By Madison Sargis, Patrick Wang

ESG

How Does Investing in ESG Companies Affect Returns?

Key Takeaways

- Morningstar research uses a new model to compare the returns of companies with strong and weak ESG practices.

- Our study found no risk/reward trade-off to investing in ESG on a global level and only a slight cost if we limited the universe to U.S. and Canadian holdings.

- The ESG factor is distinct from other well-known style factors and deserves consideration in portfolio construction and risk management.

Read Time: 6 Minutes

Investors can build a global portfolio of companies that have positive environmental, social, and governance attributes, or ESG, without compromising returns, according to new research by Morningstar.

If investors restrict their holdings to only U.S. and Canadian securities, they would have slightly underperformed for holding better ESG securities, the study says. Meanwhile, it finds no evidence that ESG holdings reduce or increase the risk of both a global and U.S./Canadian portfolio.

To date, the quantitative study is the most in-depth look we have taken regarding the performance of ESG investments. It adds to the growing body of evidence that investors do not have to sacrifice risk or returns to invest in ESG investment vehicles.

Is There a Price to Be Paid for Investing in ESG Companies?

One of the key questions surrounding sustainable investing has long been whether investors must be willing to make a risk/return trade-off to invest in companies with strong ESG practices.

Consider this through the lens of popularity. The last few years have been explosive for ESG investing, with more ESG-focused investment vehicles available to investors and a record amount of assets flowing into ESG funds.

And as the market recognizes the value of companies’ ESG practices, it would follow that good ESG firms would be priced higher than their bad ESG peers. However, because the current price of a security and its future expected return is generally inversely related, the expected return of a company with good ESG practices may be lower than that of a company with bad ESG practices.

In other words, as investors pay higher prices for good ESG companies, there might exist a premium in return that induces investors to hold companies with poor ESG practices. This premium compensates investors for any ESG-related risks, such as environmental disasters or corporate scandals due to governance failures.

Although this makes economic sense on the surface, our study found no risk/reward trade-off to investing in ESG on a global level and only a slight cost if we limited the universe to U.S. and Canadian holdings. In addition, we found that ESG appears to be a distinct investment factor, meaning that it is either moderately or not correlated to other known factors.

How We Evaluated ESG Companies

To determine if there is a risk/reward trade-off for investing in good ESG companies, we borrowed from the premium model established by University of Chicago economists Eugene Fama and Kenneth French.

Fama and French’s model includes three factors that explain why a stock tends to return more or less than the market:

- Small Minus Big (SMB). Also known as the size factor, this measures the historic excess return of small-cap stocks minus that of large-cap stocks. It reflects that small companies outperform large companies in the long term.

- High Minus Low (HML). This factor measures the difference in returns between companies with high book/market ratios (value stocks) and low book/market ratios (growth stocks). The name reflects the pair’s observation that value stocks outperformed growth stocks in the long term.

- Market risk.

With this model in mind, we created a hypothetical portfolio called ESG Better Minus Worse, or ESG BMW. We constructed one portfolio for the global universe and one for companies based in the U.S. and Canada.

Each month, beginning in January 2009 through May 2019, we ranked every stock in these portfolios by its ESG Rating from Morningstar Sustainalytics. These ratings and rankings reflect how well a company is managing a range of ESG issues relative to its industry peer groups.

From there, we sorted the stocks into three groups and made an equal-weighted portfolio for each:

- The Better ESG portfolio included the top third of ESG companies.

- The Medium ESG portfolio included the middle third of ESG companies.

- The Worse ESG portfolio included the lowest third of ESG companies.

We then calculated the monthly return of the overall ESG BMW portfolio as the average return of the Better ESG portfolio minus that of the Worse ESG portfolio. If the market is placing a higher premium on good ESG stocks than on bad ones (meaning they’re priced higher and then returned less), thus creating an ESG risk premium, we would expect the return on the overall portfolio to be negative on average.

