.

Then, your primary insurance amount is calculated. This is a weighted formula that gives a higher benefit relative to career earnings for a lower earner than for a high earner. A worker receives 90% of average indexed monthly earnings for the first segment of PIA (also referred to as a "bend point".) This year, that covers the first $856 of monthly AIME. For the next segment, between $856 and $5,157, you get 32% of AIME. For any AIME amount above that amount, you get 15% of AIME.

But the PIA formula doesn't distinguish between workers who had low wages and those who worked for part of their careers in jobs not covered by Social Security. Many federal and state jobs are outside the system because they are covered by government pension plans.

The WEP aims to eliminate the high benefit return these workers get on their Social Security income when they are not really low-income. The Committee on Ways and Means offers this example. Consider two workers: one with her entire career as a privately employed security guard; the other splits her career between a privately employed security guard and a police officer for a government employer that does not participate in Social Security.

Throughout their careers, both have the same average monthly earnings--$4,000. That full amount is cranked into AIME for the private sector worker, but just $2,285 is considered for the worker who split her time between the public and private sectors. The WEP reduces initial Social Security payments from $1,776 to $800.

One cause for concern: some research indicates that the WEP is regressive--that is, it disproportionately affects low-income workers who most benefit from Social Security. The argument here is that the WEP adjustment affects only the first bracket of the benefit formula, causing a proportionately larger cut to workers with lower AIMEs and benefit amounts.

The impact of the WEP is reduced for workers who spend 21 to 29 years in Social Security-covered work, and it is eliminated entirely for those who spend 30 years or more in such jobs.

For federal employees, the WEP applies only to workers who started their federal employment before 1983, were covered by the Civil Service Retirement System, and did not contribute to Social Security.

The provision does not apply to people covered by the newer Federal Employees Retirement System, which is a defined contribution plan. Those workers contribute to Social Security.

The cuts can come as a surprise when workers file for benefits. Until 2005, no law required employers to tell workers they were affected. Even now, they must only inform new workers of the possible impact on Social Security benefits earned in other jobs.

The annual statement of benefits issued by the Social Security Administration has included a description of the possible impact of the WEP and the GPO since 2007; for workers who are affected, the statement includes a link to an online tool to help them calculate the impact.

People who have worked only in jobs not covered by Social Security get a letter indicating that they are not eligible.

For more on the WEP and GPO, consult this resource page on the Social Security Administration website.

Mark Miller is a retirement columnist and author of The Hard Times Guide to Retirement Security: Practical Strategies for Money, Work, and Living. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.com.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)