Will the Election Impact Healthcare Earnings?

How Morningstar healthcare stock analysts size up the effect of potential legislative proposals.

Morningstar analysts don’t have a crystal ball, so they don’t waste a lot of energy on trying to predict whether a Republican or Democrat will occupy the Oval Office this time next year.

That said, our healthcare analysts keep a close eye on what Congress is doing when it comes to potential legislation. Indeed, if there is one sector whose fortunes will be greatly altered by how Americans vote, it is healthcare. Republicans have talked about repealing the Affordable Care Act, and Democrats have discussed how to control the escalating prices of drugs, among other topics.

Morningstar senior analyst Karen Andersen recently looked at several proposals making the rounds on Capitol Hill. While these proposals are favored by Democrats and are unlikely to garner any support in the current Congress, that outlook could change depending on this year's election cycle. Andersen isn't forecasting the outcomes of certain races, but she and her colleagues try to anticipate the impact on the earnings of some companies if these proposals did become law.

Rob Wherry: Your research doesn't entail you making a call about whether Donald Trump or Ted Cruz or Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders is in the White House, right?

Andersen: We're agnostic about the White House. We did look at Congress and how difficult it would be for Democrats to gain the 30 seats they need to get control of the House. But we're not really commenting on which way public opinion is going to swing come November.

The talking heads who wax on about the impacts down ticket if one or the other candidate wins, is that all noise to you? How do you process such information?

Andersen: It's difficult, especially in a sector like healthcare, where we do have from time to time pretty significant reforms go through, such as the Affordable Care Act. But, in the case of this research, we focused on the plans from the Democrats. Just because on the Republican side, they have suggested some ideas for reform, but most of those proposals really wouldn't have any kind of adverse impact on drug companies--they may even help them. Some ideas could even help accelerate the time to market.

What we're really focused on is the risk that the Democrats have the White House and take control of the House and Senate. If that happens, we could start to see some of these bills that have been floating around and haven't been able to get bipartisan support actually get passed. We took a look at what those bills would be, and for the most likely ones, we tried to quantify the impact on the companies we cover.

How many bills are you monitoring?

Andersen: Seven.

Some of those are long shots, right, even if the Democrats regain control of Congress?

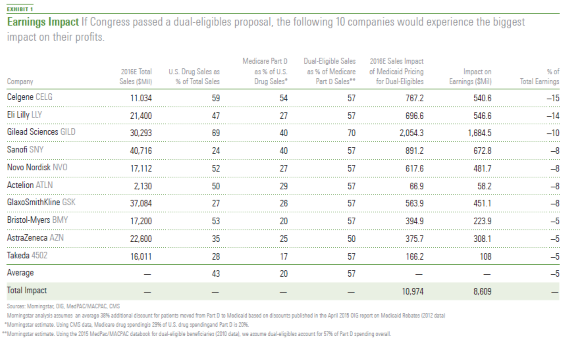

Andersen: I'd say the dual-eligibles proposal is the biggest threat. Democrats support it, but given the fact that it's more about returning to a status quo and that it would allow pretty significant cost savings and be pretty easy to implement, it looks like an appealing way to control costs even if you are a Republican.

Dual-eligibles are the people who qualify for both Medicaid and Medicare. They tend to have lower incomes and are in poorer health, correct?

Andersen: There are patients who were covered for their drug benefits under Medicaid. But under the prescription drug benefit in Medicare, there are some patients who were pulled into that program, patients who were also eligible for Medicaid. That's why they're called dual-eligibles.

It accounts for--depending on how you define dual-eligible--about 30% of the patients who are covered in Part D, the prescription drug benefit for Medicare. But they do make up a significantly higher percentage of the costs of the care. So, yes, they do tend to be lower income and, particularly in drug spending, tend to have higher prescription drug costs.

The controversial part is if they shift over, they can get cheaper drugs?

Andersen: It basically boils down to how drugs are reimbursed by Medicare versus Medicaid. In Medicaid, there are mandatory rebates, and drug companies are very limited in the amount of price increases they can take every year. With Medicare, the programs for drugs are actually run by private payers, so the prices are negotiated.

The prices do typically increase more year to year, but there is no mandatory rebate. We've done some research on this subject and the Medicaid rebate is significantly steeper for a lot of drugs than it is in Medicare.

You assigned a 30% probability to that proposal being passed?

Andersen: Yes, 30% over the next four years.

What's the impact on the industry?

Andersen: About $12 billion a year in revenue that could be lost over the next decade.

There's a range out there of between $103 billion and $123 billion over the next decade.

Andersen: That's the estimates given by the Congressional Budget Office. But we came up with our own figure of $12 billion.

Would it hit some companies harder than others?

Andersen: Yes. You have to break this out, especially when it comes to the dual-eligible patients. First of all, you have to think about which drug companies have a lot of exposure to the United States. That's the first step. Next, you need to think about what percentage of their U.S. sales are tied to Medicare--the Medicare prescription drug benefit. A lot of companies have higher sales of biologics--these are the drugs where you might have to go into the hospital to have something administered. That's not covered under this program. Or a company might have drugs that serve patients that tend to be younger, so they wouldn't be in Medicare yet. We looked at that.

