Traditional Investments Can Weather Inflation

Traditional stock and bond portfolios will likely grow purchasing power over the long term better than instruments commonly used as inflation hedges.

A version of this article previously appeared in the October issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Click here to download a complementary copy.

Inflation hasn’t been a problem in the United States for a long time. But given the Federal Reserve’s aggressive monetary policy and large government deficits, which have pumped trillions of newly minted dollars into the U.S. economy since 2008, many investors are worried inflation may soon make a comeback. While there are steps you can take to mitigate the impact of inflation on your portfolio, the best solutions are probably the simplest.

Growing Money Supply The U.S. money supply has grown 7.4% annually since the end of 2007, when the Fed embarked on a series of rate cuts and significantly expanded its balance sheet to stimulate the economy during the global financial crisis. Federal deficit spending also contributed to this growth.

This money supply expansion is up from the 5.9% annual growth rate from the end of November 1980 through 2007. The difference may not seem like much, but the U.S. economy has grown more slowly in the post-crisis period, which suggests the growth in money supply should be more inflationary, as there are more dollars chasing fewer goods and services.

Yet inflation has been remarkably low, averaging just 1.64% from the end of 2007 through August 2020. How can the Fed get away with flooding the economy with newly minted money without suffering the effects of inflation?

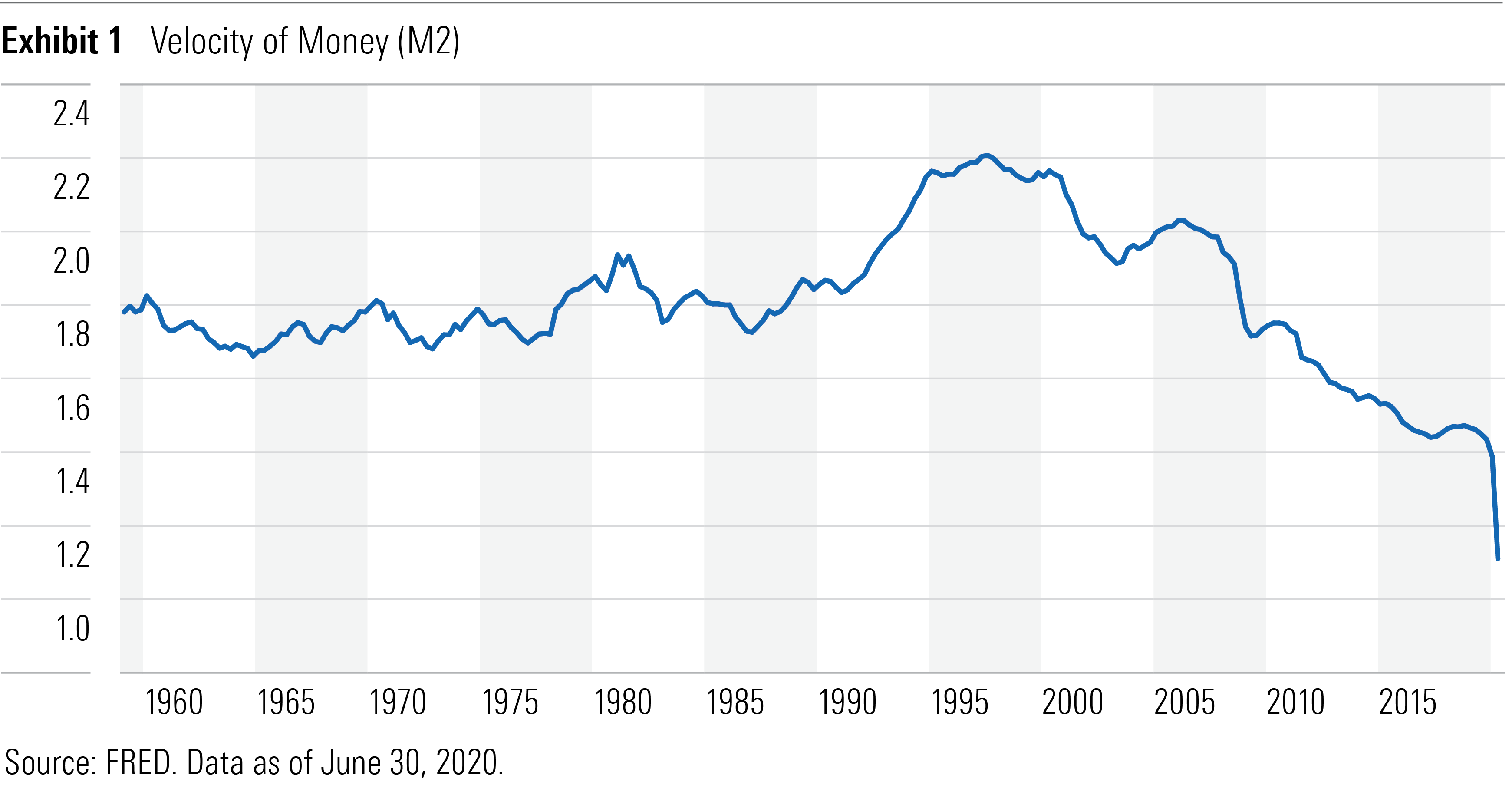

As the money supply has grown, the Fed’s actions have had a diminishing effect. Exhibit 1 shows the rate at which people have been spending each dollar has been declining. Central banks can print money all day, but if there’s still excess production capacity in the system or consumers balk at price increases, inflation will remain low.

There are other reasons inflation has remained under wraps. For example, it’s easier than ever to compare prices online for consumer products, which contributes to price competition and low inflation. But more importantly, inflation expectations are largely self-fulfilling. Inflation has been so low for so long that the public has come to expect it, and producers and employees have adapted accordingly. The Fed has been instrumental in fostering these expectations by establishing a credible policy of raising rates to stymie inflation. However, it has recently signaled its desire to increase inflation expectations.

Inflation May Be Higher in the Future Low inflation may not seem like a problem, but it contributes to low interest rates. When rates and inflation are low, as they are today, it limits central banks' ability to stimulate the economy, as the experience of Japan over the past 30 years illustrates.

To raise inflation expectations, the Fed adopted an “average inflation targeting” policy in August 2020. Under this new approach, it will allow inflation to run above its 2% target following periods when it has been below that threshold (as it has for much of the past decade). That marks a departure from the previous approach, where the Fed would have been more inclined to raise rates faster to prevent inflation. This shift will likely modestly increase inflation over the next few years.

Investment Implications Inflation alone shouldn't be a significant problem for broadly diversified portfolios, particularly if it is expected, as prices adjust to accommodate the expected impact on purchasing power. However, long-term fixed-rate bonds and cash in low-interest-bearing accounts are more susceptible to inflation than stocks and shorter-term bonds.

