'Animal Spirits' and Business Cycles

Emotions and behavior can affect economic output as much as, if not more than, core economic factors.

This is the second in a series called Behavioral Finance and Macroeconomics. We will explore the effect behavior has on markets and the economy as a whole--and how advisors who understand this relationship can work more effectively with their clients. (Access more articles here.)

It is important for advisors to understand the impact human behavior has on the economy and how economists think about the subject. This can help you explain to your clients what happens to mass psychology during recessions and expansions--and when recessions (or worse) happen, what psychological factors bring the economy and the markets back on track.

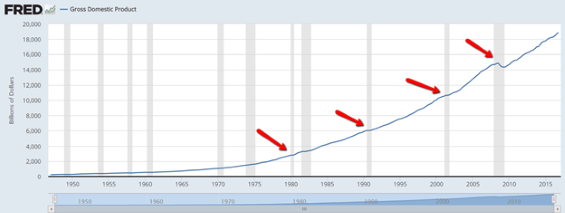

The following chart shows GDP growth in the United States from the 1940s to today. There have been 11 recessions during the period, as represented by the gray columns.

What causes recessions? What brings the economy out of a recession? And what impact do consumer and investor behavior have on the business cycle?

To answer these questions, it's important to understand a concept developed by John Meynard Keynes called "Animal Spirits."

In "The General Theory of Employment, Money, and Interest," Keynes describes economic behavior not just by core economic principles, but by emotional and behavioral factors as well:

"Our decision to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits — which is a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities."

Keynes showed that in addition to core economic variables such as interest rates, wages, etc., psychology plays a role in the ups and downs of the economy. The collective personality of a society can reinforce both positive and negative economic cycles.

For example, Keynes explains why the depression of the 1930’s lasted so long--i.e., masses of depressed people--and why we broke out of the depression after the start of World War II when people felt united in spirit.

"Animal spirits" help to explain economic cycles because emotions and behavior affect economic output as much as, if not more than, core economic factors. Moreover, advisors need to understand the extent to which emotions and behavior influence market behavior and bubbles that get created, such as the internet stock-market bubble that burst in 2000 and the real estate bubble of 2008. In those periods, fear and greed drove consumer and investor decision-making and created bubbles that burst.

What measures can we use to gauge sentiment?

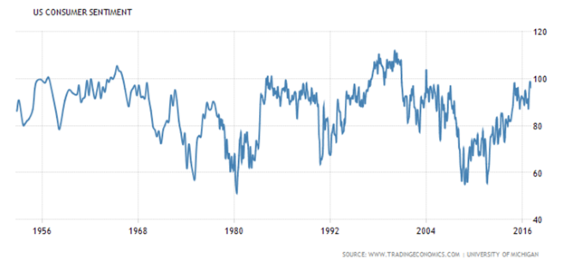

Perhaps the most widely used measure of "animal spirits" was developed by a psychologist at the University of Michigan in the 1950s named George Katona. He developed the consumer confidence index that is widely used as an indicator for understanding and predicting business cycles.

Here's a look at consumer confidence levels during the past several decades.

Katona believed that business investment and government policy data were not sufficient in terms of analyzing and understanding the cyclical nature of economics. He used consumer surveys to understand and measure consumer confidence. His point was that the more confidence consumers have in the future, the more they spend. In the U.S., 80% of GDP is consumer spending. Think about it: The less confidence consumers have, the less they will spend. And vice versa. Animal spirits (i.e psychological factors) therefore play a significant role in the direction of the business cycle.

As a practical example in today's environment, here's an excerpt from a recent PIMCO report regarding "animal spirits" in 2017:

"To measure economic optimism and uncertainty, we look at various business and consumer surveys that we've found to be useful leading indicators of inflection points in business cycles. Among the four surveys that have released postelection data, all show a material rise in sentiment, with expected easing of the regulatory and tax burden cited as a specific contributor to the optimism:

> Preliminary results show the December University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index surged 4 percentage points from the prior month, close to a cycle high and reportedly 'largely due to consumers' initial reactions to Trump's surprise victory.' Surveyors went on to say that "more consumers spontaneously mentioned the expected positive impact of new economic policies than ever before recorded in the long history of the surveys."

> The Duke CFO Optimism Index was also up, rising 6 ppts as surveyors indicated that 'CFOs are much more optimistic about the U.S. economy following the election of Donald Trump, particularly with respect to regulatory and tax reform.'

> The Business Roundtable CEO Economic Outlook Index advanced 4.6 ppts as 'America's business leaders are encouraged by President-elect Trump's pledge to boost economic growth.'

> Finally, the NFIB Small Business Optimism Index rose 3.5 ppts to its highest level in over a year. According to NFIB, the November index was basically unchanged from October up to the day of the election and then rose dramatically after the election results were known.

If the upswing in business and consumer confidence surveys persists, it would indicate a likely acceleration in growth--a welcome prospect after the sluggish pace of activity in 2016."

This was written before the start of 2017. If the this year's stock market returns thus far are any indication, investors and advisors should pay attention to what "animal spirits" are saying.

The author is a freelance contributor to Morningstar.com. The views expressed in this article may or may not reflect the views of Morningstar.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/L4B22R7UFVDBJN2ZYJWBSMCIJA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BL6WGG72URAJJJCPC4376SZKX4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZHBXSNJYDNAY7HDFQK47HGBDXY.png)