Are We Losing Ground?

Common measures of living standards miss the cyber economy.

From politicos on Capitol Hill to the halls of academia, the specter of stagnating living standards is almost taken for granted. But are most Americans really no better off, or even worse off, than they were a generation ago?

The view of stagnating living standards stems from a set of macroeconomic indexes that imperfectly serve as a proxy for how well people are doing. A gap between individual experiences and the numbers has always existed, but as our economy has evolved from an industrial base to a service base and, ultimately, to an information base, the perception of the gap has widened. Moreover, as we transition from an easy-to measure “terrestrial” economy to an incorporeal “cyber” economy—with its abundance of cheap, free, and time-saving services—the disconnect between the numbers and our living standards will grow.

Until better ways to measure today’s economy come into general use, understanding this gap can help inform investors’ sense of well-being today and their assessment of their future.

Paint by Numbers The economy exists through a web of numbers. The benchmark macroeconomic indexes, such as the Consumer Price Index, gross domestic product, and the unemployment rate, serve as primary vehicles by which we formulate our statistical picture of the economy and, by extension, a view of our standard of living. The 2016 election focused on economic dislocation, both perceived and real. Many observers attributed the unlikely run of Bernie Sanders and the even more unlikely success of Donald Trump to economic anxiety. And there's little doubt that politicians and the media played up economic anxiety to garner votes and page views.

Indeed, there is evidence that standards of living have stagnated. Since 1979, annualized real wage growth as measured by full-time median usual weekly wages has increased for U.S. workers by a paltry 0.15%.[1] If we break it out between men and women, the numbers look worse. Real wages for men declined at an annualized rate of 0.12%. They grew for women at 0.6%, but this was a function of more women moving into high-paying professions, ones in which real compensation has for the most part stagnated. Other factors such as labor’s falling share of national income—which has accelerated since the beginning of the century—imply stagnating if not falling welfare for a majority of Americans.

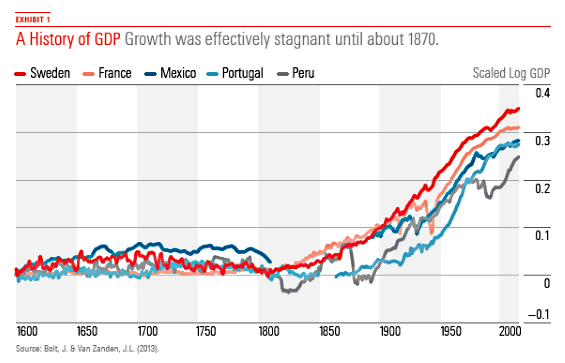

Proxying Living Standards The two most widely used measures to represent living standards are real GDP per capita and total factor productivity.[2] The latter, while theoretically preferable, is difficult to calculate and not derived using an agreed-upon methodology. The former, however, is simply inflation-adjusted GDP divided by the number of people in the economy. The intuition that binds real GDP per capita to living standards is that if the price of goods and services increase in real terms, the quality of those goods and services must have increased. This is definitional. If you pay more for the same service or commodity, that is, by definition, inflation. It's human nature to weight the recent past more than the distant past, so it's not surprising that we tend to extrapolate growth rates of the recent past into the future. This is wrong. An important artifact of the indexes is that they cover a period of extraordinary economic and technological development. Reliable macro data before the 20th century is hard to come by,[3] but we do have real-GDP-per-capita estimates via the Maddison Project.[4] For the bulk of human history, increases in living standards were stagnant (Exhibit 1). We have a pretty good idea that living standards in 1600 in Portugal were not much different from those in 18th century Italy.

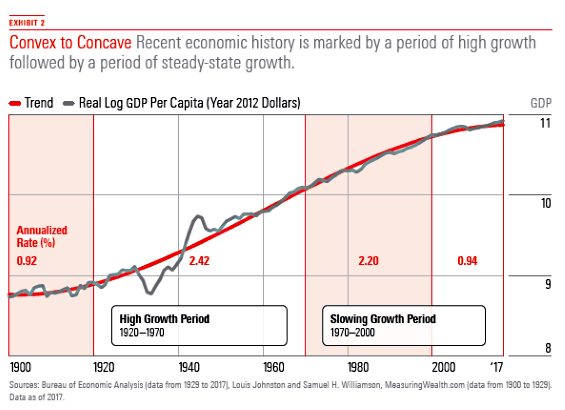

Around 1870, this started to change. With groundbreaking innovations such as the internal combustion engine, the beginnings of the assembly line, and the proliferation of the corporate model, we see the birth of the modern economy and the generation-to-generation increase in living standards that we’ve come to view as a natural feature of a healthy economy. Exhibit 2 plots the growth of real GDP per capita. Note that the trend line from 1920 to 1970 is convex, increasing at an accelerating rate, whereas from 1970 forward, we see a continuation of high growth but at a decreasing rate. The line becomes concave. After around 2000, the line flattens even more; the growth rate for this period is less than half of what it had been in the previous period.

All this may seem somewhat abstract, but if we were to step into a time machine and jump back 40 years to 1978, we’d find ourselves in a strikingly similar physical environment to today. With the exception of the Internet and smartphones, negotiating your day-to-day activities would be straightforward. But take someone in 1978 and move them back 40 years to 1938, and things would be quite different. Trivial tasks like using the telephone and even driving would require some tutoring. Modern conveniences such as air conditioning, dishwashers, and laundry machines were uncommon. Move a person in 1938 back 40 years to 1898, and the environment would be almost completely unfamiliar: no electricity, no mass communication, schooling ending at age 14, and average life expectancy of around 52 years. The past is a different country that gets increasingly alien as we travel back through it. Conversely, the future is another country that gets increasingly familiar. Things change less radically. Standards of living are growing at a decreasing rate as we move through the 21st century. But why should this be so?

