Baby Bonds: Turning the Next Generation Into Investors

The program could make strides to narrow the racial wealth gap, but the details still need to be worked out.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collection focusing on the racial wealth gap. It features content from previously published research into baby bonds, linked below.

Would you believe that one single mechanism could help cut the racial wealth gap in half and turn kids into early investors with as much as $50,000 to spend once they turned 18?

The government policy that could do this: baby bonds.

Originally proposed by two academics, Darrick Hamilton and William Darity, baby bonds would see that children in the United States born to lower-income families would receive government funding, on an annual basis, that would accrue interest until they reach adulthood. They could then use those funds to help prepare for the next stage of their lives by paying for college tuition, a first home, or any other large, "wealth-building" expense they likely would have had to find other means for.

The program design most fully specified in current draft legislation is called the American Opportunity Accounts Act. Under this model, every child would receive $1,000 in an account at birth, followed by subsequent contributions of up to $2,000 each year depending on family income.

Morningstar’s policy team has researched a variety of ways that baby bonds could be effectively implemented and the potential impacts of these plans.

What Baby Bonds Could Do to Narrow the Racial Wealth Gap

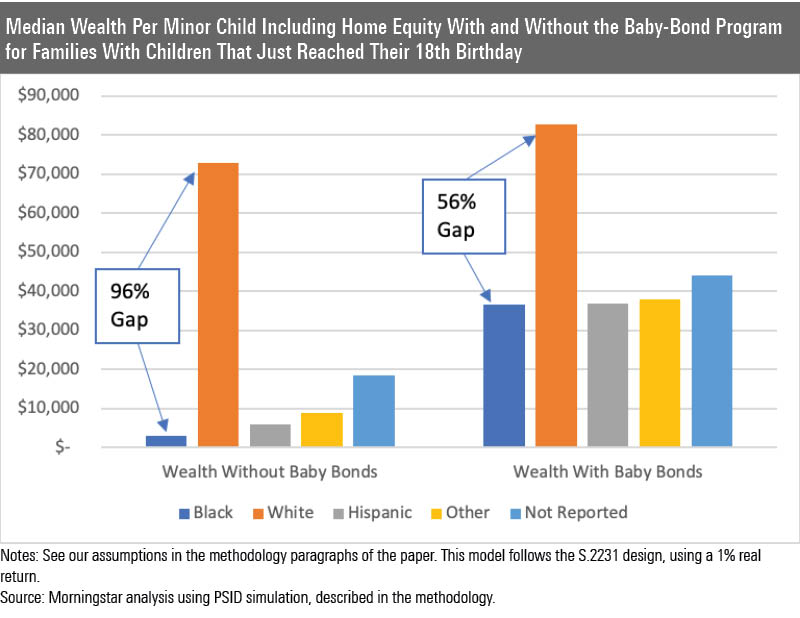

Granted that funds have time to reach full maturity, we found that baby bonds could result in children from Black and Hispanic households more than tripling their expected net worth by the time they reach the age of 18, in many cases. This impact is shown on the chart below.

Without baby bonds, we calculate the median Black family has 96% less in wealth per minor child than white families. With baby bonds, this gap would shrink by 40 percentage points: The median Black family would have only 56% less in wealth per minor child.

Similarly, without baby bonds, we calculate that the median Hispanic family would have 92% less in wealth per minor child than white families. With baby bonds, the gap would lessen so that they would have only 55% less in wealth per minor child.

We tested the program by using different return assumptions, program designs, and measures of wealth (fully reported in this paper), but we conclude that baby bonds would work to reduce the racial wealth gap. However, they will not fully close the gap due to differences in home equity between Black and white individuals in America, which would still need to be addressed through other avenues.

How Individuals Can Invest Baby Bonds Effectively

For the potential of baby bonds to be fully realized, policymakers need to balance guardrails with flexibility, while creating an off-ramp so the assets at age 18 can be invested in education, housing, or traditional investments.

We feel particularly strongly that policymakers need to explore different ways to make it easy to invest in traditional retail investments such as mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. For this reason, baby bond legislation should establish fiduciary protections for recipients to ensure they receive high-quality advice on investing their accounts after turning 18. Policymakers need to do a lot more thinking about adding protections to ensure that participants invest in low-cost, high-quality options.

As a start, we think that it should be easier to roll money into a Roth IRA, but that creates another challenge: ensuring there are sufficient protections for young adults with larger baby bond balances.

We also believe the prohibited transactions embedded in the Employee Retirement Incomes Security Act, the prudential standard under ERISA, and the SEC investment advisor fiduciary duties of care and loyalty are appropriate frameworks to use when developing these protections.

Additionally, baby bonds need to be better aligned with existing savings vehicles for children, particularly 529 plans. State treasurers run these tax-privileged college savings plans, and they will continue to market them even if baby bonds become law.