A Look at the Attributes of ESG Companies

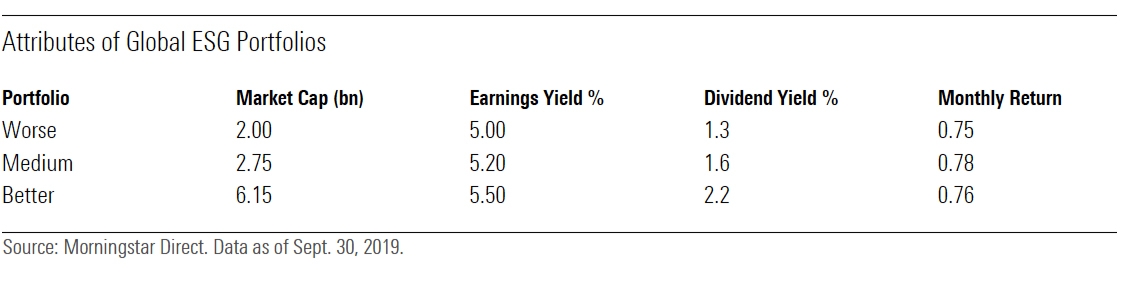

When we compared the attributes of the three global portfolios, we found that companies with Better ESG ratings tended to be larger in market capitalization and more mature with higher earnings and dividend yield. For average monthly returns, the table below shows that there were no economically significant differences between each ESG group.

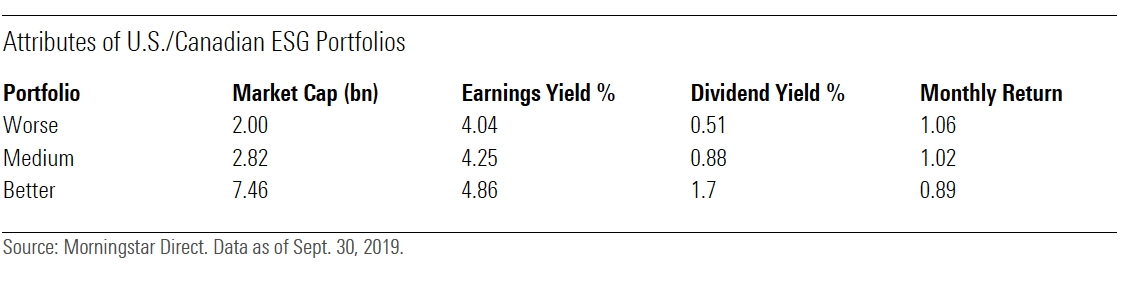

The U.S. and Canada ESG portfolios exhibited similar characteristics to the global portfolios. However, the table below shows that we also saw an inverse relationship between ESG score and monthly return: The Better ESG portfolio had a monthly return of 0.89%, compared with 1.06% from the Worse ESG portfolio. This is the first indication that investors owning high-scoring U.S. and Canadian securities may pay a penalty.

