Have Older Investors Become Too Aggressive?

What to make of their love affair with equities.

Bold Decisions

Last week, The Wall Street Journal’s Anne Tergesen filed a thought-provoking article titled “America’s Retirees Are Investing More Like 30-Year-Olds.” Although exaggerated, the headline is directionally correct. Today’s retirees have gotten adventurous, owning more stocks than ever before.

They are not doing so because of target-date funds. Although such funds are periodically accused (meaning, after each bear market) of investing incautiously as their target dates approach, most do not deviate greatly from the traditional approach of holding an equity position equal to 100 minus the investors’ age. Thus, the average stock weight for target-date 2025 funds is 44%—a modest 7 percentage points above what the cliché recommends.

However, reports Vanguard, when its 401(k) participants make their own choices rather than delegate the responsibility to professionals, they are much more aggressive. According to the 100 minus age formula, participants who are at least 55 years old should invest a maximum of 45% of their assets in stocks. In practice, though, two thirds of Vanguard’s older do-it-yourself 401(k) investors have most of their assets in stocks.

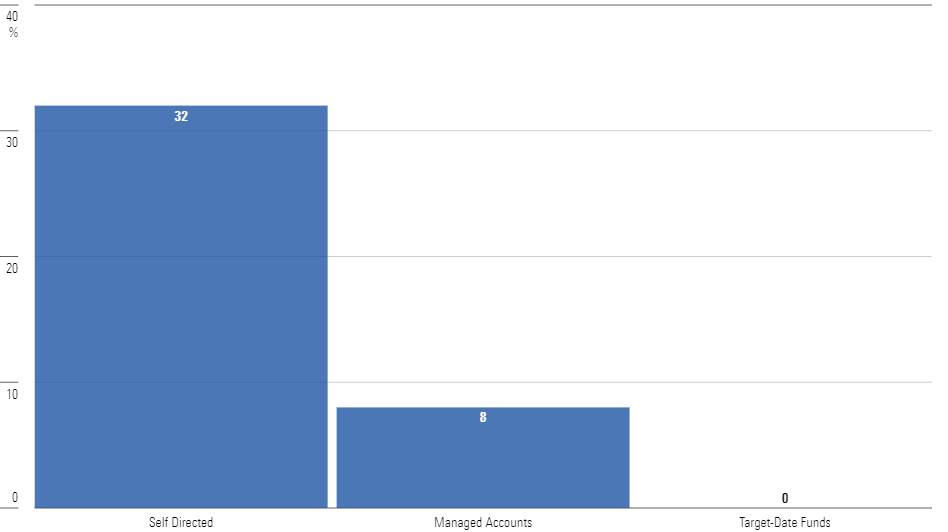

Here is another way of looking at the numbers. By any reckoning, a 70% equity position is aggressive for investors over the age of 55. Few institutional investment managers would make such a decision. No Vanguard 401(k) participant holding an appropriate target-date fund has such a steep stock allocation, and only 8% of those who are enrolled in managed accounts. But 32% of the company’s self-directed 401(k) investors who meet that description have done so.

Vanguard's Older 401(k) Participants

More Evidence

The pattern extends past both 401(k) accounts and early retirees. Among Vanguard’s taxable accounts, states Tergesen, 20% of the company’s customers who are aged at least 85 years have essentially everything in stocks. Fidelity’s clients, she reports, are similarly audacious.

These figures merit several caveats. Two thirds of Vanguard’s 401(k) participants own either target-date funds or a managed account and thus are more cautiously positioned. With the remaining customers, as well as with Fidelity’s data, we do not know about their additional assets. Perhaps they hold large amounts of cash and bonds in other accounts. Nor do we know whether Vanguard’s and Fidelity’s customers accurately represent the overall investor universe—although they probably do, given the size of those organizations.

However, as these conditions were all present at the start of the past decade, and the number of older investors with elevated equity allocations has risen by 25% since that time, the trend undeniably exists.

Why?

Tergesen suggests three reasons for the change in investor attitudes.

1) Personal Experience

Three years after Businessweek published its infamous “Death of Equities” cover, the Great Bull Market started, in 1982. With only brief interruption, it has not ceased. Consequently, few U.S. equity investors have faced a long-term decline. Commented Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller, “The spirit of the times is ‘Don’t worry about the markets crashing. They will come back up and set new highs.’”

2) Weak Competition

When the New Millennium dawned, on Jan. 1, 2000, 30-year Treasury bonds paid 6.63%. Had that yield persisted, permitting bondholders to reinvest their coupons at that same rate, patient investors would have converted a $10,000 initial purchase into more than $45,000 today.

Of course, that did not happen. Bond yields continued their long-term decline, and cash payouts fared worse. Stocks became the only legitimate game in town—and investors very much noticed.

3) Excess Assets

Consumer gloom notwithstanding, Americans on average are wealthier than they have ever been, especially within the investor class. Of course, those with substantial portfolios remain the exception rather than the rule, but the exceptions are growing. In 2020, for example, 9% of Americans between the ages of 70 and 74 were worth more than $2 million, not counting their home values.

Assuming moderate lifestyles, such retirees can amply afford stock market risk. For example, Tergesen spoke with a 72-year-old who owns a $3 million portfolio and who lives primarily on Social Security. He is 98% invested in equities.

Further Explanations

Those claims are surely correct. But I would cite two more factors.

1) Incomplete Rebalancing

Many investors, including yours truly, rebalance their portfolios irregularly. (”Irregularly” being my euphemism for “almost never.”) Some of the increase in equity allocation has therefore been caused by inertia. That holds particularly true for 401(k) accounts, which are predominantly owned by zombies. In 2002, reports Vanguard, only 6% of its do-it-yourself 401(k) participants made even a single trade. (The percentage was lower yet for target-date shareholders.)

2) Failing Hedges

Presumably, older investors would temper their stock market enthusiasm if acceptable alternatives existed. There are other ways to diversify portfolios besides bonds and cash. However, gold bullion has appreciated by a modest 25% over the past decade, oil prices are down, and as related in last week’s column, funds that purport to hedge stock market downturns have languished.

Where else is there to go but stocks?

Conclusion

My contrarian side regrets the stock market’s popularity. Better to invest in securities that are distrusted than those that are loved. (Even growth-stock investors share that belief, although they usually cannot find unloved companies that meet their standards.)

But I console myself with two considerations. For one, retail shareholders are but a single segment of the stock market. Not all investor groups have behaved similarly. For example, Fortune 1000 pension plans have slashed their exposure to U.S. stocks in recent years. For those worried that equities might be overbought, that is an encouraging offset.

The other counterargument is that, at least on the surface, U.S. equities do not appear to be egregiously priced. The following chart shows the price/earnings ratio for the Morningstar US Market Index since January 2000. The current figure is moderately above the 23-year norm, but not so high as to set off alarm bells.

Price/Earnings Ratios

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZI3W4F3IORA73KFWC7VAFNOJJ4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CWMPLAZER5HFBGFDFB45VCOUHI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VCYGUEZEV5DA3PVEIJNCMYA7AU.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)