Then, you need to look at dual-eligibles as a percentage of the Medicare prescription drug benefit. There are some markets where a very high percentage of its Medicare patients are also dual-eligible--for example,

You also looked at a proposal that would allow the government to negotiate prices on behalf of consumers directly with drug companies.

Andersen: Negotiating pricing in Medicare, that's something that's just been in the news so much we thought it was important to analyze what would happen if something like that did get through.

Ever since the prescription drug benefit in Medicare went through, the government has been forbidden from negotiating pricing. It has always been an appealing idea for helping to control prices, just given the fact that Medicare does account for--I think it's around 30% of drug costs today--it would have significant leverage over the drug companies when it comes to negotiating.

There are a few things that are holding this back. First of all, what we've talked about isn't a bipartisan idea. This is something that's typically been favored by Democrats. So, there would need to be more unified government. Even if you had that, when you look at the kind of negotiating leverage the government would have with that market share, it doesn't really differ that much from the market shares we already see from private payers. There's actually already been a lot of pricing pressure, a lot of consolidation among pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs. The biggest PBMs have market shares that are pretty close to 30%--

You also researched drug importation. Is that people going to Canada, for example, and bringing back drugs to save money?

Andersen: The basic idea is that drugs in other countries can be significantly cheaper, so why don't we help Americans save money and allow them to buy drugs and bring them back to the United States? We have actually seen laws passed a couple of times allowing this, but it never gets to the point of becoming legal because there's a hurdle for Health and Human Services. That agency has to prove that there isn't a significant safety risk and that the benefits outweigh the risks. There are always fears of having some kind of counterfeit drugs.

Then, there are the cost savings, too. On that side, it seems like it would be a great way to save money. But then you start thinking about all the loopholes and the ways the drug companies can get around this. For example, they could label drugs specifically for certain markets, or if drug companies know that certain countries are selling back to the United States, they'd raise their prices there or limit supply. There are all sorts of ways that could reduce the savings, but you would still have that safety risk lingering out there.

Do the concerns you mention factor in to how you and your colleagues calculate economic moats and price targets?

Andersen: Moats for drug companies are mostly tied to their intangible assets--their ability to innovate and come up with products where they can have strong pricing power with limited competition. So, multiple products driving their profits. And they diversify as well.

If a proposal such as dual-eligible goes into effect, I wouldn't foresee a moat change, even for the companies that are hardest hit. Most of these companies either have enough products that they sell internationally that could make up for the lost revenue or enough products in the pipeline, where they can adjust for any kind of pricing impact they see now. When they start to launch more innovative products over the next few years, they can charge higher prices and make up for it in other ways.

Some of the other proposals you mentioned in your research seem to be centered on drug pricing. Is that the argument that will dominate the debate in the next few years?

Andersen: The government wants to encourage innovation and wants to see more effective drugs out there to treat all sorts of diseases. In general, they don't want just pure price controls. I'd say most politicians wouldn't be in favor of mandating Medicaid rebates for everyone or the more severe measures like that.

But they also are very aware that drug prices have been increasing quite a bit. Last year, pricing really accelerated. A lot of that was because of hepatitis C and the launch of an expensive new therapy. Drug companies have been steadily increasing prices on drugs over the years, even ones that have been on the market for five or 10 years already. In the future, the government is going to have to walk this line of encouraging innovation, but trying to make sure that the increases in spending that they're seeing on drugs are going to supporting the right therapies.

Let's talk about the Affordable Care Act. Republican presidential candidates have vowed to repeal the law if they win the White House. Have you and your colleagues had discussions about such a scenario?

Andersen: At this point, our assumption is that it would just be too difficult to unravel that law. We're too far down that road.

To wrap things up, if readers are considering an investment in the healthcare sector, what are the risks they should keep in mind?

Andersen: Some of the steps we took doing our dual-eligible analysis apply to any kind of risk you might be looking at for healthcare stocks. First of all, how globalized is the company? Is it very reliant on the United States for its sales and its profits? And then beyond that, definitely continue looking at patent exposure, but also maybe start looking at what percentage of sales come from biologic therapies instead of these more traditional small molecules--the pills that people take. Having diversification is important.

We are also very focused on what can the government do to control drug prices, and what do we think is most likely to happen to the drug stocks because of it? But the whole other issue that we've been dealing with is more on the private side, where there has been a lot of consolidation with payers. They are negotiating more aggressively with the drug companies. Drug companies are a little bit more hesitant to take bigger price increases today than they were a few months ago. So, even if we don't see any pressure from the government, I think there's some real pressure on future price increases for drugs that are in very high-profile markets or ones that are seeing a lot of competition. I think companies don't want to be in the spotlight. If they highlight their growth, they don't want that growth to be driven purely from price increases.

This article originally appeared in the April/May 2016 issue of Morningstar magazine. To subscribe, please call 1-800-384-4000.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/558ccc7b-2d37-4a8c-babf-feca8e10da32.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ECVXZPYGAJEWHOXQMUK6RKDJOM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/KOTZFI3SBBGOVJJVPI7NWAPW4E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/V33GR4AWKNF5XACS3HZ356QWCM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/558ccc7b-2d37-4a8c-babf-feca8e10da32.jpg)