The Trouble With Social Security COLAs and Medicare Premiums

Meager cost-of-living adjustments coupled with Part B increases continue to erode the standard of living for many retirees.

It's become an annual two-part reminder of the bite that healthcare costs can take in retirement.

In October, Social Security announces the cost-of-living adjustment, or COLA, for the year to come. About one month later, Medicare follows up, posting the new monthly standard Medicare Part B premium.

If you're enrolled in both programs, you don't know your net COLA until both numbers are unveiled, since the Part B premium is deducted from your Social Security benefit. Inevitably, some portion of the COLA is gobbled up by higher Part B costs--and the bite can be significant, since the Medicare premium generally rises at a rate several times higher than the COLA.

Last month, Social Security announced a 1.3% COLA for 2021. That's pretty meager, and it fits the pattern over the past decade, a time when the COLA has averaged just 1.6%. But it is what it is. The COLA is determined automatically, pegged to the change in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers, or CPI-W, in the third quarter compared with the previous year.

On Nov. 6, Medicare announced that the monthly Part B premium will rise by $3.90 to $148.50 in the new year. The increase actually was on track to be much larger, but a coronavirus relief measure passed by Congress capped the increase at 25% of whatever it would have been if Medicare had followed its usual formula.

The COLA is one of the most valuable features of Social Security. But this year's numbers serve as a reminder that the ongoing low-COLA climate erodes the standard of living for many seniors. The formula needs to be revisited, and other changes to the benefit structure also could help.

How the COLA Works By federal law, the dollar amount of the Medicare Part B premium increase cannot exceed the dollar amount of the COLA--a "hold harmless" feature that ensures net Social Security benefits do not fall.