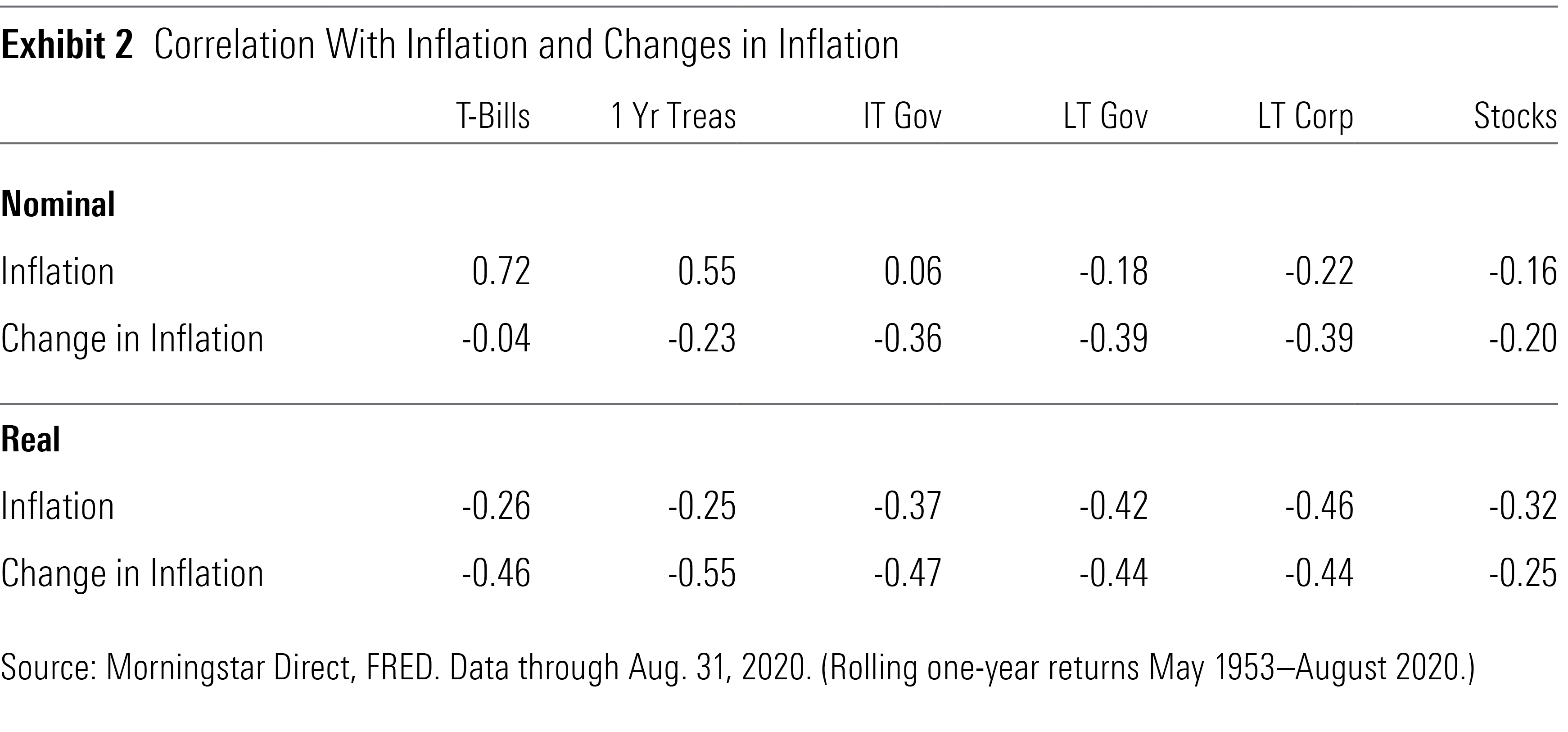

It’s easy to understand how inflation can be a negative for fixed-rate bonds, where there’s no growth to offset the erosion in purchasing power. The link is less clear for stocks. While stocks’ cash flows aren’t fixed and they can often pass some of their rising costs to customers, inflation can still hurt profitability, particularly in the short term. Yet historically the nominal (non-inflation-adjusted) returns on stocks and intermediate- to long-term bonds have had fairly low correlations with inflation, as shown in Exhibit 2.

Short-term government bonds tended to fare better than their longer-term counterparts during periods of inflation. That’s not surprising. Bond prices incorporate inflation expectations over the remainder of their lives. When inflation moves higher, so do investors’ expectations for future inflation. Accordingly, bond prices tend to move lower to compensate. However, shorter-term bonds’ prices don’t need to adjust as much, as they mature more quickly and are replaced with bonds issued with higher yields to maturity.

The picture looks less rosy when considering the relationship between performance and unexpected inflation, as proxied by the annual change in the inflation rate. Each asset group had a stronger negative correlation with unexpected inflation than with the absolute level of inflation. That’s because inflation that falls in line with expectations has already been reflected in market prices, so it shouldn’t move the needle that much. In contrast, inflation that the market doesn’t anticipate doesn’t affect prices until it happens. As before, longer-term bonds tended to fare worse when inflation exceeded expectations, but even short-term bonds weren’t immune.

Not surprisingly, each asset group’s real (inflation-adjusted) returns were more negatively correlated with both the absolute inflation rate and changes in the inflation rate than their nominal returns. That’s intuitive, as inflation directly reduces real returns.

