Is the Conventional Wisdom About Lineup Size Still Correct?

A new Morningstar paper questions the status quo.

A fascinating new paper by Morningstar's head of retirement research, David Blanchett, along with Professor Michael Finke, upends conventional wisdom on how retirement plan menus should be structured, but it also offers some useful insights about the behavior and performance of individual investors in those retirement plans that we can all take some lessons from.

As I noted in my very first column looking at how many funds one really needs in a portfolio, experts have generally advised against creating retirement-plan lineups and individual portfolios overloaded with too many funds. A number of reasons underlie that advice, but one of the chief rationales (particularly for retirement plans) is that too many options leads to "choice overload." That's the situation in which participants, overwhelmed with the number of options before them, decide to take the route of doling out their allocations equally across all the plan options--or worse, to not participate in the plan at all.

Because this new research from Blanchett and Finke has potential implications for how retirement plan sponsors and consultants think about plan-lineup construction (Morningstar's manager selection team, of which I am a part, provides such consulting through its Fiduciary Services program), I am going to use this column to review the major findings of Blanchett and Finke's paper, raise some questions and thoughts for future research, and consider the potential implications. In addition, I'll look at a few relevant takeaways for individual investors.

Reframing the Question One of the insights that spurs the authors' thinking is that a significant shift has occurred in the retirement market since much of the early research about investor decision-making was conducted. In particular, the availability and usage of professionally managed allocation vehicles (such as target-date funds) have increased substantially since the Pension Protection Act of 2006 allowed employers to automatically enroll workers into such investments (known as "default" investments when used in this way).

Blanchett and Finke thus asked the question, Does plan size (the number of investment options) have any effect on how willing participants are to use the default investment option, given that other studies have shown (and intuition suggests) most investors will get a better outcome choosing the default than managing their own portfolios? Blanchett and Finke make the assumption that plan sponsors would ideally like to see more of their workers accept the default option. This seems reasonable, but it also raises the bar on the plan to make sure that the default investment option is of the highest quality.

To test their question, the authors reviewed data from a single recordkeeper that incorporated around 645,000 participant account allocations across 545 401(k) plans. This is a substantial data set, and they found that the demographic characteristics of the participant base were similar to those of populations found in other studies.

A Surprising Finding I won't get into the weeds of how Blanchett and Finke conducted their analysis (those who wish to can consult the paper directly), but suffice it to say that their work consisted of 1) careful analysis of what percentage of participants selected the default investment option when given the choice (what the authors call "default acceptance"), sliced and diced by different factors and demographic attributes; and 2) sophisticated quantitative regressions run as another way to measure the impact of plan size on default acceptance relative to other variables.