Differences in Risk and Returns for ESG Companies

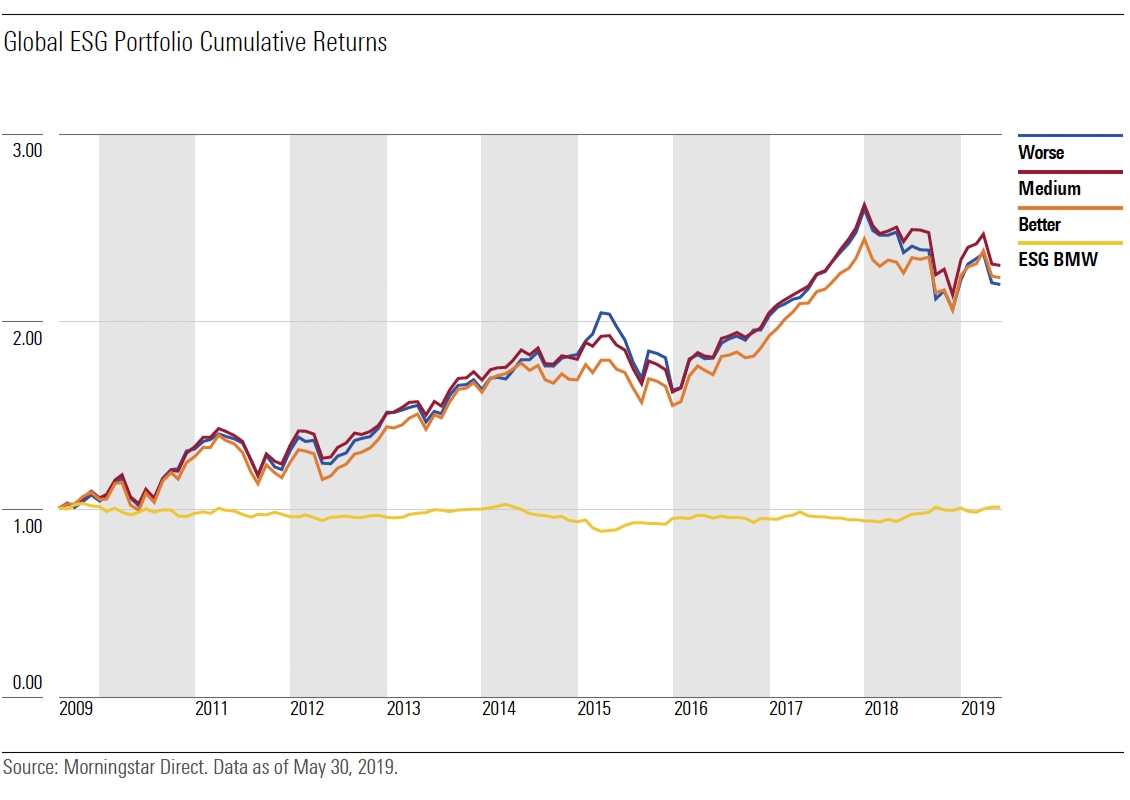

From a cumulative returns perspective, we found that the three global ESG portfolios closely tracked each other over the sample period, with no substantial differences across their returns. As shown in the chart below, this resulted in an almost flat line for the cumulative return of the global ESG BMW factor portfolio.

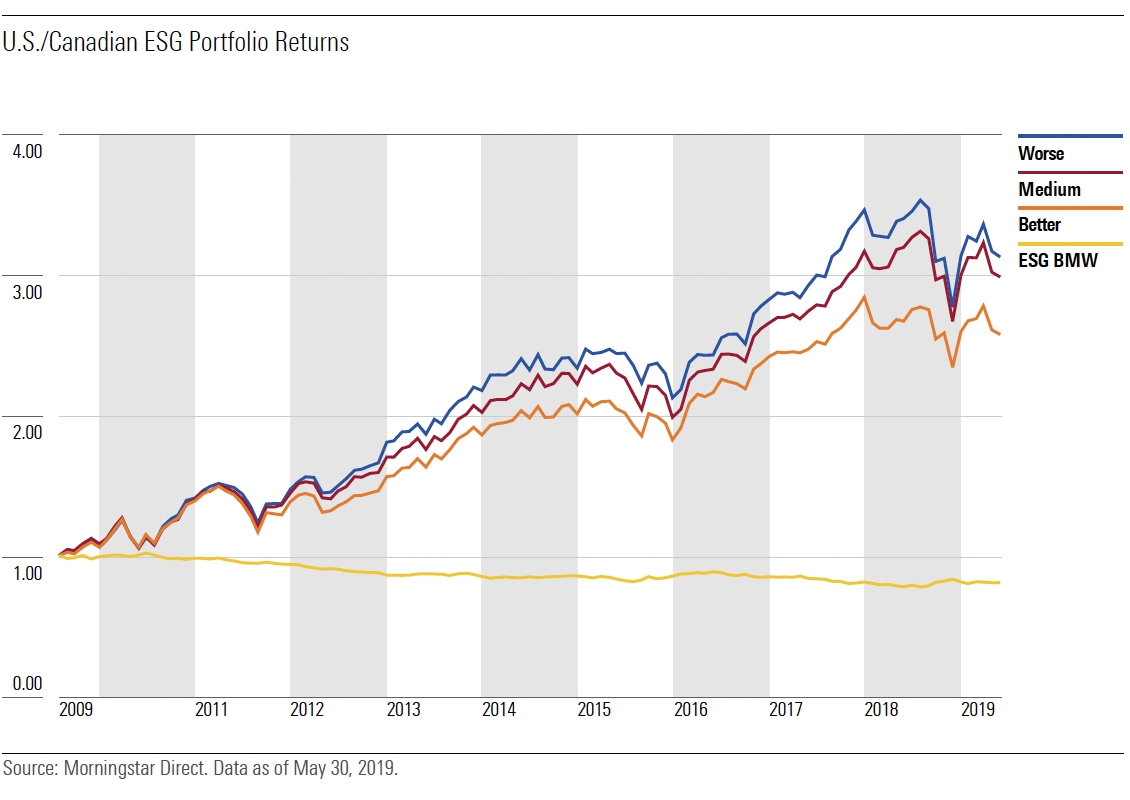

However, in the U.S. and Canada, we again saw evidence that there may be a premium for tilting toward ESG companies. The chart below shows that the Worse ESG portfolio earned 212% return over the sample period, while the Medium and Better portfolios earned only 198% and 157%, respectively. This resulted in a consistent negative return for the U.S. and Canada ESG BMW portfolios.