But inflation doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Historically, it’s tended to spur interest-rate hikes, which could explain part of the apparent relationship between inflation and investment returns. If the Fed is more accommodating of inflation (leaving rates low while inflation ticks up), as it has signaled, higher inflation may be more benign for investments going forward than it has been in the past.

A regression analysis helps disentangle inflation and interest rates. The model I constructed explains each asset group’s rolling annual real returns as a function of the inflation rate and annual change in the 10-year Treasury yield.

Interest rates were more significant performance drivers than inflation for all bond groups. After controlling for interest rates, inflation had a modest negative impact on real returns for each of these groups (except one-year Treasuries, where the effect was insignificant). As before, longer-term bonds were more susceptible to inflation than shorter-term bonds.

Inflation appeared to have a stronger relationship on stocks’ real returns than interest rates. However, this model explained only about 10% of the variance in stock returns, which was considerably less than the corresponding values for the intermediate- and long-term bond groups. So, inflation isn’t high on the list of risks stock investors should be concerned about.

While inflation moderately hurts real returns for stocks and intermediate- and long-term bonds, these asset groups have had no problem outpacing inflation over the long term. That said, there aren’t many good short-term inflation hedges.

No Perfect Inflation Hedges Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities offer the most direct hedge against inflation, but even they aren't perfect. Their principal adjusts with changes in the Consumer Price Index. When consumer prices increase, so do their coupon payments, which are paid as a fixed percentage of the adjusted principal. Investors who buy TIPS when they are issued and hold them until maturity should receive a fixed real return, independent of inflation. However, things change when you hold TIPS in an index fund that trades them on the secondary market, where prices don't necessarily move in lockstep with inflation.