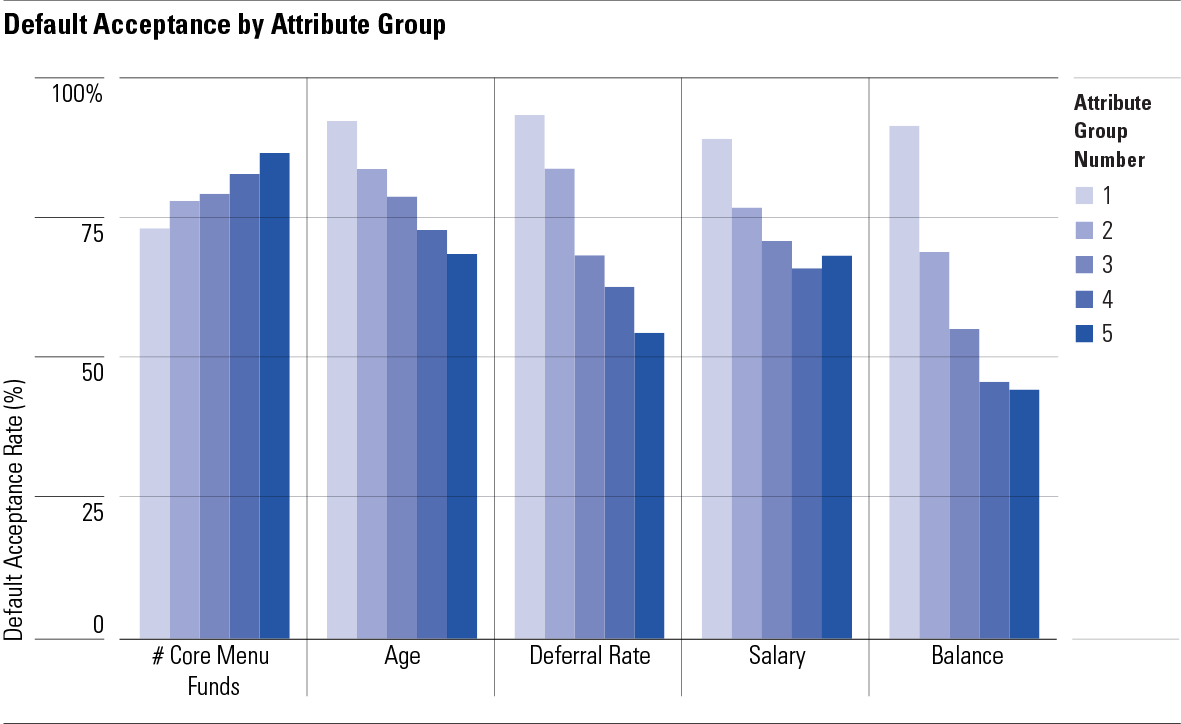

The results of both forms of analysis showed quite clearly that default acceptance rates were higher in plans with more funds. In other words, the more choices on offer in the plan, the more likely participants were to opt for the default. A key finding is that the percentage of investors who opted for the default investment option rose from around 74% in plans with the smallest menus (around 10 funds) to 87% for plans with the largest menus (around 30 funds). Exhibit 1 shows how various factors affect default acceptance among subcohorts in each area.

Whereas historically, choice overload was seen as a negative in that it caused "analysis paralysis"--and thus a failure to put money to work in the markets--this study takes the view that choice overload turns into a positive in the post-Pension Protection Act world, because failure to take action generally equates with ending up in a preferable default investment.

A Path to Excess Alpha? In the second part of their study, the authors took on the less headline-grabbing but still important question of what effect plan size might have on participants who chose to reject the default option and manage their own portfolios--a profile typically associated with more-sophisticated investors.

This section of the paper makes two key findings. One is that prepackaged multi-asset vehicles outperformed self-directed portfolios by significant margins (on the order of 54 basis points annually). In short, even self-directed investors who think they know what they're doing on average can't do better than professionally managed allocation funds--and they lag by nontrivial amounts. This should give pause to even more-sophisticated investors when they consider managing their own 401(k)s.