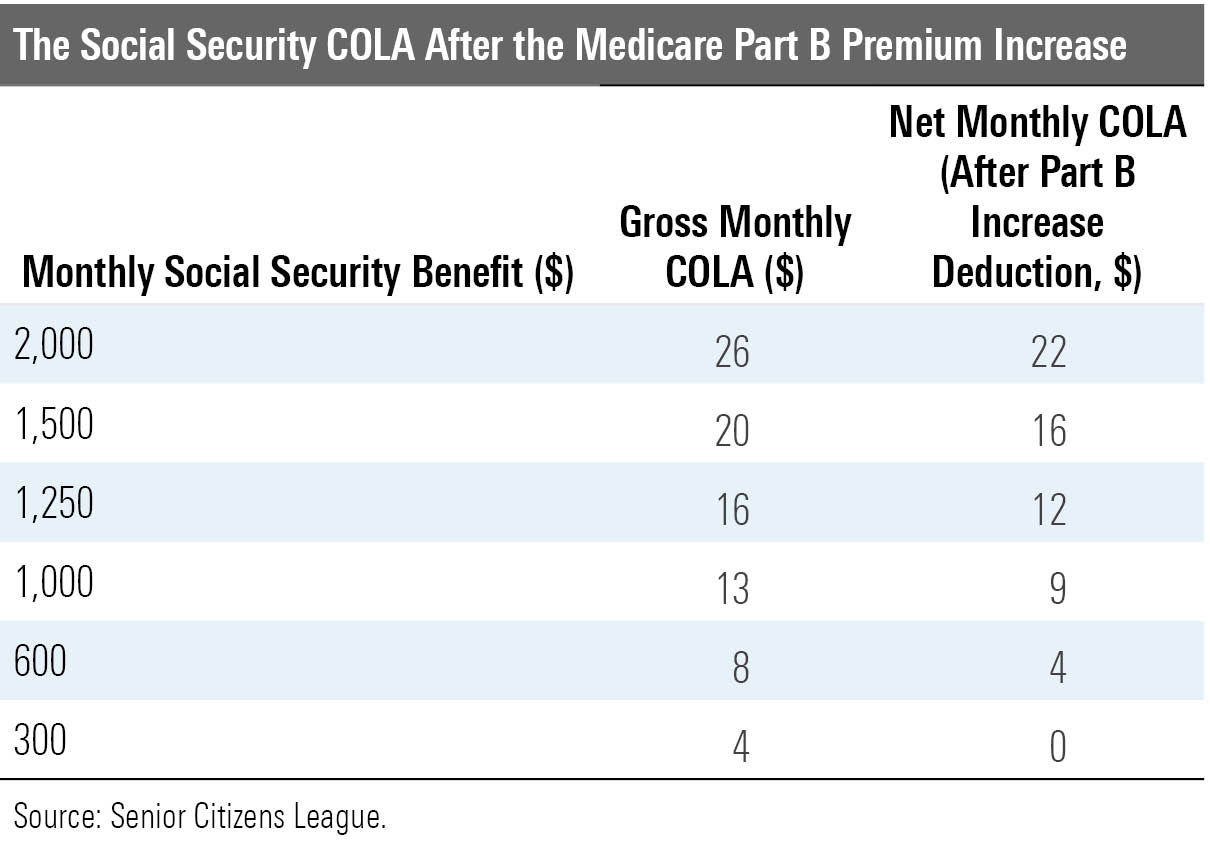

For people with high benefit amounts, next year's Part B premium will shave off a few dollars from the dollar increase. For people with low benefit amounts, however, Medicare eats up most or all of the COLA; in cases where the dollar amount of the Part B hike would be larger than the COLA (also in dollars), the Social Security benefit is unchanged owing to the "hold harmless" provision.

The table below shows how the numbers will work next year for people receiving various benefit amounts.

Seventy percent of the Medicare population is enrolled in both programs, and that's the group affected by this math. Those not held harmless include anyone delaying filing for Social Security benefits; affluent seniors who pay high-income Medicare premium surcharges also are not protected. Some federal and state government retirees don't receive Social Security, so they pay whatever the going rate is for Part B.

The Reform Landscape The low-COLA environment over the past decade is unprecedented, notes Mary Johnson, Social Security and Medicare policy analyst for The Senior Citizens League.

"A decade represents a significant portion of the time a person spends in retirement, so it has a real impact on the lifetime retirement benefits you receive from Social Security," she notes.

An erosion of living standards impacts low- and moderate-income retirees most, since they usually rely heavily on Social Security income. But it's even a concern for people who have amassed significant retirement savings. How so? Because of longevity risk--that is, living to a very advanced age and exhausting savings. At that point, Social Security income becomes even more critical.

Ideas for Reform Most moderate-to-progressive Social Security reform plans floated in recent years call for improving the COLA by changing the formula used to determine annual increases. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics maintains an experimental alternate index, the CPI-E (for elderly), that aims to measure the types of goods and services most relevant to seniors. It is based on spending by adults aged 62 and older and their families, and it assigns greater weight to healthcare spending. The CPI-E would increase the COLA by an additional 0.2 percentage points annually, according to Social Security's actuaries.

That may not sound like much, but it becomes significant over time as the COLAs compound, notes Richard W. Johnson, director of the program on retirement policy at the Urban Institute.

"Over 20 or 30 years, it does add up," he says. However, he adds, the CPI-E is no panacea. "It won't always increase faster than other inflation measures--for example, if healthcare costs fall. But generally, this index will grow faster than the current index."

Other ideas have been proposed that would address the standard-of-living question, all on the Democratic side of the political aisle. One oft-mentioned approach would boost Social Security benefits for caregivers, recognizing that caregiving duties can depress benefits by cutting into working hours and wages. That could be done by allowing caregivers to exclude some nonworking years from the calculation of their benefits; another is to provide a wage credit to caregivers.

President-elect Joe Biden's Social Security plan would provide a bonus for long-term recipients of Social Security, equal to 5% of the average benefit to beneficiaries who had collected payments for 20 years. This would phase in, beginning with a 1% boost for beneficiaries who had collected for 16 years.

Another idea is to increase benefits for surviving spouses. When a spouse dies and benefits stop, the surviving spouse can lose as much as half of the household's retirement income. The current survivor benefit is equal to 100% of the deceased spouse's benefit, but that doesn't help much in cases where both spouses had similar wage histories and benefits.

Biden's plan, for example, would allow survivors to collect 75% of the total benefit received by the household before their deceased spouse died, as long as the new payment does not exceed the benefit received by a two-earner couple with average career earnings.

The cap means this change would help mainly moderate and low-income beneficiaries, says Johnson.

"That's important, because poverty rates are still quite high for widows, so this is something that would help a very vulnerable group," he notes.

For more, listen to my recent podcast interview with The Senior Citizens League's Mary Johnson about the COLA.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to WealthManagement.com and AARP The Magazine. He publishes a weekly newsletter on news and trends in the field at RetirementRevised. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the views of Morningstar.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)