Performance Fees: An Idea Whose Time Has Come

The current approach to levying fees is outmoded and in need of change.

Executive Summary

- Funds typically levy fees as a fixed percentage of assets under management, but this approach seems outmoded and in need of change.

- Performance-based fees, which vary based on how well a fund performs versus a specified benchmark, could better align fund managers and shareholders.

- While there are arguments against using performance-based fees, they seem to flout market reality and pale when compared with the benefits such fees can yield.

- The forthcoming AB "FlexFee" funds, which would make significant fee adjustments based on fund performance, represent a welcome advance that's worth watching.

An Outmoded System U.S. mutual funds typically levy fees as a fixed percentage of assets. If you're lucky, the board has negotiated some breakpoints with the manager that tier the fees lower as assets increase, but that's usually as good as it gets. For all intents and purposes, investors are paying the same freight for as long as they own a fund, in sickness and in health.

This has meant investors in active funds have typically paid the same fee regardless of how well the funds have done. Crush the benchmark? That’ll be 1% please. Get annihilated? 1%. Perform in line? Well, you get the idea.

That approach seems outmoded and in need of change. Investors are heading in droves to passive funds in large part because they want a fairer shake—that is, to pay fees commensurate with the value they feel they’re receiving. By this standard, active funds aren’t cutting it. And why? Because they charge a premium for a value-add that often fails to materialize.

A Different Approach What to do? Put some skin in the game and reaffirm your alignment with the investor. Vary the fee that's charged depending on whether the fund beats or lags its benchmark. That's how performance-based fees, also known as "fulcrum fees," work. Essentially, the fee gets pushed higher or lower by a predetermined amount based on how well the fund performs versus a specified benchmark index.

As mentioned, very few funds levy performance-based fees, which invites the question why, if this is such a supposedly wonderful idea, hasn’t it caught on? The biggest reason is inertia—fixed fees are a very attractive economic proposition to the asset manager and most don’t want to step off that gravy train. Second, it adds operational and regulatory complexity which many managers detest and, compounding matters, it’s tough to market (“Now with fulcrum fees!”).

(Note: Some academic research has found that performance-based fees haven’t succeeded in improving outcomes. However, the sample sizes have never been large and studies like these are plagued by the effects of other potentially conflating factors.)

But that seems shortsighted for the simple reason that investors seem to be rejecting the status quo in droves, and in the way it overlooks a number of other, less-expected ways performance-based fees could benefit managers and investors alike. Among them are the following.

Less Trading Investors habitually over-transact, and numerous studies have shown they're rarely better off for it. This is as true of portfolio managers as it is of novice investors. Some of this is rooted in emotion and psychology, yes. But it's also partly a matter of optics—to earn his fee, a professional investor reasons that he needs to trade, as that's what the client equates with "active management." A thoughtful, well-constructed performance-based fee, however, can turn that on its head. Instead of trading for the sake of trading, portfolio managers will invest with greater patience and conviction, knowing that their meal ticket depends on the value they add rather than the impression they give off.

Less Index-Hugging Sure, some active-fund managers might continue to ape their benchmarks out of fear, same as today. But a meaningful performance- based fee should nudge them away from the index. If they continued to glom onto the benchmark, they'd generate little outperformance to speak of, and thus have little in fees to show for their effort. Less Bloat If your fee depends on how well you do for the client, not how many shares you're able to sell, that's probably going to make you a lot more finicky about monitoring your fund's capacity. Who wants a bloated fund that's harder to manage if that's going to threaten your future earnings power? Less bloat should mean more sustainable performance, which would be far preferable to the status quo—investors flock to outperformers, the fund company leaves the doors open too long (and why not, as they're levying a flat fee anyway), asset bloat sets in, and returns slip.

Less Product You trade less. You invest with greater conviction. You shut your fund before asset bloat sets in. These are practices that demand resolve, commitment, and pleasure-denial. In other words, it raises the bar, and many active funds, and fund companies for that matter, won't be able to clear it. That might not be such a terrible thing. There are still far too many marginal active funds. A smaller pool of higher-quality funds is better for investors and, therefore, the industry itself over the long term.