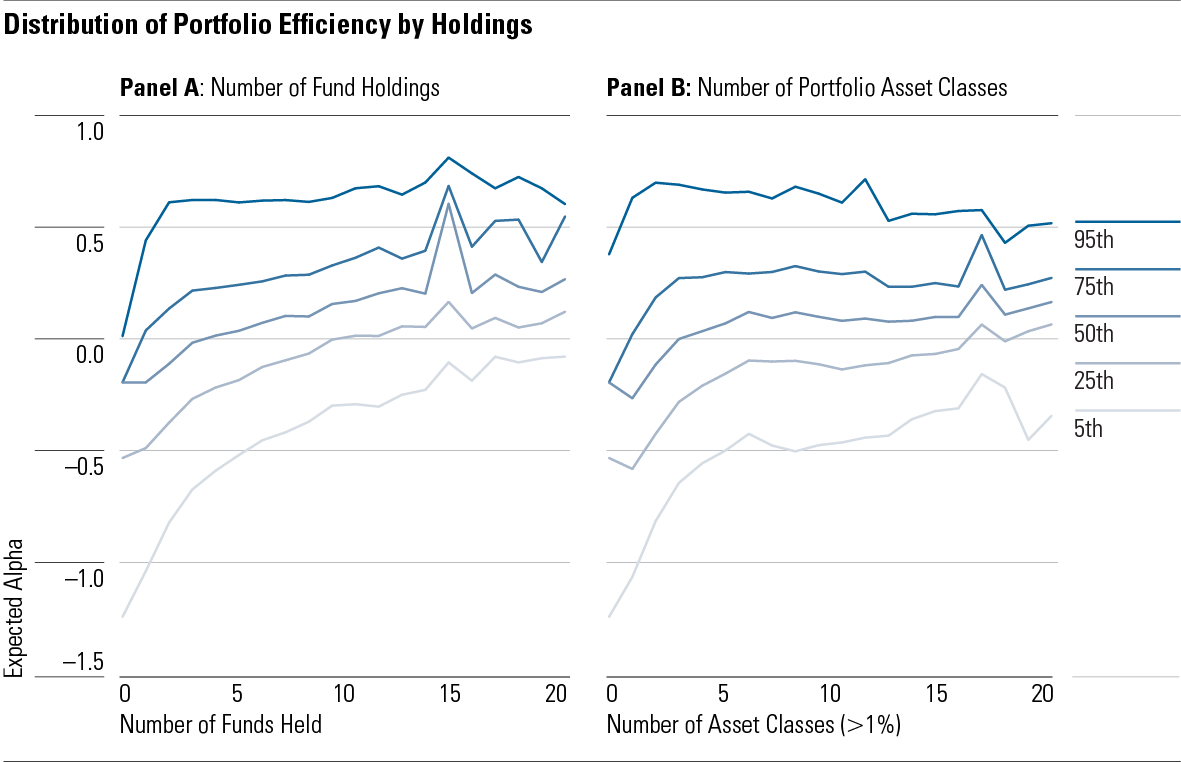

The second finding, perhaps less intuitive, is that self-directed investors have improved alphas when there are more funds in a plan menu. Blanchett and Finke show that this largely derives from improved diversification, as investors tend to choose more funds and asset classes when there are more options in the lineup.

It should be noted, however, that the improvement effect is small. The authors estimate that a plan whose menu increased to 30 funds from 10 could expect to see a rise in expected alpha of 10.8 basis points (based on an assumption of adding three funds to their portfolios). To put that in perspective, for the median plan balance of $44,000 in the authors' data set, the expected alpha increase would result in an additional $80 in performance per year.

Finally, it's worth noting that the efficiency improvement effects tend to level off as the number of funds or asset classes in a participant portfolio increases (see Exhibit 2). The marginal effect of improvement is much greater going to 10 funds from five than to 20 funds from 15, for example. Thus, the improvement results would likely be most noticeable in plans that currently have relatively constrained menus, not those that are already widely diversified.

Still, 10.8 basis points is not nothing, and, more importantly, no negative effect was associated with increasing plan menu size (aside from the additional due-diligence burden associated with a larger menu), so plan fiduciaries could feel comfortable knowing that while expanding the menu might cause more people to select the default option, it would at the very least not hurt the remaining self-directed investors, and might even help.

Quibbles, Questions, and Final Thoughts This is a promising theory with some intuition (and a solid dose of data) behind it, but it's still just that--a theory. I would suggest that one next step for an enterprising researcher to assay would be to conduct qualitative, behavioral research into a group of investors with similar demographics to those covered in the study. That would allow for a more nuanced understanding of the competing motivations at play when a participant decides on whether to accept a default enrollment, and a more solid foundation for any decisions a plan sponsor might make to increase the number of available options in a plan.

As noted above (and as Blanchett and Finke acknowledge), more research of this type across other recordkeeping platforms would help validate the results, and additional research into interaction effects and other topics would provide additional useful context. Furthermore, plan sponsors should ask whether other means (such as improved participant education efforts) can successfully promote increased default usage without restructuring their lineups. Still, the research does suggest that plan sponsors that wanted to expand from core lineups could potentially increase default usage without detracting from the performance of self-directed participants. In those cases where sponsors wish to nudge more workers toward a default investment option, plan fiduciaries should take extra pains to select an investment type and manager with sterling qualities.

The research also offers some secondary lessons for individual investors. For example, the research shows that most self-directed investors in a retirement plan would be better off in a professionally managed portfolio like a target-date fund. Most of us have a cognitive bias toward believing that we can do better than everyone else out there, even when statistics indicate otherwise; it probably behooves self-directed investors to take an honest look at whether their own results have been superior to what they might have earned in an allocation-type investment vehicle. Readers of Morningstar.com, of course, are more investment-savvy than even the typical self-directed retirement plan investor and likely can do better managing their own portfolios than the average investor. Still, for the sake of convenience there's nothing wrong with using a target-date fund, if there's a strong one available in your 401(k), and focusing your portfolio-management efforts elsewhere.

In a different vein, the research reinforces the wisdom, through empirical data, that diversification in the form of additional asset classes improves risk-adjusted returns (though it does not tell us which asset classes provide more benefit, or how much to allocate). It's another reminder, as we approach year-end, to make sure our portfolios contain an appropriate level of diversification to help reach our long-term goals.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/05-01-2024/t_17b16ff580be466186dfca2760195b1f_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BZ4OD6RTORCJHCWPWXAQWZ7RQE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/2e13370a-bbfe-4142-bc61-d08beec5fd8c.jpg)