When Direct Indexing Truly Pays

The keys are high income and short-term capital gains on Schedule D.

Everyday Shareholders

Direct indexing consists of sampling the stocks of an equity index directly, rather than through a fund. One reason to index directly is to implement shareholder preferences, such as environmental, social, and governance factors. However, as many index funds also incorporate such preferences while being easier to implement, and the expected payoff for indulging one’s personal inclinations is exactly zero, this motivation seems unappealing.

What does interest me is the opportunity for additional profits. These are investments, after all. If established in a taxable account, by an investor who holds another taxable account that generates capital gains, the directly indexed portfolio can be used to create capital losses to offset those gains. The possible result: a lower tax bill for the shareholders, and thus higher aftertax profits. Mission accomplished.

Unfortunately, relatively few taxpayers can prosper from this strategy. Per the IRS Data Book, 89% of taxpayers occupying the $80,000 tax bracket reported no capital gains in the previous year, as did 65% of those in the $300,000 bracket, and even 30% of those who surpassed $1 million. If there are no capital gains for the direct-indexing portfolio to offset, it offers no tax benefit, aside from providing a capital-loss deduction against the first $3000 of income. Own an exchange-traded fund instead.

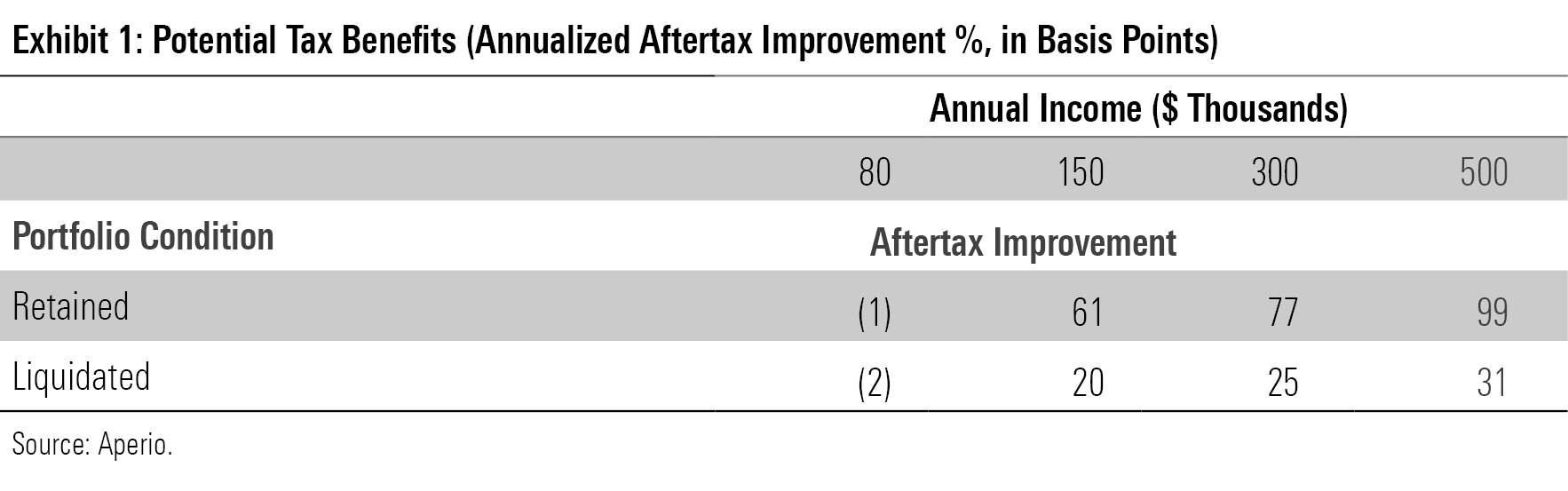

Even among those who earn capital gains, direct indexing often provides few tangible rewards. Friday’s column showed the backtested annualized tax benefit for a married couple holding mutual funds that regularly distribute long-term capital gains.

(This article’s calculations have been supplied by Aperio, a unit of BlackRock BLK. Morningstar has also published on this topic, although its research is only available to financial advisors. For all calculations, when the portfolio is liquidated, the assumed holding period is 10 years.)

Although the numbers initially tempt, they are less enticing after expenses. Because direct-indexing services available to retail investors (from Fidelity and Schwab SCHW) currently cost 35 basis points more per year than the cheapest ETFs, direct indexing provides no net tax advantage for the hypothetical investors profiled in the table once the portfolio is sold. It would help only those who donate or bequeath their assets.