Explaining the Slowdown Several theories explain this slowdown. All of them rest on the premise that the mid-20th century period of explosive growth was an anomaly. Among the reasons given for the post-1980 slowdown are the exhaustion of undeveloped and underdeveloped land and the tapering of the entry of women into the workforce.

Importantly, most of the explosive innovation of the 20th century was physical and more easily measurable—seemingly captured by the indexes. That said, index creators—such as Simon Kuznets, the father of national accounting— warned that this data could not be used as a proxy to gauge the welfare of people because too much information is left out. The economic value of child-rearing, for example, directly affects the quality of human capital, which is itself the key ingredient in productivity growth.[5]

Perhaps the more difficult problem is accounting for the changes to “quality” in a good or service. Improvements to products are typically incremental, and what constitutes a quality improvement may be subjective. But it’s essential to understanding growth. If inflation is overestimated, real GDP growth will be underestimated. The tech revolution made this a huge issue—not just with respect to technological improvements to the quality of finished goods, but also to technology’s impact on the production process and, ultimately, an economy’s time endowment. This difficult-to-account- for impact of technology amounts to “technological leakage” from the indexes.

When Less Is More This issue was addressed by the Boskin Commission report—a 1995 government-sponsored study that examined biases in the CPI. Boskin held that the CPI overestimated inflation and that the biggest culprit was a failure to adjust for quality improvements. In other words, if one or more components of a good have been improved but the price has not changed, the good has effectively decreased in price. This implies that stagnating or even declining real wages may be less troublesome with respect to consumer utility. If you're getting more for less, you may be holding ground without realizing it.

This issue of unpriced (or underpriced) quality improvement is critical. Take, for example, the price of recorded music. In 1920, the price of a phonograph record (one or two tracks) was a little over $12 in today’s dollars. By the mid-1970s, the cost dropped to about $4.44 in today’s dollars, and quality had greatly improved to the point that the dynamic range was equivalent to that of the human hearing range. Portability and longevity also had massively improved. By 2007, one could buy a song on iTunes for $1.21 in today’s dollars. Today,

The Element of Time

The rise of the cyber economy has exacerbated the problem of what’s missing from economic data. This is largely because of the time dimension. The time needed for the bulk of information gathering has compressed dramatically into a Google search and a few clicks. Knowledge acquisition in general is virtually free. The time investment has collapsed. And these activities are inherently accretive to human capital and to technology-driven advances—not to mention leisure activities like time spent on

Applying a value to the time saved through shopping, retrieving information, and socializing over the Internet is difficult to estimate but extraordinarily important. Attempts to measure it include the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Survey, which solicits households for their time spent on various activities from sleeping, shopping, and preparing meals to using the Internet and computers. Empirical research of time usage is new, although the concept of time as a measurable asset is not.[6] Fortunately, the empirical work more or less intersected with the tech revolution, so we are now beginning to build a time series of data that can help us make better estimates of consumer welfare. Researchers are using this data to better account for Internet-based consumer welfare and consumer surplus—the idea being that if we know the amount of time someone is spending on the Internet, we can price it. One recent effort estimates that the welfare gained from “free” products added 75 basis points to annual GDP from 2007 to 2011.[7] Getting at least some of this information into the official indexes is now technically feasible.[8]

Impact on the Future So, are we losing ground, or are we just unable to see the ground on which we stand clearly? With respect to technological innovation and the improvement in living standards, the answer to both questions appears to be no. We may not be able to measure growth in living standards through productivity numbers, but it's hard to argue that living standards are not better today than they were even 15 years ago. The time endowment given to us by smartphones, online shopping, and online learning has been revolutionary, and this revolution is still evolving.

People invest today to derive utility from consumption tomorrow. Consumption has traditionally been expressed in the indexes as a money-based transaction. As we move deeper into the cyber economy, money-based transactions will increasingly fall short of capturing significant economic activity and, thus, understate real growth rates, making it hard to tie growth rates to living standards. Quality improvements and the proliferation of free goods and services mean that the actual costs of an investor’s consumption basket will increasingly decline.

[1] Full time usual weekly real earnings for ages 16 and above. Bureau of Labor Statistics (January 1979 through July 2018). [2] Sometimes referred to as "multifactor productivity." [3] A good deal of pre-20th century data was assembled only recently. For an early and well-known example, see Homer, S. & Sylla, R., originally published in 1963; latest edition, 2005. A History of Interest Rates (Wiley Finance, 4th Edition). [4] Bolt, J. & Van Zanden, J.L. 2013. "The First Update of the Maddison Project: Re-Estimating Growth Before 1820." Maddison Project Working Paper WP-4, January. [5] UNICEF. 2014. "Early Childhood Development: The Key to a Full and Productive Life." White Paper, March 15. [6] Becker, G.S. 1965. "A Theory of the Allocation of Time." The Economic Journal, Vol. 75, No. 299, PP. 493–517. [7] Brynjolfsson, E. & Oh, J.H. 2012. "The Attention Economy: Measuring the Value of Free Digital Services on the Internet." ICIS. [8] Bean, C. 2016. "Independent Review of UK Economic Statistics." March.

This article originally appeared in the December/January 2019 issue of Morningstar magazine. To learn more about Morningstar magazine, please visit our corporate website.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-29-2024/t_eae1cd6b656f43d5bf31399c8d7310a7_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GJMQNPFPOFHUHHT3UABTAMBTZM.png)