While 529 plans are of less benefit to lower-income families (who in turn have the highest baby bond account balances), our analysis reveals that the median baby bond accountholder will have $13,700 by age 18. With this money invested risk-free by design, families could potentially invest more and take more risk in a 529 plan.

Should Baby Bond Holders Take a Chance on Higher-Risk Investments?

In another paper, we examined the potential returns of baby bonds if funds were invested in riskier assets (given a reasonable investment strategy and an 18-year time horizon).

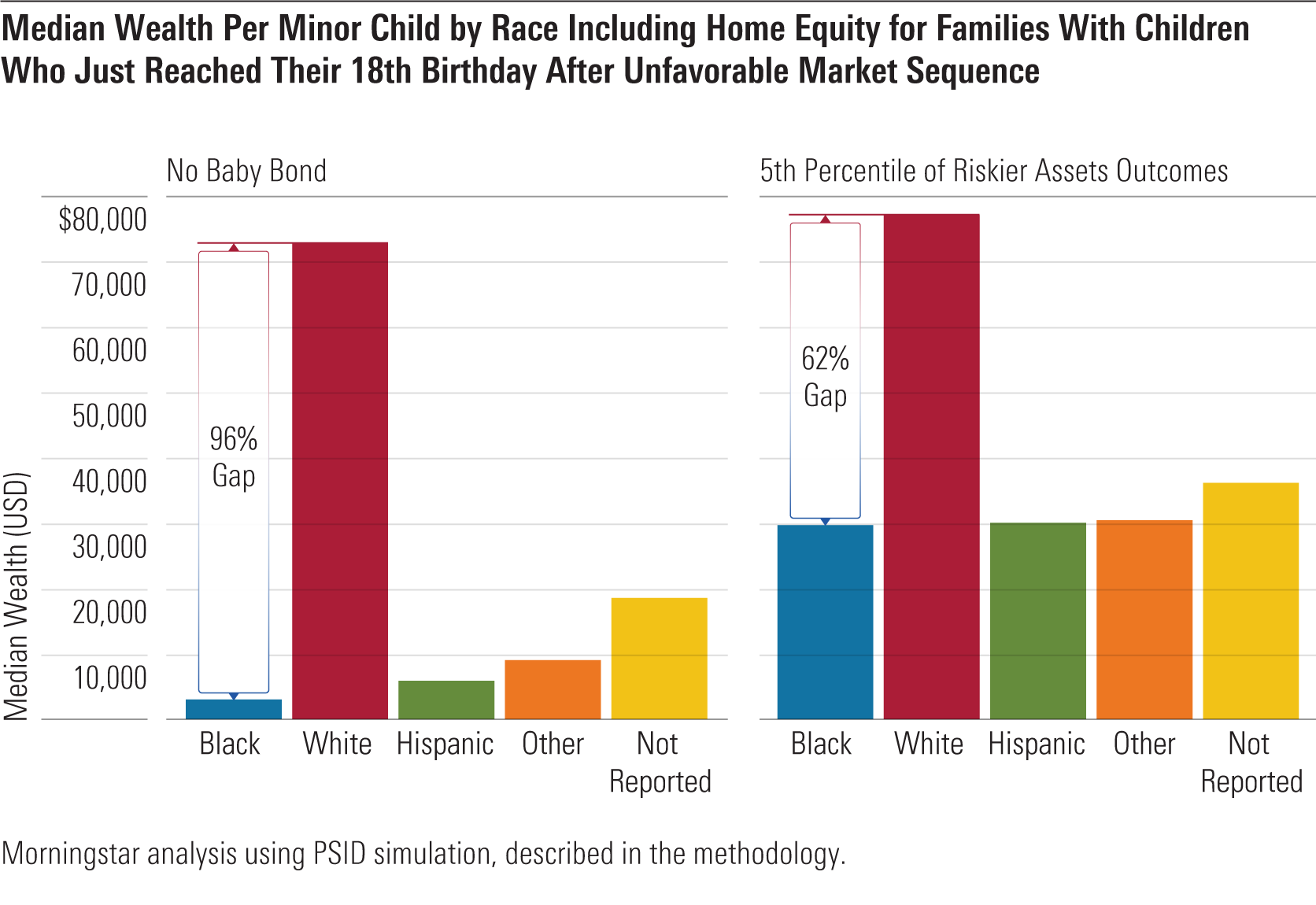

The chart below shows the difference in the racial wealth gap before simulating the effect of introducing baby bonds and after, when investment performance is at the fifth percentile of the distribution of possible outcomes. Even after an uncommonly poor sequence of returns, the racial wealth gap would still close by more than a third in terms of resources available per child at age 18.