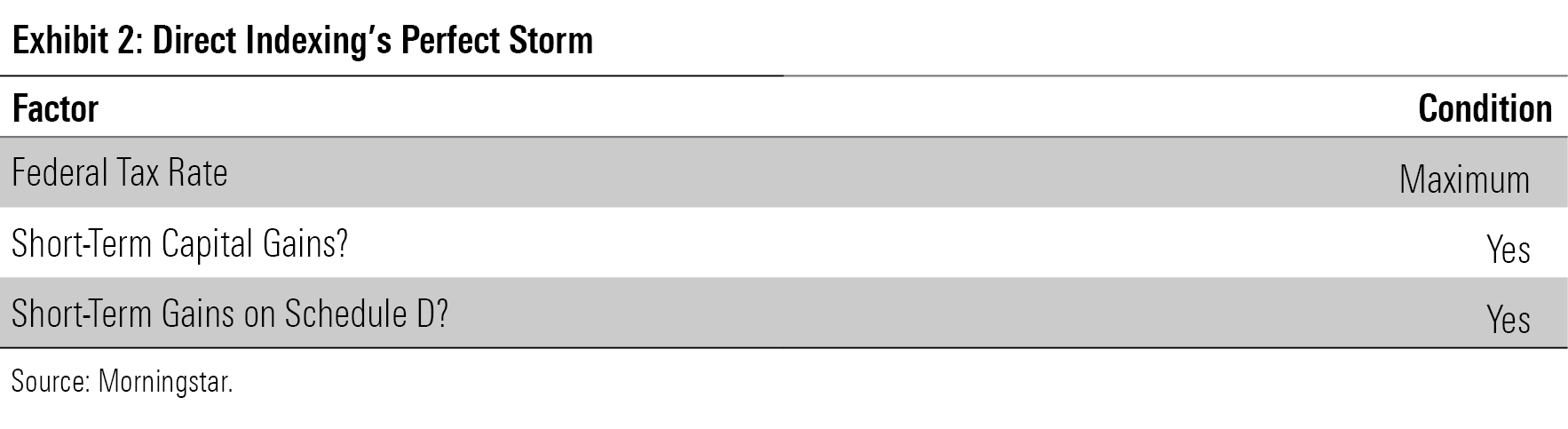

These figures represent the most common outcomes for direct indexing, but the results can be stronger. Indeed, under certain circumstances the strategy becomes so attractive as to almost be irresistible. This occurs under the following three conditions:

A higher tax rate, quite naturally, creates higher taxes, and therefore greater potential tax savings. (Never let it be said that every aspect of this topic is obscure.) Also apparent is that short-term capital gains are more useful to offset than their long-term siblings, as they carry a maximum tax rate of 40.8%, as opposed to the latter’s rate of 23.8%.

Now things get tricky. The IRS treats short-term gains distributed by mutual funds (or other publicly registered funds) as ordinary income, placing them on Form 1090-DIV. After the first $3000 of income, such receipts cannot be offset by capital losses. The same does not apply to realized short-term gains from directly held securities, or distributions made by private investments (such as hedge funds). Appearing on Schedule D forms, such receipts can indeed be erased by capital losses.

In summary, then, the ideal candidates for direct indexing’s tax-management ability are investors who occupy the maximum tax bracket and receive taxable capital gains, some of which 1) are short-term and 2) will appear on their Schedule D report, rather than on Form 1099-DIV. They rest atop the individual-investor pyramid.

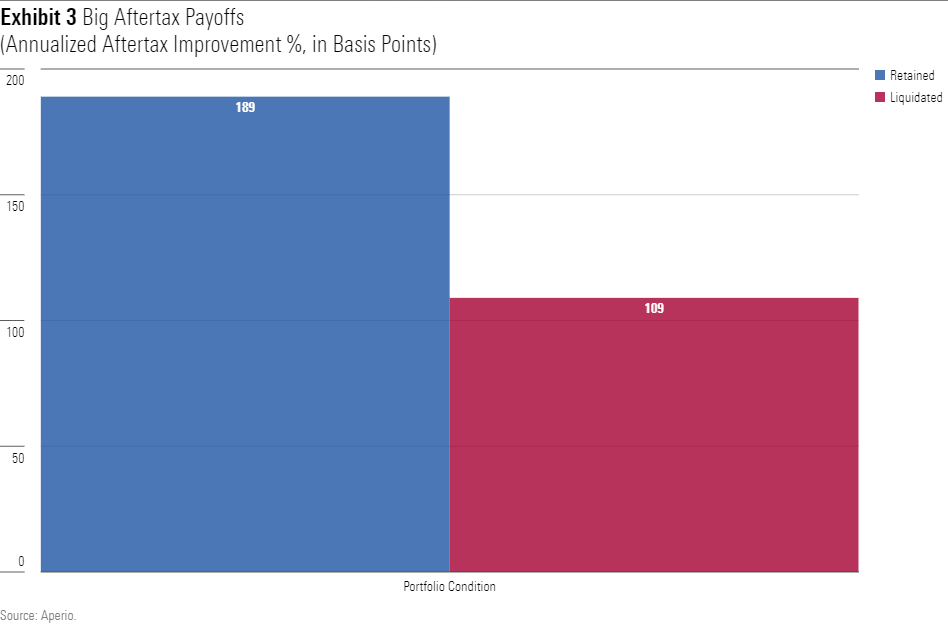

Exhibit 3 shows Aperio’s estimates for such taxpayers, assuming their capital gains are divided evenly between long-term gains and short-term gains, and that the short-term gains appear exclusively on Schedule D.

That’s real money! The amount of tax reduction for high-income investors with Schedule D short-term capital losses can reach almost 2% per year for those who donate or bequeath their portfolios. Admittedly, direct indexing’s tax benefits depend on equities’ fortunes, being highest during volatile markets, when upswings create capital gains and downturns generate capital-loss opportunities. No matter how one shaves that estimate, though, much remains.

