I Bonds Are Down, But Not Out

Despite inflation’s decline, they retain several attractive features.

A New Year

Last August, I enthusiastically touted Series I Inflation Bonds, known informally as I bonds. Doing so took no courage, because their 12-month return was largely known. Yields for I bonds are determined in arrears, by using inflation reports that have already been filed. According to the cliché, profitable investments cannot be spotted using a rearview mirror. With I bonds, they can.

Sometimes, I bond earnings can accurately be forecast for an entire year. Owing to the peculiarities of I bonds’ design (when creating them, the Treasury Department showed a sense of humor that one ordinarily does not associate with government bodies), that event occurs twice annually: in late April and then again in late October. That time has now arrived.

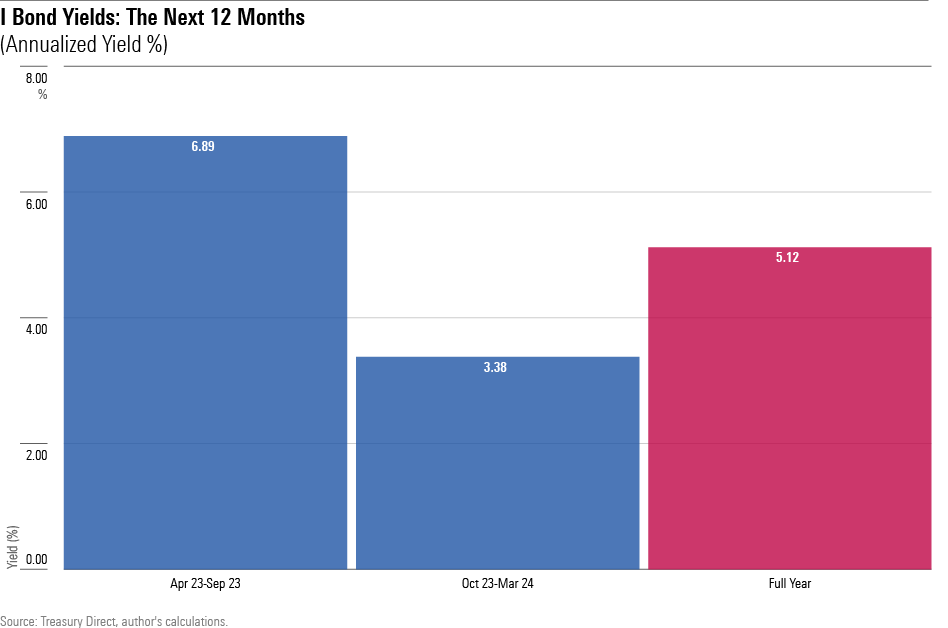

The process works as follows. For the first six months from when it is purchased, which currently means from April 2023 through September 2023, the I bond will pay the inflation rate that occurred one year before, from April 2022 through September 2022. That rate has long been known. In October, the I bond will switch to a newer rate, calculated on inflation’s behavior from October 2022 through March 2023. That information has now become fully public. Voilà!

On the Docket

Here are the numbers. (The full-year amount is very close to the figure that one would get by averaging the two six-month periods, but it is not exactly the same, because of compounding effects.)

This result requires some explanation.

First, those figures overstate the inflation rate. Each time the Treasury adjusts I bond yields, it also considers whether to add a second component to I bonds’ return: an annual fixed yield. Usually the Treasury refrains. Last autumn, however, it included a 0.40% fixed yield. That bonus comes with I bonds that are purchased before May 1, when the current vintage expires. (Whether the new vintage will carry a fixed yield remains to be seen.)

That 40-basis-point bump is permanent: It applies for as long as the shareholder owns the investment. The inflation-based portion of the I bonds’ yield will change along with market conditions, but not the fixed-yield component. Although a modest sum, the sweetener nevertheless is unusual. The last time I bonds paid any fixed yield was in early 2020, and that was an even lower amount: 0.20%.

The other item worth mentioning is that core inflation hasn’t dropped as much as the chart suggests. Earnings on I bonds are derived from the unadjusted version of the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, or CPI-U, which includes the fluctuating effects of food and energy. The latter soared last summer but has since declined by 8.1%. Good news for consumers, but bad news for I bond returns.