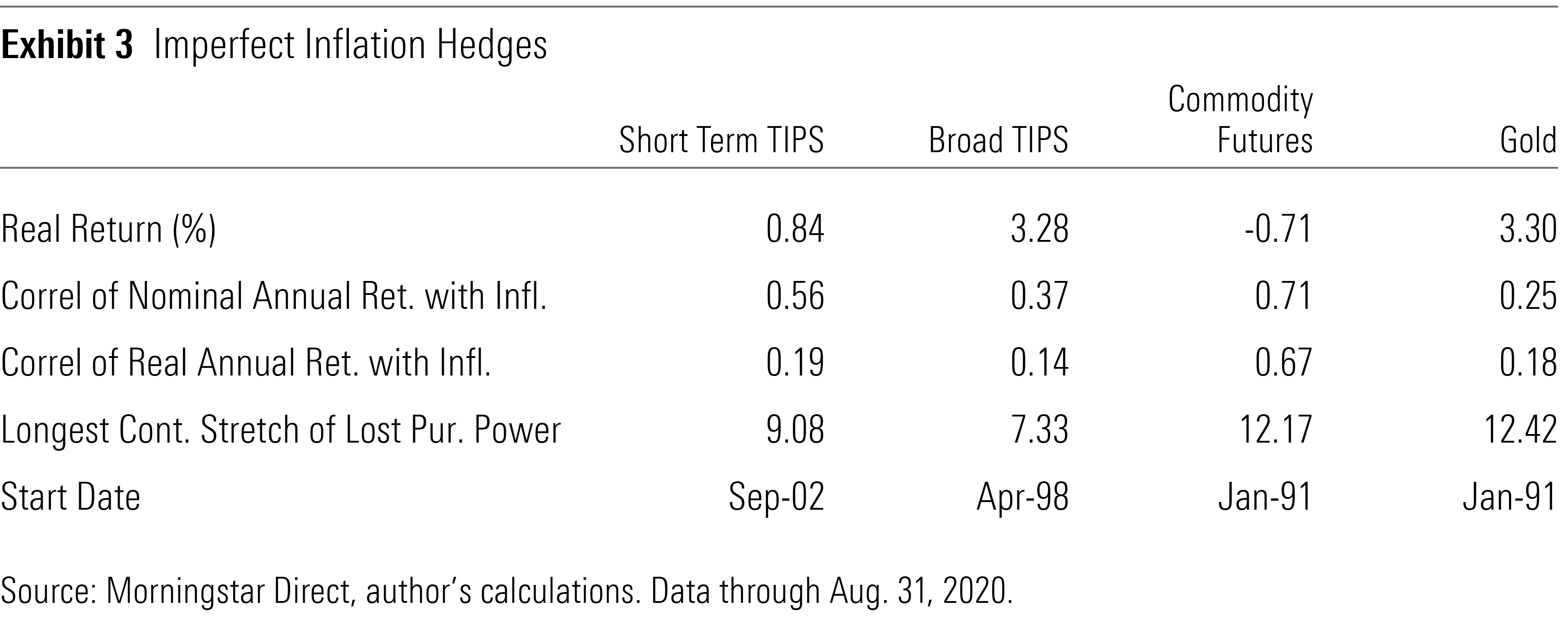

Exhibit 3 shows the correlations between returns and inflation for short-term and broad TIPS indexes, as well as commodity futures and gold, which are sometimes used as inflation hedges.

As expected, both TIPS indexes’ nominal returns are positively correlated with inflation, and that correlation is higher for short-term TIPS, which are less sensitive to long-term rate movements. However, there was a seven-year stretch when the broad TIPS index didn’t keep up with inflation. Despite its higher correlation with inflation, the short-term TIPS index experienced an even longer stretch of underperformance. To put those figures in perspective, the longest stretch during which the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index lost purchasing power since TIPS were introduced was less than three years.

Correlation with inflation isn’t everything. Real returns and time horizons matter more. For example, commodity futures are even more highly correlated with inflation than TIPS, but investors who held such a strategy from January 1991 through August 2020 would have lost purchasing power. Gold posted better real returns than the broad commodity futures index, but its link to inflation is more tenuous, and it experienced a stretch of more than 12 years during which it lost purchasing power.

Keep It Simple It's tough to completely protect against inflation in the short term, but that's OK because inflation usually isn't a big problem in the short term. Over the long term, the erosion of purchasing power can become significant.

The best option to manage this risk is probably the simplest: sticking to broad, market-value-weighted stock and bond portfolios, like Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF VTI, which has a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold, and Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF BND, which is rated Gold. Over the long term, these have tended to preserve and grow purchasing power better than instruments commonly used as inflation hedges, like short-term TIPS, commodity futures, and gold.

TIPS are the most promising inflation hedge. However, their prices don’t move in lockstep with inflation, and broad TIPS indexes tend to carry greater interest-rate risk than BND. While short-term TIPS are safer on that front, they have more limited return potential, which may outweigh their benefits.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZHTKX3QAYCHPXKWRA6SEOUGCK4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/56fe790f-bc99-4dfe-ac84-e187d7f817af.jpg)