With such investors, the post-liquidation outcomes are also favorable. Whereas the mutual-fund investors depicted in Exhibit 1 realized no tax advantage after selling their portfolio and paying direct indexing’s fees, their high-income/Schedule D counterparts benefited from the service even after the portfolio was gone. Erasing a 40.8% tax obligation is no mean feat.

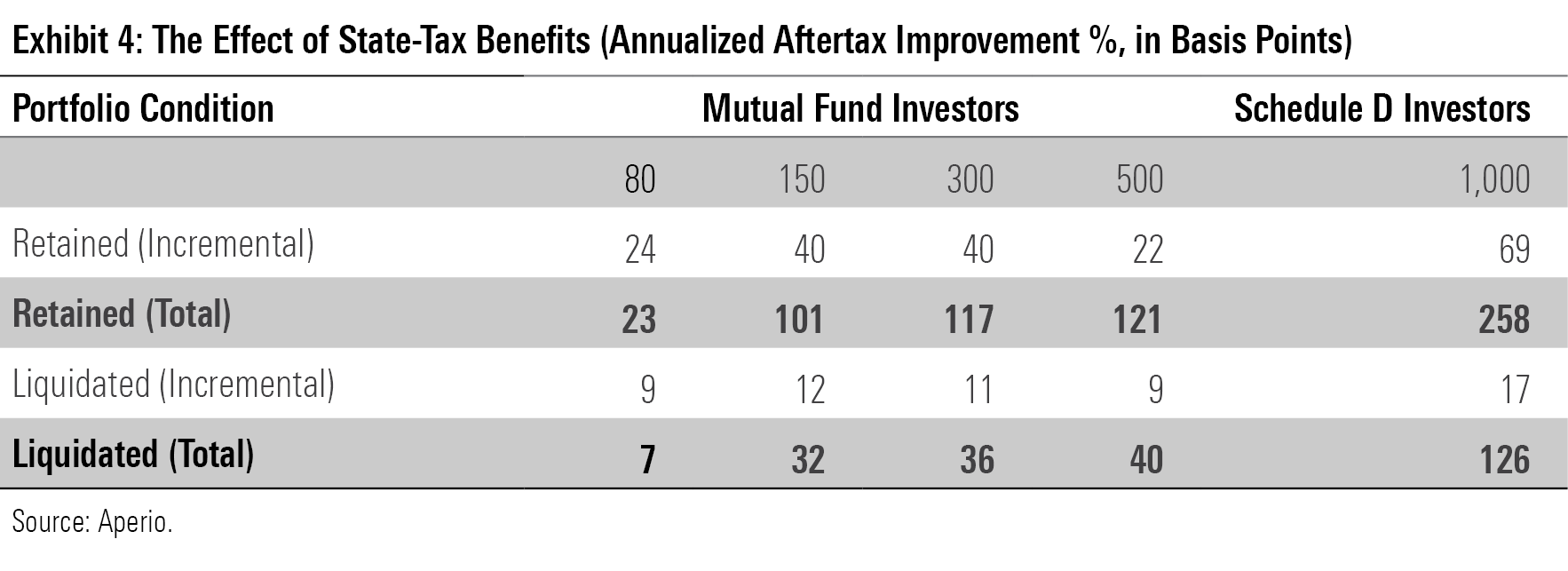

One issue remains: state taxes. Thus far, I have omitted such concerns, to keep the discussion general. But the subject is clearly relevant. Exhibit 4 shows the additional direct-indexing benefit for those who live in high-tax states. For each investor profile, the table provides: 1) the incremental aftertax effect of adding state taxes (Aperio assumed California’s rate); and 2) the bolded total benefit, which includes both federal and state obligations.

The broad lesson remains intact. High state taxes do not change the math for the typical mutual fund investor. Direct indexing does not confer a tax benefit after the extra fees for its service are paid. However, high state taxes make direct indexing even more attractive to those who would already benefit from the strategy: 1) mutual fund shareholders who expected to donate or bequeath their directly indexed portfolios, or 2) high-income investors who report a large amount of short-term capital gains on Schedule D.

Summary

Whew! Although this three-part series on direct indexing covered a lot of ground, much remains uncovered. For example, one reader mentioned another way (aside from its general tax benefit) by which direct indexing can assist with charitable giving; a second worried about direct-indexing portfolios becoming overly concentrated with time, because they harvest their losers and sell their winners; and a third wondered what companies besides Fidelity and Charles Schwab provide retail services. Also, will competitive pressures lead to lower fees?

All in due time. Direct indexing is an intriguing topic, but also complex. My articles are but a part of the educational process (for me, as well as for you, dear reader—when I began this series, I only vaguely knew where the numbers would lead). It will take years for the marketplace to determine whether direct indexing truly offers broad appeal.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZZNBDLNQHFDQ7GTK5NKTVHJYWA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HE2XT5SV5ZBU5MOM6PPYWRIGP4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/AET2BGC3RFCFRD4YOXDBBVVYS4.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)