In short, even with reasonably low returns, investing baby bonds into riskier assets would still make significant progress toward closing the racial wealth gap.

Even with the baby bonds invested in low-risk assets such as U.S. Treasuries, as proposed in the American Opportunity Accounts Act, there would be variation in balances from year to year.

However, it’s important to recognize the inconsistency that investing in riskier assets would create. Individuals who turn 18 after a rough market patch, for instance, would have substantially less in their funds than similar individuals who happen to turn 18 during a long-run bull market. Plus, this inconsistency will be the widest among the individuals receiving the largest benefits.

For this reason, policymakers will need to decide if they want a baby bond program focused on equity among accountholders or if they are willing to allow recipients to bear more risk for the potential to reduce the racial wealth gap more quickly.

How to Best Distribute Baby Bonds

In addition to determining how to best invest baby bonds, policymakers face the challenge of selecting the best way to distribute funds once accountholders come of age.

We analyzed how effective baby bonds could be as a lump sum versus monthly installments.

As a lump sum, individuals would get the most value from putting their baby bonds toward a return-bearing asset, like college education.

However, it could also be advantageous for baby bonds to be distributed as an income stream, given that a longer period is conducive to more deliberative--less impulsive--spending. It would assist individuals in handling emergencies, accumulating human capital, and even starting businesses--the same activities touted as potential benefits of a universal income.

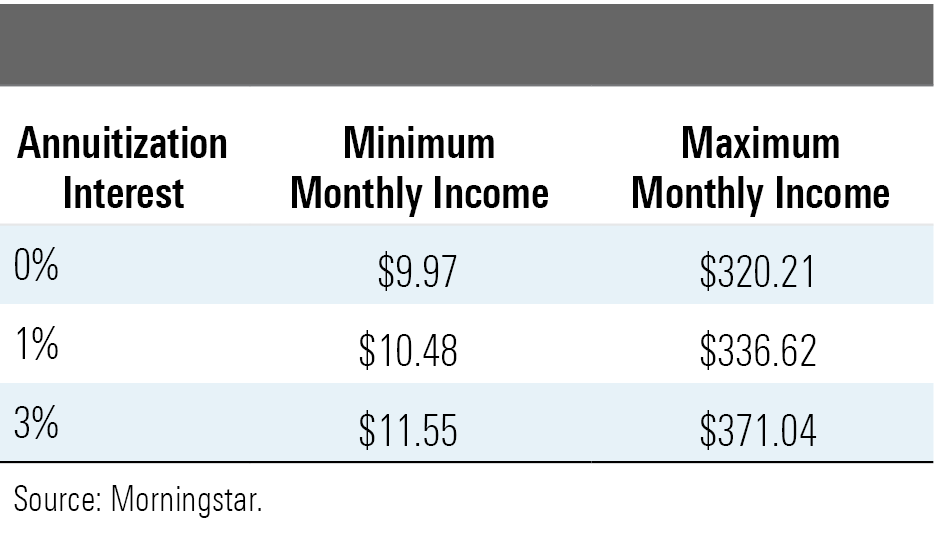

To take a closer look, we conducted an analysis of turning a baby bond into a 10-year immediate annuity. In this approach, payments are distributed over a period of 10 years, starting when the child turns 18. Depending on the income of the household, the payment could range from $11 to $370 monthly (assuming a 3% annual return). Under the 10-year immediate annuity approach, $131 would be the median monthly payment.

