With Investment Yields, Denominators Also Matter

Not all yield percentages are created equally.

A Free Lunch?

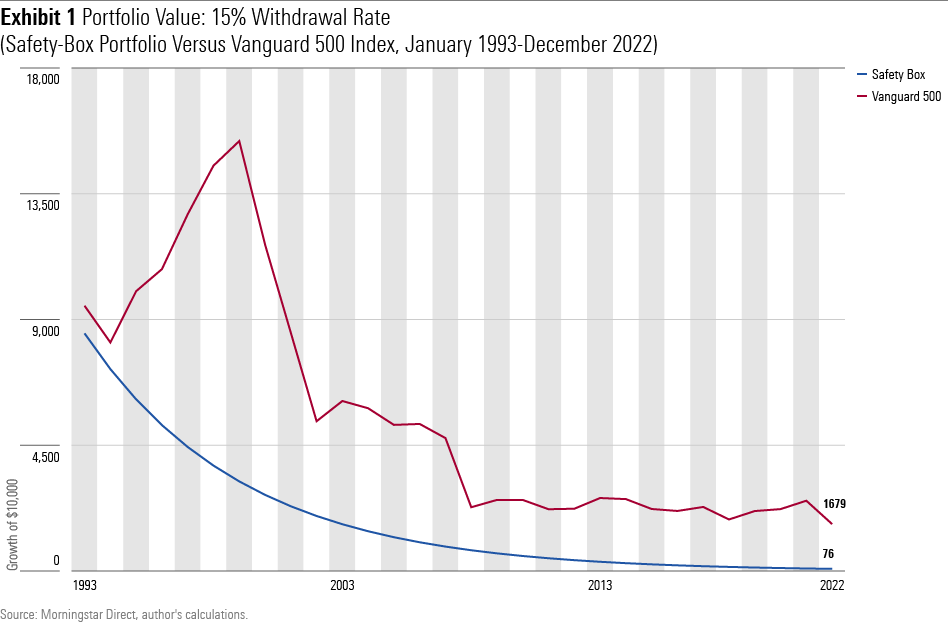

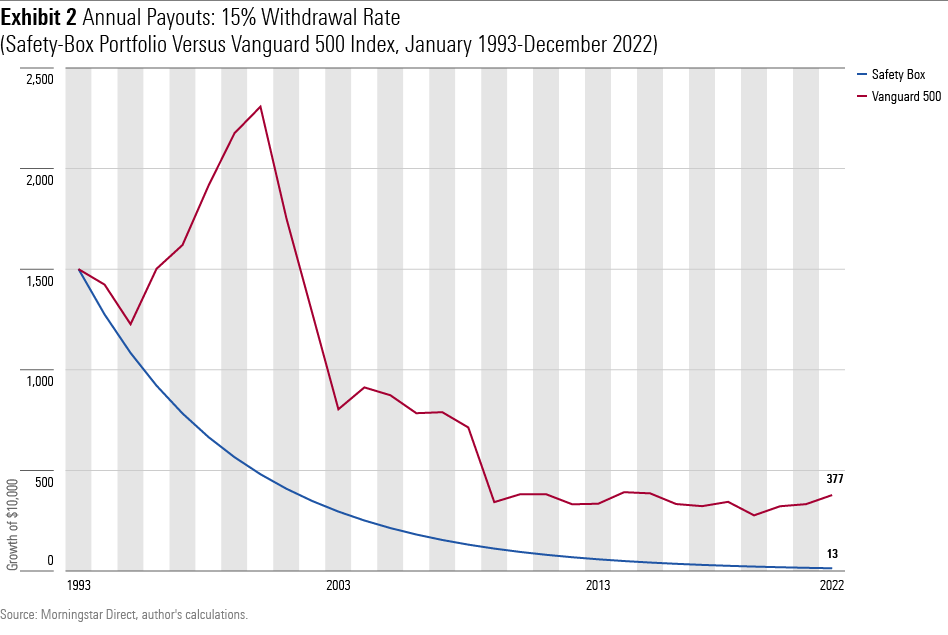

Forget that absurdly conservative 4% withdrawal rule. Retirees can safely remove 15% of their portfolio’s assets every year, for life. You heard it here first.

Not convinced? See for yourself. Moneys stashed in a safe-deposit box can pay 15% per year for three decades without being exhausted. And that is the poor outcome. Investors who withdrew 15% annually from Vanguard 500 Index VFINX from 1993 through 2022 would have finished the 30-year period with 20 times more assets then the safety-box strategy.