We think that one explanation for the return discount for the U.S./Canada ESG BMW factor is that a fair number of investors in North America are considering Sustainalytics’ ESG ratings.

Based on the portfolio returns, we then calculated risk and return statistics:

- For the global portfolios, the monthly returns, standard deviation, and Sharpe ratio were not economically significantly different. Over the entire sample period, the Worse ESG portfolio was slightly riskier than the other groups in terms of the maximum drawdown, but not by a statistically significant margin. Therefore, we can conclude that for the global universe, the ESG ratings did not sort securities into materially different risk or return groups.

- For the U.S. and Canada portfolios, we saw the opposite story. The overall ESG BMW portfolio returned negative 0.17%, yet the Better and Worse ESG portfolios exhibited similar levels of risk. In this context, ESG investors would not have benefited from meaningfully lower standard deviation or maximum drawdown. Taken together, investors are pricing in a premium for U.S. and Canadian securities scoring well on ESG measures while not reducing their portfolio’s risk profile.

Historical Returns Analysis of the ESG BMW Portfolio

We also conducted an analysis of the historical hypothetical returns of the ESG BMW factor premium to identify if it is a distinct factor or if it can be explained by known factors.

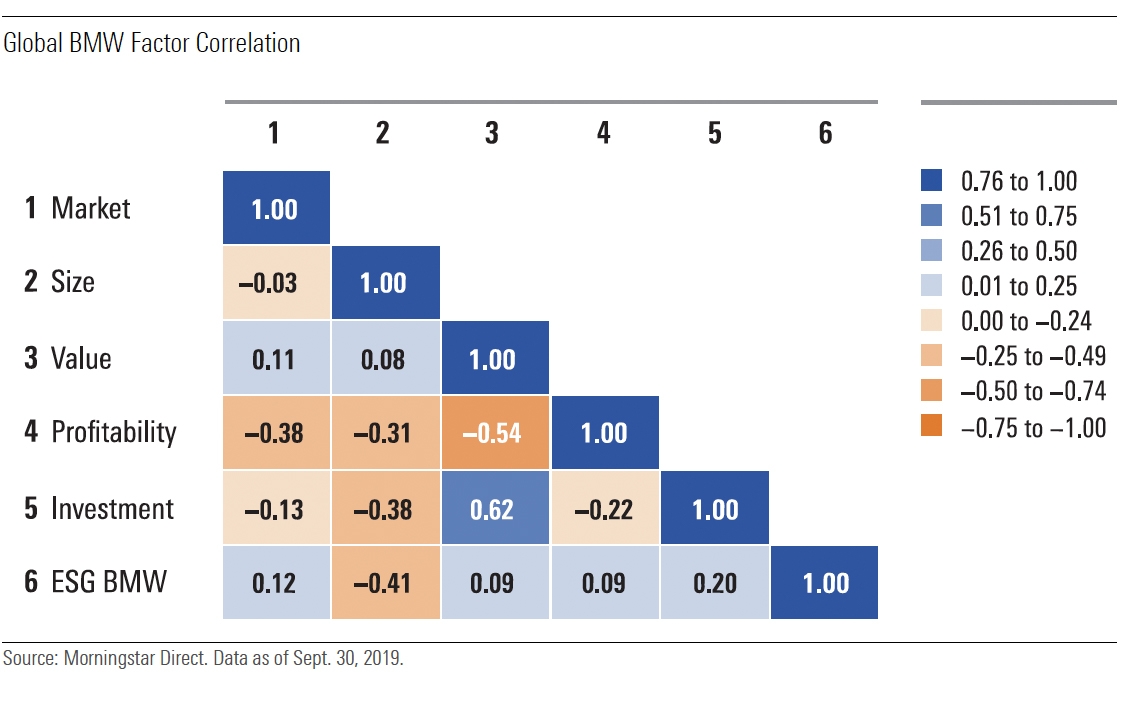

We evaluated this through Fama and French’s five-factor model, which incorporates two additional factors: Robust Minus Weak profitability, or RMW, and Conservative Minus Aggressive investment, or CMA. The chart below shows the correlation between the global ESG BMW factor and all five factors.

Not surprisingly, the ESG BMW had a large negative correlation with the size factor, aligning with our findings that companies with better ESG ratings tend to be larger stocks.