Reality Check Performance-based fees are no silver bullet—they're not going to save the active-fund business or investors from themselves. But, directionally, they would push funds in what seems to be the direction of travel—toward alignment and value-for-service. Investors are increasingly dubious about active funds' ability to deliver as advertised and have plenty of potential low-cost substitutes at the ready. Those investors need reassurance, proof really, that active managers are in this together with them. Further, active managers need a mechanism that further encourages them to go their own way, veering from the benchmark and holding the line on trading. Thus, while performance-based fees aren't going to completely arrest the trend toward lower-cost investments or fully dispel doubts about the value of active investing, we should encourage—even applaud—attempts to innovate.

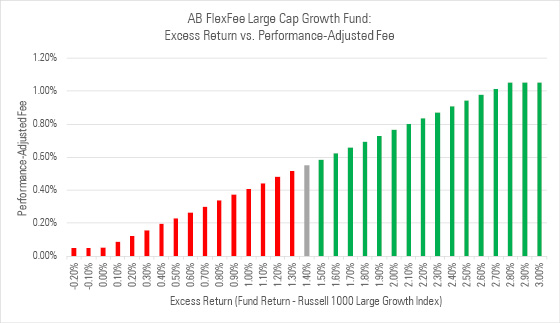

Interesting New Entrant This brings me to the recently launched AB FlexFee family of funds. Though not yet available to the investing public, this suite of six funds registered in late June 2017 and will soon make its formal debut. The funds are interesting in a few ways. For one, it's the first time I can remember a firm branding funds in a way that calls attention to the performance-based fee structure ("FlexFee"). Thus, it appears that AllianceBernstein is attempting to differentiate the funds based on the performance-based fee structure, a milestone of sorts. In addition, the funds' potential performance-fee adjustment is material, not cosmetic. This second point is worth elaborating on a bit, as we've noted a certain, let's call it, lack of gumption among the relatively few funds that levy performance-based fees. Namely, the performance adjustment is insignificant, with most of the fee remaining fixed and a small portion shifting based on performance. In practice, one doubts this type of performance-based fee structure does much to change mindset or behavior, let alone improve outcomes. In that way, the AB FlexFee funds represent a real advance: The performance-fee adjustment has bite. Let's take the forthcoming AB FlexFee Large Cap Growth fund, for example. That fund's "base" management fee is 0.55% per year. However, that fee can go as high as 1.05% or as low as 0.05% depending on how the fund performs over a one-year period versus its benchmark. That benchmark isn't merely a costless index. Rather, it's the Russell 1000 Growth Index plus 1.40%. This means the fund won't earn any upward fee adjustment unless it beats the Russell 1000 Growth Index by 1.40% after all fees and expenses (60 basis points at the fulcrum). . (Technically, the math works as follows: For every basis point that the fund's post-fee returns exceed (or fall shy of) the Russell Index's plus 1.40%, there's a 0.357-basis-point upward (or downward) adjustment of the 0.55% base fee.) What happens if the fund's returns (after any management fees and other expenses) match the Russell 1000 Growth Index's before fees? It won't earn 0.55% but rather 0.05%, the minimum. Why? It lagged its hurdle by 140 basis points (remember, it's not just the Russell Index return but that bogy's return plus 1.40%) and the base fee is reduced by 0.357 basis points for each basis point it lags. Conversely, to earn the maximum 1.05% fee, it must trounce the Russell Index by at least 2.80% before fees. To illustrate, the chart shows the fund's performance-adjusted base fee at various levels of excess returns, with the red bars indicating scenarios where the base fee would be lowered and the green bars those where it would be raised.

- source: Morningstar

Now we wait—not just to see how the funds do, but to see how they're received by investors and, in turn, how other fund companies respond. For now, AllianceBernstein deserves a lot of credit for taking this step (and, yes, I say this knowing that the firm earns most of its fees the old-fashioned way, by levying a fixed percentage fee on the assets it manages). Conclusion The future is likely to continue to test active funds. Performance-based fees, while not a panacea, represent a potentially useful innovation that more funds ought to consider to better align with investors. The launch of the AB funds is an experiment that bears watching, as the firm has taken laudable steps to differentiate the funds by brand and to implement a fee structure that puts a lot of its skin in the game. How investors and competitors respond, time will tell.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FGC25JIKZ5EATCXF265D56SZTE.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/550ce300-3ec1-4055-a24a-ba3a0b7abbdf.png)