Recent History

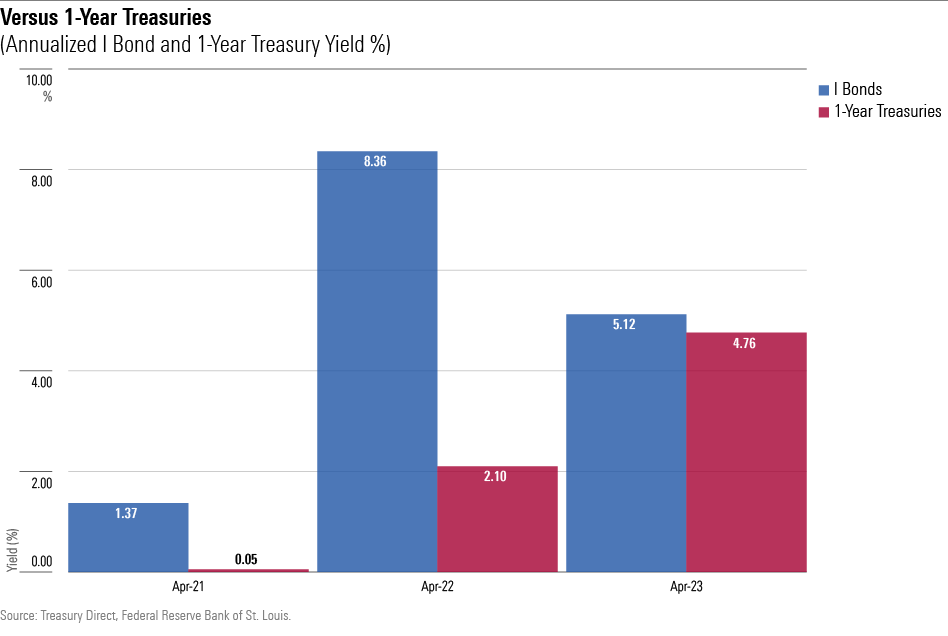

Let’s compare today’s outlook against those of the previous two years. The following chart shows the 12-month returns received by investors who bought I bonds on April 30 of 2021 and 2022, along with the prospective returns (taken from the previous exhibit) for those who purchased today. Also depicted are the prevailing yields on one-year Treasury notes, to appreciate the investment competition.

The picture is very clear. I bonds made nobody wealthy in 2021, but they easily beat the short-term alternative. One year later, their prospective 12-month returns were healthy by any standards—and outstanding compared with government-backed securities. Today, their near-term appeal is less obvious. Over the next year, I bonds will only slightly outgain one-year Treasuries.

Should investors wish to book their profits after those 12 months have passed, Treasury notes would lead, because investors who redeem I bonds within five years of their purchase date must forgo three months’ worth of interest. (After 30 years, I bonds automatically redeem.) The interest penalty did not matter for the previous two years’ analysis; then, I bonds were superior regardless. But not this time around.

Further Considerations

That said, there remain several valid arguments for buying I bonds from now until the month ends.

First, they offer those 40 basis points of fixed yield. Although that amount trails the average postinflation return of conventional Treasuries, the latter’s results are uncertain. Should inflation over the next decade surpass the 3.51% yield now provided by 10-year Treasuries, I bonds will be superior.

As former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers mused at this week’s Morningstar Investment Conference, while optimists believe the Federal Reserve will successfully put inflation back in its bottle, can anybody claim with complete confidence that inflation will not exceed 4% over the next decade? Surely not.

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities are a stronger I bond alternative. Because it, too, provides returns that are directly linked to the unadjusted version of the CPI-U statistic, along with a substantially higher real yield than is offered by I bonds, a 10-year TIPS that is held to maturity will reliably outgain today’s I bond. As evidenced by last year’s steep losses, though, TIPS are risky for those who might need to sell along the way.

Also, whereas I-bond investors may choose to retain their holdings when the decade concludes, TIPS investors cannot. They must accept the Treasury Department’s payment and redeem their shares. Which means that if they reinvest, they might be forced to accept lower yields than what I bonds now deliver. That is a realistic possibility; during three of the past 12 years, real yields on 10-year TIPS have been negative.

Summary

I bonds are an imperfect investment. They are available only through the Treasury itself, and then in limited quantities. (The maximum permitted amount is $10,000 each year for individuals, or $15,000 if buying with a federal tax refund.) And with inflation waning, they are clearly less appealing than when I discussed them last summer. However, they remain a viable investment option for those seeking safe, inflation-protected performance.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)