However, the ESG BMW factor was not highly correlated with the remaining factors, suggesting that the ESG BMW premium is a distinct factor. Particularly, the small correlation between profitability and investment dispels the notion that ESG could be a proxy for quality.

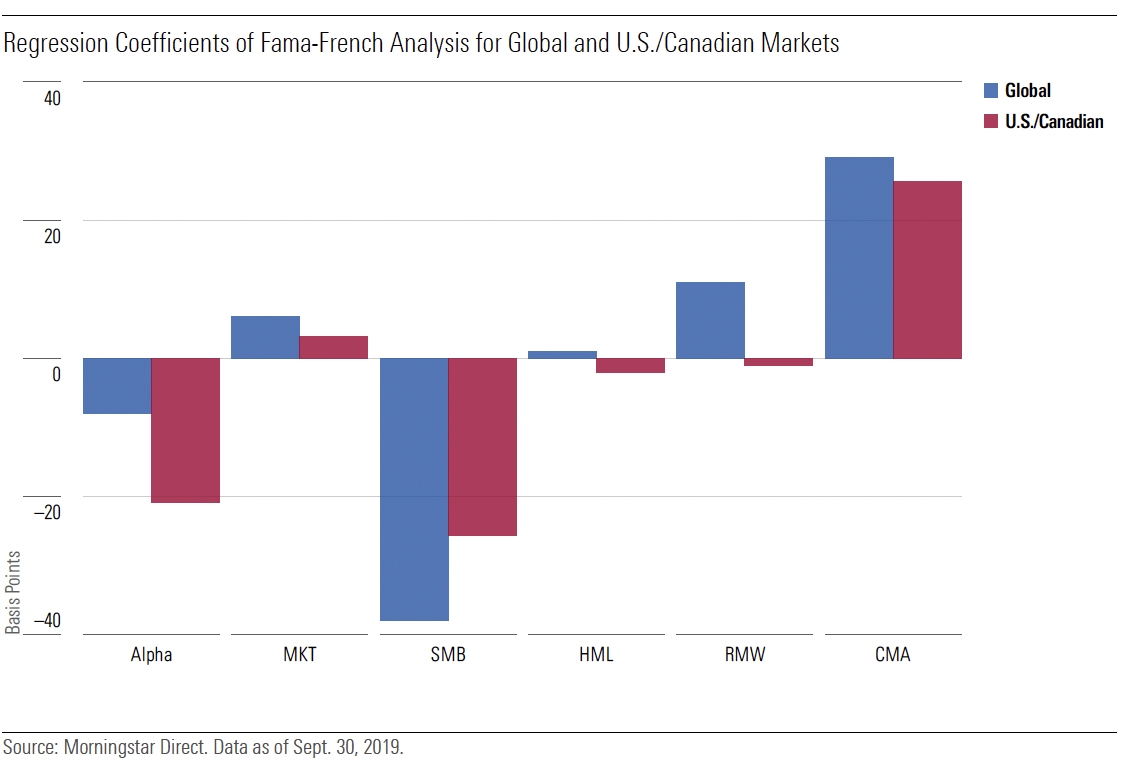

To provide further insight, we also regressed the ESG BMW factor premium on the Fama-French five factors, shown in the chart below.

Here, we found that the ESG BMW factor had a consistent negative exposure to the size factor and a positive exposure to the investment factor. This finding seems to indicate that, apart from large and more mature companies, companies with more conservative and measured investment strategies also tended to have better ESG ratings. Even though both coefficients were statistically significant, the magnitude of the investment coefficient was small, suggesting the ESG BMW factor was largely distinct.

For both regions, we saw the ESG BMW factor had a negative monthly alpha. However, only the alpha from the U.S./Canada model was statistically significant. Again, this provides evidence that investors in U.S. and Canadian companies pay a small penalty for investing in the ESG BMW factor, whereas the effect is mitigated globally.

A New Way to Evaluate Returns of ESG Companies

Across multiple tests, we’ve found that investors can build global portfolios tilted toward high-scoring ESG companies without compromising returns. However, investors building portfolios in the U.S. and Canada face a small return discount for investing in these ESG companies.

In either case, the risk associated with tilting toward a better ESG portfolio is broadly comparable to that of portfolios with poor ESG ratings.

We also found that the ESG factor is distinct from other well-known style factors, like the investment factor. Therefore, it deserves consideration in portfolio construction and risk management.

If you’re looking to start a sustainability conversation and explore ESG investments with your clients, discover Morningstar’s ESG solutions today.