Well, all right. The truth emerges. Because portfolios can maintain their withdrawal rates does not mean that they can retain their values. Nor, regrettably, can they retain their payment schedules. A constant withdrawal rate applied to a shrinking asset base equals fewer dollars. Consequently, the chart depicting portfolios’ annual distributions looks much like the “Growth of $10,000″ illustration.

Considering the Denominators

This admittedly silly example—after my three-part slog on direct indexing, this column needs all the humor it can muster—points out an essential truth about investment yields. (Technically, some of the distributions discussed in this column are not “yields,” as they contain capital gains, but the principle holds regardless.) While investors customarily evaluate yield numerators (the higher the better), those amounts only become meaningful after considering the denominators.

Indeed, when the denominator is “the current amount of the portfolio,” the yield percentages are entirely moot. By that measure, all withdrawal rates can be delivered over all time periods. Retirees who located the Fountain of Youth can spend 99.99% of their wealth during each year of the next century. They will eventually die, but their money will survive (assuming the retiree’s financial institution will maintain accounts that are worth only a small fraction of a penny).

Four Categories

Denominators for investment yields—or, if you prefer, retiree-withdrawal rates—place into one of four categories.

1) Declining

Declining denominators pay constant distribution rates, as measured in percentage terms, but ever fewer dollars, owing to the decline in the portfolio’s balance. The latter is sometimes forestalled by an early bull market, but eventually performance reverts. The portfolio’s value falls below its starting point, as does the dollar amount of its cash payments.

Real-life examples: The federal government’s required minimum distribution schedule uses a declining denominator for older investors. Its rate for 85-year-olds is 6.25% (perhaps achievable, for aggressively invested portfolios); its rate for 95-year-olds is 11.24% (not achievable). High-yield bond funds also have declining denominators because they distribute all income they receive rather than withhold assets to defray the capital losses that come from their bonds’ defaults.

2) Flat Nominal

This category is most easily understood. A 4% yield on a $100,000 investment with a flat nominal denominator means a $4,000 annual payout. End of story. For securities that do not face default risk, the analysis concludes. However, while the cash payments avoid nominal decline, they nevertheless fail to keep pace with inflation.

Real-life examples: Treasuries, top-quality municipal bonds, and bank CDs. In theory, investment-grade bond funds also qualify, because their investments make fixed payments and do not default. However, because their portfolios change over time, their payouts also fluctuate. Bond fund denominators are roughly flat nominal, but not precisely so.

Retirement plans relying on fixed payments that are not adjusted for inflation—meaning nominal bonds, annuities, and (largely) private pensions—have flat real denominators. Of course, most would also be leavened with Social Security payments, which operate differently.

3) Flat Real

A flat real denominator grows with inflation. For those accustomed to thinking in nominal terms, the distributions of such securities seem less predictable than those of the second category. For professional investors, though, flat real denominators represent “riskless” yields.

Real-life examples: Few securities aside from Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (and Social Security payments, although the latter of course are not “investments”) explicitly offer flat real denominators. In practice, though, allocation funds often approximate such behavior, thanks to gains from their equities.

Research reports on safe retirement-withdrawal rates, such as Morningstar’s white paper, assume that retiree spending behaves like flat real yields by tracking the rate of inflation. Distributions from retiree portfolios are not true yields because they are supplemented, when necessary, by returns of the investor’s capital. However, the point remains: The percentages given in such reports cannot be usefully compared against either Treasury or annuity rates.

4) Increasing

Increasing yield denominators outstrip inflation, so that the portfolio’s payments grow in real terms. This, obviously, is the happiest scenario.

Real-life examples: Equities. To be sure, they offer no guarantees, but nevertheless, U.S. stocks have provided positive real returns over every 30-year period during the past century. Balanced portfolios also usually manage the task.

Few retirees except the wealthy, who can afford the risk associated with owning stock-heavy portfolios, explicitly target a yield that increases faster than the inflation rate. But such can occur during bull markets, even for those who are relatively conservatively positioned.

Wrapping Up

Percentages can deceive. Dollars do not. For that reason, the fund industry has never much liked the idea of billing shareholders for fund expenses. A $1,000 annual charge on a $250,000 position might raise eyebrows, if the fund has recently lost money. (Few shareholders fuss about the cost of profitable investments.) In contrast, funds that report 0.40% expense ratios, with no dollars attached, will likely go unnoticed.

Investors would do well to take that lesson to heart. In this instance, good business for the fund industry is bad business for investors. When evaluating investment yields—or portfolio spending rates—consider not just the numerator’s percentage, but also the denominator’s effect. Doing so will lead to the only path that truly matters: the dollar trail.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)