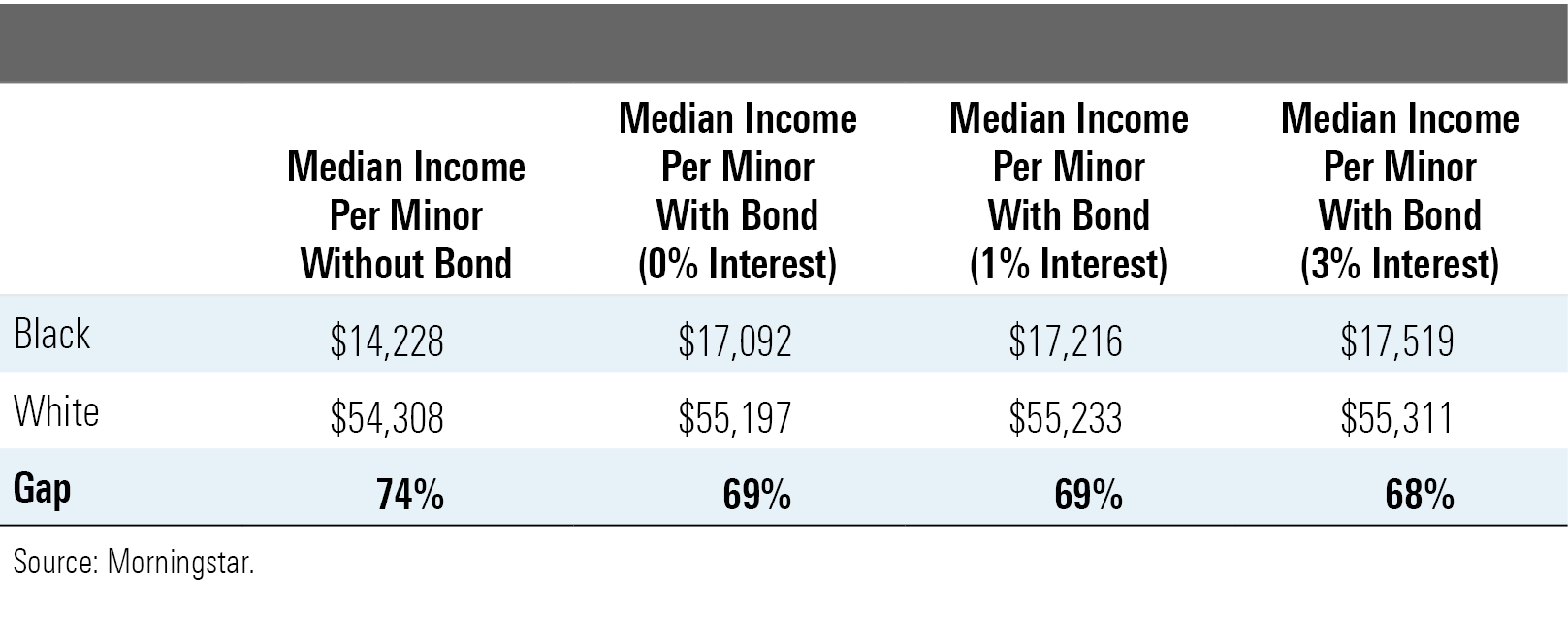

We found that the gap between Black and white median incomes per minor child reduces to 68% from 74%, assuming a 3% market return (see tables below for different simulations).

Monthly payment ranges depending on the assumed interest:

- source: Morningstar Analysts

It's important to remember that economic gap differences among races are not only influenced by money but also by differences in skills, access to networks, and time available to invest in capital.

Therefore, if these income payments can be utilized to cultivate human capital skills, expand networks, and generate time for productive activities (for example, by alleviating childcare or other responsibilities), they will be more effective in closing the income gap on a long-term basis.

While this reduction does not present a significant change to the income gap, these monthly payments could help offset the cost of emergencies--and the Federal Reserve shows half of American households don't have $400 saved for that purpose. Additionally, they could improve access to courses to improve human capital or simply help build a savings account for later use.

A Case Study in Baby Bonds

So, what would baby bonds look like in practice? For a real-world example, look no further than the United Kingdom.

In the early 2000s, the U.K. government introduced the Child Trust Fund as a means for citizens to have some sort of savings at their disposal once they reached the age of 18. The policy was ultimately abolished in 2010 under a different administration, but Child Trust Funds were in place long enough to have an impact on any U.K. citizens born between Sept. 1, 2002, and Jan. 1, 2011, according to Bloomberg Wealth.

Much like baby bonds, the Child Trust Fund offered initial grants that were dependent on a family’s income and ranged from GBP 250 to GBP 500, accordingly. Additional contributions could then come from the child’s family or gain interest in stocks over time.

Now that it’s been 18 years since this act was introduced, funds are becoming available for the first group of eligible citizens. In some cases, these citizens will be able to gain access to as much as GBP 70,000 if their accounts were managed properly.

And unlike U.S. funds such as 529s, these Child Trust Funds aren’t specifically reserved for education or any other expense. They can be spent on whatever the accountowner sees fit, and we’re curious to see what long-term impact their spending will have.

The Future Potential of Baby Bonds

In the United States, Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and Rep. Ayanna Pressley, D-Mass, have been leading the charge for baby bonds on the national stage. But more work would need to be done to see them applied in the real world.

We believe that baby bonds have enormous promise, and challenges for implementing them are no reason to give up on doing so. Still, it’s important to be clear-eyed about the messy parts of implementing such a program and ensuring it balances competing needs and meshes with existing policy.

Editor’s Note: Jasmin Sethi and Keith Reid-Cleveland were contributing writers to this article.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/f3c31470-cc00-45ac-b20f-d2928ec12660.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IJKB5DGDNJFLPP6SBNF27R3UEA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PJQ2TFVCOFACVODYK7FJ2Q3J2U.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c6d5b386-6df4-434b-bf56-ac0c9546e5aa.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/f3c31470-cc00-45ac-b20f-d2928ec12660.jpg)