Investing with a high-conviction manager may sound prudent, as it can help increase investors’ exposure to managers’ strong ideas, which could potentially lead to better performance. But higher portfolio concentration may also increase the risk of missing out on some of the market’s other big winners, which have historically driven a disproportionate share of its returns.

A recent study from Morningstar Research Services showed that, in practice, these opposing forces tend to balance each other out, so there isn’t a significant relationship between portfolio concentration and gross returns among U.S. equity mutual funds. Yet, concentrated managers tend to charge more, and the risk of manager selection is greater for these funds because of the wider range of potential returns between winners and losers.

Below, see some of the key findings from this study.

How our research evaluated portfolio concentration

This study measured the potential relationship between portfolio concentration and performance by grouping actively managed funds in each Morningstar category into quartiles based on the percentage of assets they invested in their top 10 holdings at the end of each year. It then tracked the gross returns (which controls for differences in fees) of each group over the next 12 months before updating the group assignments. The analysis included non-surviving funds and used the original category assignments as of the sorting date.

To assess the odds of finding high-performing managers in each group, the study also calculated success rates for the funds in each quartile over both a 12-month holding period and a 36-month holding period. For this study, success rates were defined as the number of funds that survived and outperformed their respective category’s benchmark over each holding period, divided by the total number of funds as of the sorting date.

Greater portfolio concentration doesn’t necessarily improve performance

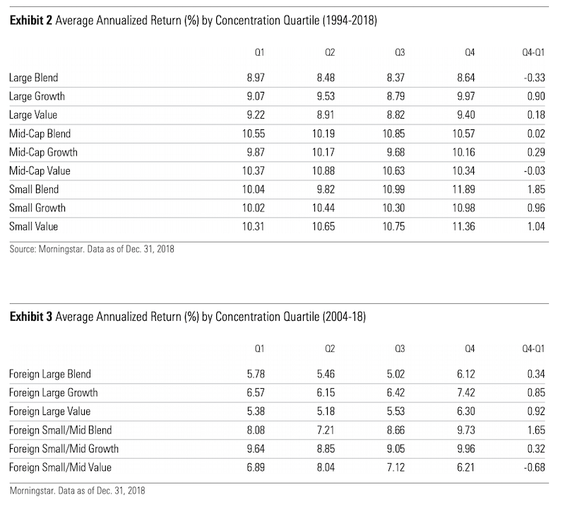

This research showed that though the most-concentrated quartile of funds (Q4) generated higher annualized gross returns than the least-concentrated quartile (Q1) in seven of the nine U.S. equity categories from January 1994 through December 2018, these differences were not statistically significant.

The same was true for foreign stock categories. Although the most-concentrated quartiles posted higher returns in five of the six categories between January 2004 and December 2018, the return differences between the most- and least-concentrated quartiles were not statistically significant. In many cases, they weren’t economically significant either.

Similarly, the most highly concentrated managers didn’t see significantly better success rates than the least concentrated. It was split roughly in half as to whether the most-concentrated or least-concentrated funds did better. But in all cases, the difference in success rates between these quartiles landed within 10 percentage points, adding further evidence that there isn’t a significant relationship between portfolio concentration and the odds of beating the market.

Risks associated with portfolio concentration

Even though portfolio managers who invest with high conviction don’t necessarily have higher odds of outperformance, our research found that the potential opportunity cost of choosing a poor manager increases. This is because concentrated portfolios have a wider range of potential returns than their counterparts who are more broadly diversified.

Return volatility is another potential risk that could increase with portfolio concentration, because of the additional exposure to firm-specific risk. However, this study found that in many of the categories, funds in the most-concentrated quartiles only exhibited slightly greater volatility than the least concentrated. And in three of the foreign stock categories, the most-concentrated funds exhibited lower volatility than the least-concentrated ones.

In those categories, the most-concentrated managers were able to partially offset their higher idiosyncratic risk by taking on less market risk than their counterparts who were better diversified. They accomplished this by favoring more-defensive investments or carrying larger cash balances.

Firm-specific risk isn’t rewarded on average, so investors may want to know that concentrated managers are taking appropriate steps to manage this risk. To assess whether their steps have been effective, investors can pay attention to portfolio volatility and market beta.

Fees tend to increase for concentrated portfolios

While there was not a significant relationship between concentration and gross returns, the most-concentrated funds tended to charge higher fees than the least-concentrated ones did. This is consistent with the idea that investors may be willing to pay up a bit for bolder active bets. However, this study suggests that it may not be worth paying a premium for a concentrated, high-conviction portfolio, since there is no evidence of significantly better odds of outperformance.